Space agriculture boldly grows food where no one has grown before

As access to space increases, the potential for terrestrial benefits directly tied to space exploration grows exponentially.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Ajwal Dsouza, PhD Candidate, Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph

Thomas Graham, Assistant Professor, Environmental Sciences, University of Guelph

Whether to spend money on outer space exploration or to apply it to solve serious problems on Earth, like climate change and food shortages, is a contentious debate. But one argument in favor of space exploration highlights benefits that do, in fact, help study, monitor and address serious concerns like climate change and food production.

As access to space increases, the potential for terrestrial benefits directly tied to space exploration grows exponentially.

For example, agriculture has been improved significantly through the application of space-based advances to terrestrial challenges. It is now increasingly likely that food items have been produced with the assistance of space-based technologies, like freeze-dried foods, or through the use of crop monitoring from space-based observatories.

Related: Astronauts enjoy space veggies and look to the future of cosmic salads

Monitoring farmlands

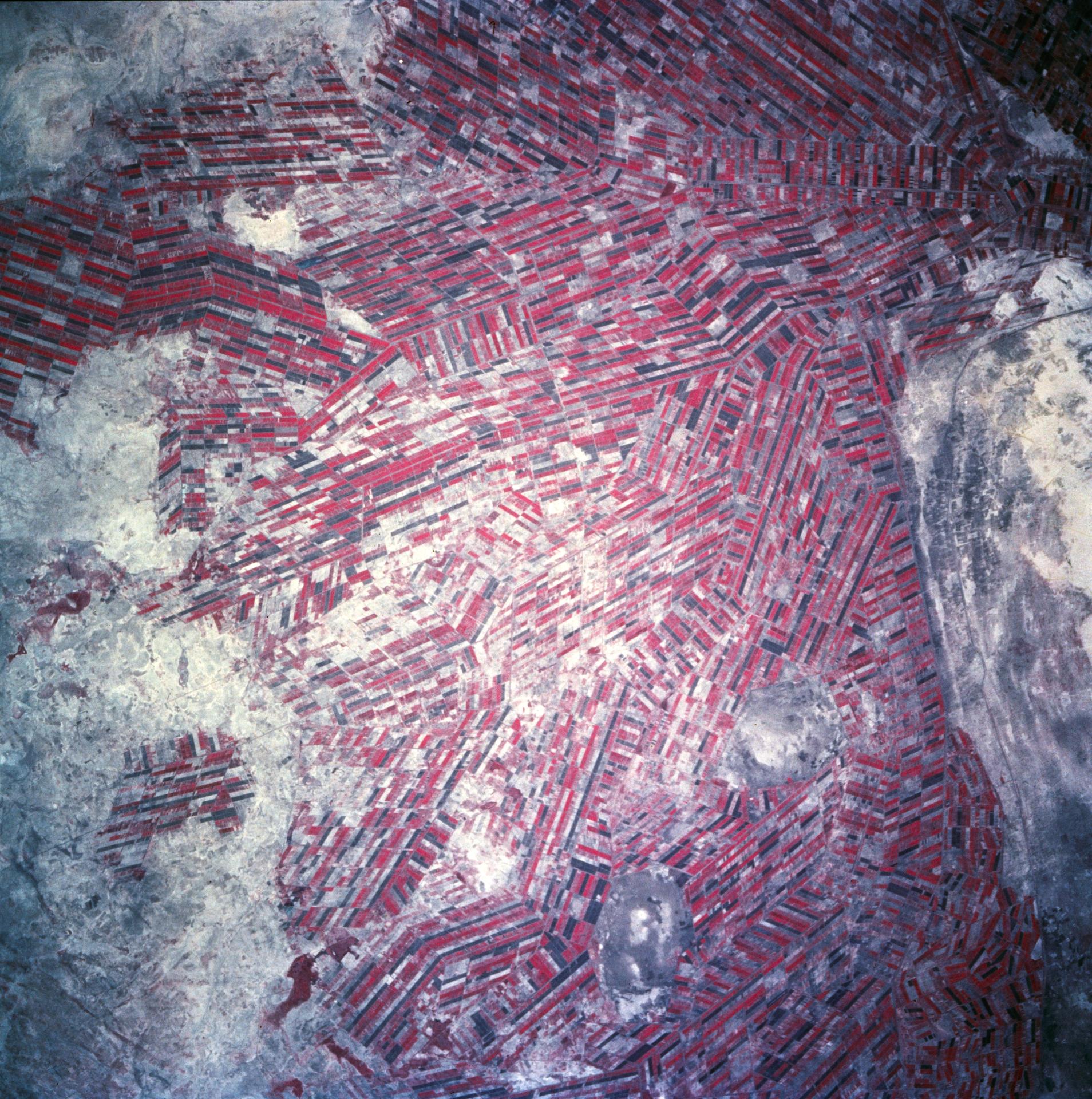

Satellite monitoring is arguably the most realized benefit of space for farming. Like mindful eyes in the sky, satellites watch over the farmlands across the globe day and night. Specialized sensors on relevant satellites (for example, NASA's Landsat, the European Space Agency's Envisat and the Canadian Space Agency's RADARSAT) monitor various parameters relevant to agriculture.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Sensors monitoring soil moisture can tell us when and how fast soils are drying, helping direct more efficient irrigation on a regional scale. Weather satellites help predict drought, floods, precipitation patterns and plant disease outbreaks.

Satellite data helps us predict food insecurity threats or crop failures.

