NASA faces tough decisions on Orion capsule's heat shield for Artemis moon missions

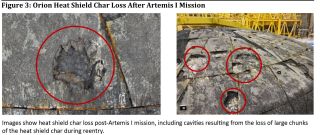

NASA identified more than 100 locations where ablative thermal protective material was liberated during its speedy reentry.

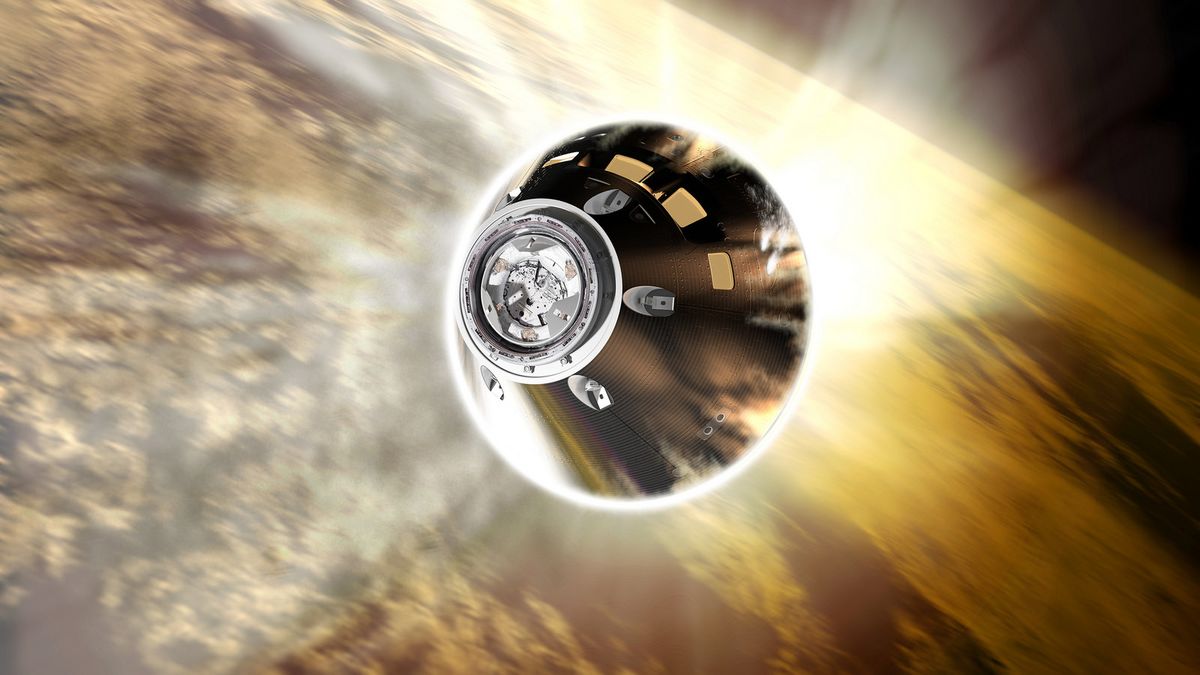

NASA remains in an ongoing test mode to determine what's behind the ablative thermal protective material that chipped away unexpectedly from the Artemis 1 Orion heat shield during its reentry into Earth’s atmosphere back on Dec. 11, 2022.

The Orion spacecraft for the Artemis 1 mission splashed down in the Pacific Ocean after a 25.5-day mission.

During the high-speed, 25,000 miles per hour return from lunar distance, the thermal protection system of Orion’s crew module must endure blistering temperatures to keep crew members safe. Measuring 16.5 feet in diameter, Orion's heat shield is the largest of its kind developed for missions carrying astronauts.

Root cause

But in a post-flight analysis of the Artemis 1 heat shield, NASA identified more than 100 locations where ablative thermal protective material was liberated during its speedy reentry.

Work to determine the root cause did conclude last summer, said NASA’s Lori Glaze Deputy Associate Administrator (Acting) Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate.

Speaking Oct. 29 at the Annual Meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group being held in Houston, Texas, Glaze did not say what root cause was uncovered.

However, Glaze said that additional testing is ongoing before any final determination is made. That testing will conclude by the end of November, then provided to NASA chief, Bill Nelson, for a final decision.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Artemis II

Meanwhile, NASA is moving forward on readying the Artemis 2 hardware to support hurling a four-person crew to sojourn out beyond the moon, then return to Earth.

The Artemis 2 crew is to depart Earth no earlier than September 2025 on a 10-day trek.

In classic "wait a minute" style, a NASA Office of Inspector General (OIG) report was issued in May of this year – "NASA’s Readiness for the Artemis II Crewed Mission to Lunar Orbit" – calling attention to this issue and others before sending off the first human crew toward the moon since 1972 – the Apollo 17 mission.

To ensure the safety of the crewed Artemis 2 mission, the OIG report recommended the Associate Administrator for Exploration Systems Development Mission Directorate to ensure the root cause of Orion heat shield char liberation is well understood prior to launch of the Artemis 2 mission.

