Meteorites and asteroids tracked back to their place of origin in the solar system

"This has been a decade-long detective story, with each recorded meteorite fall providing a new clue."

Ten years ago, astronomers from various institutions, including NASA and SETI (Search for ExtraTerrestrial Intelligence), set out to map the asteroid belt by tracking meteorites as they blazed through Earth’s atmosphere.

To do this, they built a network of all-sky cameras across the globe, which they named the Global Fireball Observatory.

"This has been a decade-long detective story, with each recorded meteorite fall providing a new clue," one of the project’s founders, Peter Jenniskens of the SETI Institute and NASA Ames Research Center, said in a statement. "We now have the first outlines of a geologic map of the asteroid belt."

Jennisken’s colleague, Hadrien Devillepoix of Curtin University, added: "Others built similar networks spread around the globe, which together form the Global Fireball Observatory. Over the years, we have tracked the path of 17 recovered meteorite falls."

The team's research was published on Monday (March 17) in the journal Meteoritics & Planetary Science.

From the main asteroid belt to Earth's atmosphere

Meteorites are rocks from space that survive their fiery descent through Earth's atmosphere and reach the ground. More than just dazzling streaks of light as meteors, these ancient fragments are among the oldest materials in our solar system, originating from planets, asteroids, and comets.

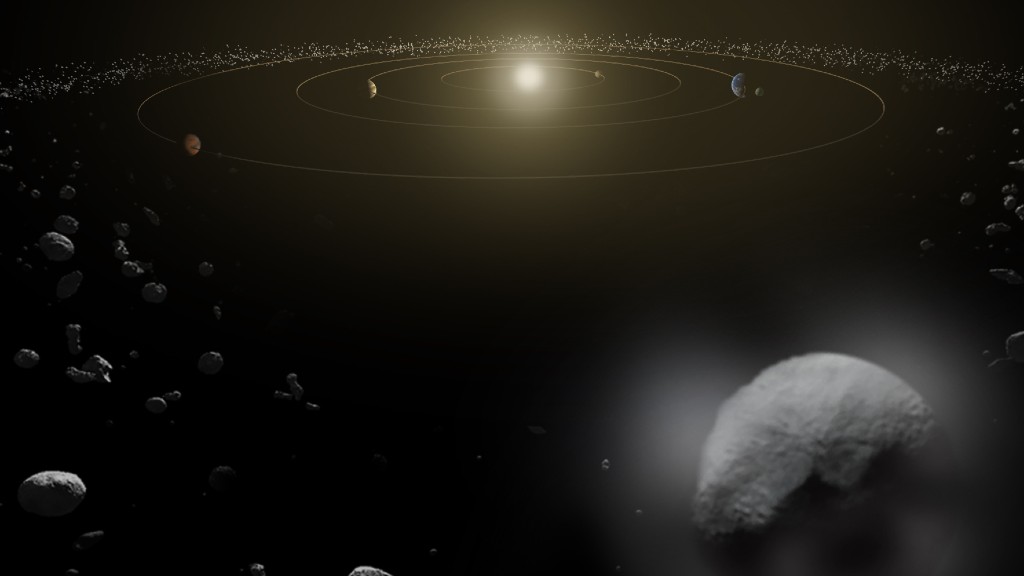

Most meteorites, however, originate from the solar system's main asteroid belt—a vast region between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter where more than a million asteroids circle the sun. Its formation remains a subject of debate, but astronomers believe it dates back around 4.5 billion years to the formation of the solar system's planets. These asteroids are thought to consist of leftover planetesimals, the building blocks of planets that never fully coalesced into a larger body.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The asteroid belt contains debris fields known as clusters, which form when larger asteroids break apart due to random collisions. These smaller fragments remain grouped together and are called asteroid families.

By measuring the radioactive elements present in a meteorite, astronomers can determine their age and match it to the "dynamical age" of asteroid debris fields. The dynamical age is the amount of time that has passed since an asteroid or group of asteroids was disrupted or scattered, determined by studying how the objects have spread out over time due to their movements and interactions, like gravitational forces or collisions.

The more spread out the asteroids are, the older the debris field is likely to be. Essentially, it gives an estimate of how long it has been since the original disruption that caused the objects to scatter.

By analyzing data gathered from watching the night sky and by using a combination of video footage and photographic observations of meteors, Devillepoix, Jenniskens, and their teams have tracked the origins of 75 meteorites in the asteroid belt.

"Six years ago, there were just hints that different meteorite types arrived on different orbits, but now, the number of orbits (N) is high enough for distinct patterns to emerge," they wrote in their paper.

One particularly interesting finding centers around iron-rich ordinary chondrite meteorites or "H chondrites," one of the most common types of meteorites that land on Earth. Their chemistry is considered primitive because they have never undergone melting and have experienced very few chemical interactions since their formation—making them valuable time capsules for understanding the early solar system.

"We now see that 12 of the iron-rich ordinary chondrite meteorites (H chondrites) originated from a debris field called 'Koronis,' which is located low in the pristine main belt," said Jenniskens. "These meteorites arrived from low-inclined orbits with orbital periods consistent with this debris field.

"By measuring the cosmic ray exposure age of meteorites, we can determine that three of these twelve meteorites originated from the Karin cluster in Koronis, which has a dynamical age of 5.8 million years, and two came from the Koronis2 cluster, with a dynamical age of 10-15 million years," he continued. “One other meteorite may well measure the age of the Koronis3 cluster: about 83 million years.”

The team also discovered that several groups of meteorites, including H-chondrites, originated from different regions in the asteroid belt. Some H-chondrites, with an age of about 6 million years, come from the Nele asteroid family, while others, with an exposure age of 35 million years, come from the inner main belt, likely from the Massalia asteroid family.

They also found that the second most common group of meteorites, stony L chondrites, and the least abundant stony meteorites, LL chondrites, which are primarily from the inner main belt, trace back to the Flora and Hertha asteroid families. The L chondrites, in particular, experienced a violent origin 468 million years ago and are linked to a massive collision.

While this provides one of the most comprehensive maps of the asteroid belt to date, not all meteorites in the database were assigned, and some assignments still carried uncertainty.

But for Devillepoix and Jenniskens, this is just the beginning.

"We are proud about how far we have come, but there is a long way to go," said Jenniskens. "Like the first cartographers who traced the outline of Australia, our map reveals a continent of discoveries still ahead when more meteorite falls are recorded.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.