Plant science

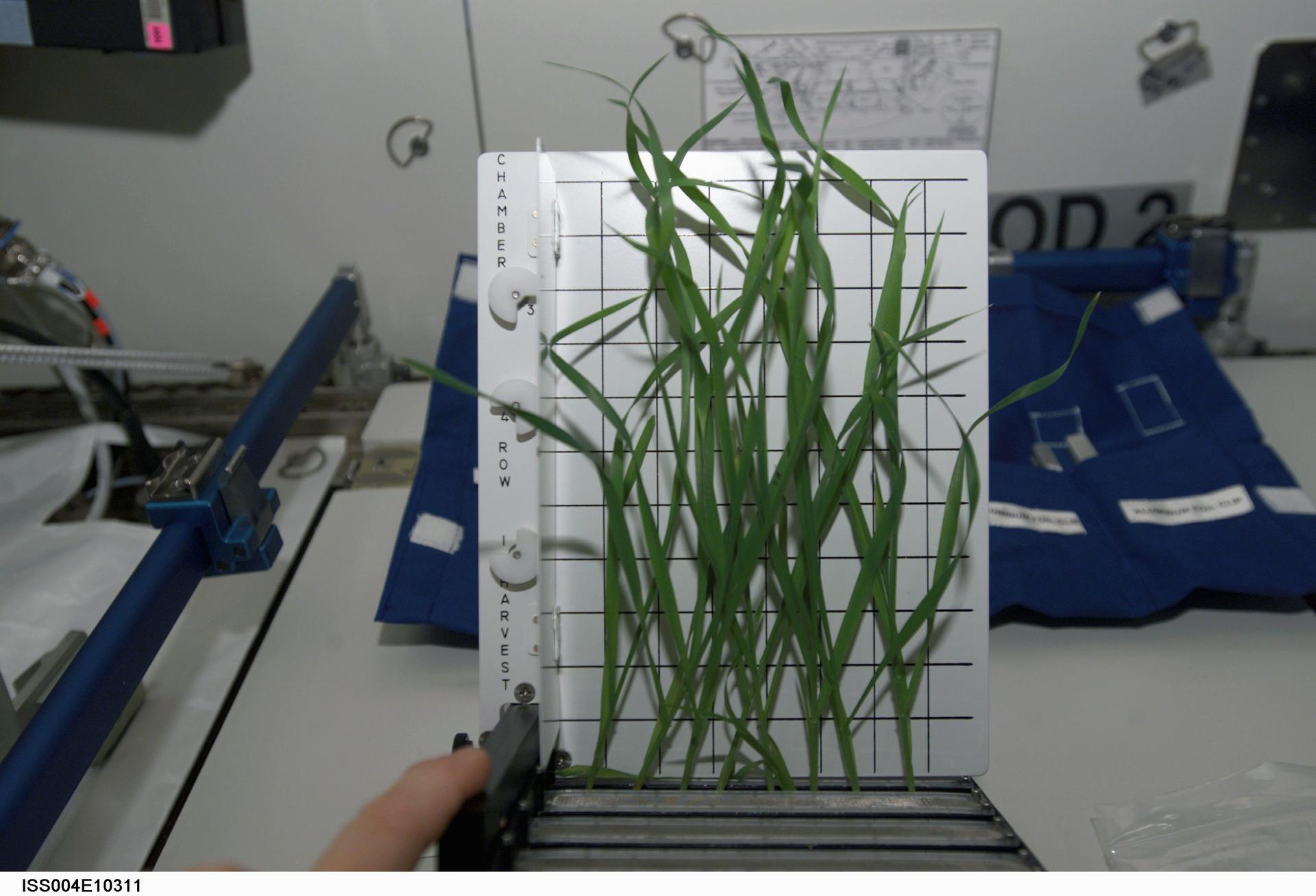

It's not only lifeless machines that dwell in space. Humans have managed to survive and grow plants in low-Earth orbit aboard several spacecraft and stations. Space is the ultimate "harsh environment" for life to exist in, including plants, due to such novel stressors as cosmic radiation and lack of gravity.

Space biologist Anna-Lisa Paul describes plants as being able to "reach into their genetic toolbox and remake the tools they need" to adapt to the novel environment of space. The new tools and behaviors expressed by plants under spaceflight conditions could be used to solve challenges facing crops in Earth's changing climate.

Researchers at NASA sent cotton seeds to the International Space Station to understand how cotton roots grow in the absence of gravity. The findings of the research will help develop cotton plant varieties with a deeper root system to access and absorb water more efficiently from soil in drought-prone areas.

Farming technologies

Soon, humans will go to the moon and eventually to Mars. While there, astronauts will have to grow their own food.

Space agencies have been working on specialized systems that provide the conditions necessary for plant cultivation in space. These systems are containers that can control the internal environment and grow plants without soil under LED lights. NASA's research in controlled environment systems to grow plants was foundational in developing the modern-day vertical farm sector — indoor farms that grow crops in stacks without soil under the purple haze of LEDs.

Now a burgeoning industry, vertical farms are churning out enormous volumes of fresh and healthy leafy crops with a fraction of the water and nutrients that would be used in land-based farm systems. Vertical farms can be set up within cities, right where the demand lies, thereby cutting the need for long-distance transport.

As crops are grown indoors in controlled environments, vertical farms can substantially reduce the reliance on herbicides and pesticides, while recycling water and preventing nutrient runoff.

Space agriculture, Earth benefits

Considering the constraints of space, crop production techniques need to be more energy-efficient and require minimal human input. Crops need to also be nutrition-rich, with the ability to withstand high-stress environments. These features are also desirable for crops on Earth.

Scientists are developing a more resource-efficient potato crop where the whole plant can be consumed, including roots, shoots and fruits. Such crops will play a pivotal role in addressing food and nutritional security on Earth and in space.

Space exploration has served as a major driver for technological advances. The renewed interest in space can only benefit agriculture here on Earth by providing new opportunities to improve agriculture. Innovations that are quite literally out of this world can provide us tools to tackle food production under the looming threats posed by global climate change.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Passionate about growing plants in soil, cities, and space. PhD Graduate student at the University of Guelph, Canada.