The OIG report called for analysis of Orion separation bolts using updated models that account for char loss, design modifications, and operational changes to Orion prior to the Artemis 2 launch.

The report by the NASA OIG also notes that "human spaceflight by its very nature is inherently risky, and the Artemis campaign is no exception. We urge NASA leadership to continue balancing the achievement of its mission objectives and schedule with prioritizing the safety of its astronauts and to take the time needed to avoid any undue risk."

Avcoat changes

The heat shield features the same ablative material called Avcoat used in Apollo lunar outings and return-to-Earth missions. However, the building process has changed, according to Lockheed Martin that fashioned Orion’s thermal protection system.

"Instead of having workers fill 300,000 honeycomb cells one by one with ablative material, then heat-cure the material and machine it to the proper shape, the team now manufactures Avcoat blocks – just fewer than 200 – that are pre-machined to fit into their positions and bonded in place on the heat shield’s carbon fiber skin," the aerospace firm’s website explains. That process is a timesaver in putting on the Avcoat – about a quarter of the time.

So here's the lingering and nagging question: Is it possible that changes in the Avcoat may be needed? If so, that decision would seemingly necessitate de-coupling the heat shield from the Artemis 2 Orion capsule.

Heat shield hiccups

When the heat shield issue first came to light, Space.com contacted the Orion program office at NASA Johnson Space Center for comment regarding the heat shield hiccups.

"During Artemis 1 post-flight inspection, engineers observed variations of Avcoat material across the appearance of Orion's heat shield. Some areas of expected charred material ablated away differently than computer modeling and ground testing predicted, and there was slightly more liberation of the charred material during re-entry than anticipated," the program office stated.

"We expect the material to ablate with the 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit the spacecraft encounters on a re-entry through Earth's atmosphere, and to see charring of the material through a chemical reaction, but we didn’t expect the small pieces that came off, versus being ablated," the NASA statements adds.

Healthy margin

"We don’t know yet exactly how much was liberated, which is why we’re analyzing the data, but there was a healthy margin remaining of virgin Avcoat, and temperature data inside the cabin remained at expected levels, so if crew were on board they would not have been in danger," explains the program office statement.

"It's still too early in our testing and analysis to arrive at any potential recommendations or solutions that address additional char liberation," NASA responded. "It's possible the phenomenon may just [be] part of what the heat shield is, and what we would expect as we return from the moon, but we'll let the data inform us."

Lastly, the NASA Orion program office stated: "We'll continue to protect for variations that could happen during re-entry as we want to ensure we have significant margin against the various types of uncertainties that might occur as the spacecraft re-enters the atmosphere. Our teams want the confidence that we have the best heat shield possible to fly humans going forward."

In double-checking with the NASA Orion program office, Space.com was advised "we have not made any decisions yet, but NASA will provide an update on our plans after the completion of the investigation, and we have determined a forward path."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

-

Unclear Engineer I hope NASA has learned its lesson regrading the need to positively deal with small early indications of things that might become much larger issues - such as solid fuel rocket booster seal leaks and ice patches falling of the exteriors of propellant tanks and hitting vital reentry craft surfaces.Reply

If you don't understand why it is happening, then you really do not understand how bad it can get. -

Dakota53 Reply

Agree 100% - 300,000 individual honeycomb pieces sounds a lot more robust that 200 sectional pieces. Since we have had a tragedy in this area already with Columbia, one would hope the why, the how, and the fix is 100%Unclear Engineer said:I hope NASA has learned its lesson regrading the need to positively deal with small early indications of things that might become much larger issues - such as solid fuel rocket booster seal leaks and ice patches falling of the exteriors of propellant tanks and hitting vital reentry craft surfaces.

If you don't understand why it is happening, then you really do not understand how bad it can get. -

palmerfralick you have to wonder with all the the new testing and analyzing of what went wrong with the current heat shield that if in the end they will waste more time and money than they would have if they had used the obviously successful Apollo 300K honeycomb method to begin with. If it aint brokeReply

why try to make it cheaper? -

ultimatewizz Another problem with a product made by Boeing. They should not be allowed to make any thing for the space program, PERIOD. What is it going to take for NASA to dump them.Reply -

ultimatewizz Reply

Haven't heard one complaint about anything SpaceX is sending up and bring back. Hmmm.palmerfralick said:you have to wonder with all the the new testing and analyzing of what went wrong with the current heat shield that if in the end they will waste more time and money than they would have if they had used the obviously successful Apollo 300K honeycomb method to begin with. If it aint broke

why try to make it cheaper? -

Unclear Engineer I think the reason for the separately applied tiles is for reusability of the capsules.Reply -

ultimatewizz Reply

Doesn't matter, Boeing is a disaster and SpaceX reuses booster and capsules and I believe they know more and find and fix their problems far quicker than Boeing. Musk has a good team in Texas.Unclear Engineer said:I think the reason for the separately applied tiles is for re usability of the capsules.