How much did SpaceX's Starship Flight 7 explosion pollute the atmosphere?

Scientists are not sure how much metallic dust remained in the atmosphere after the most recent SpaceX rocket 'disassembly.'

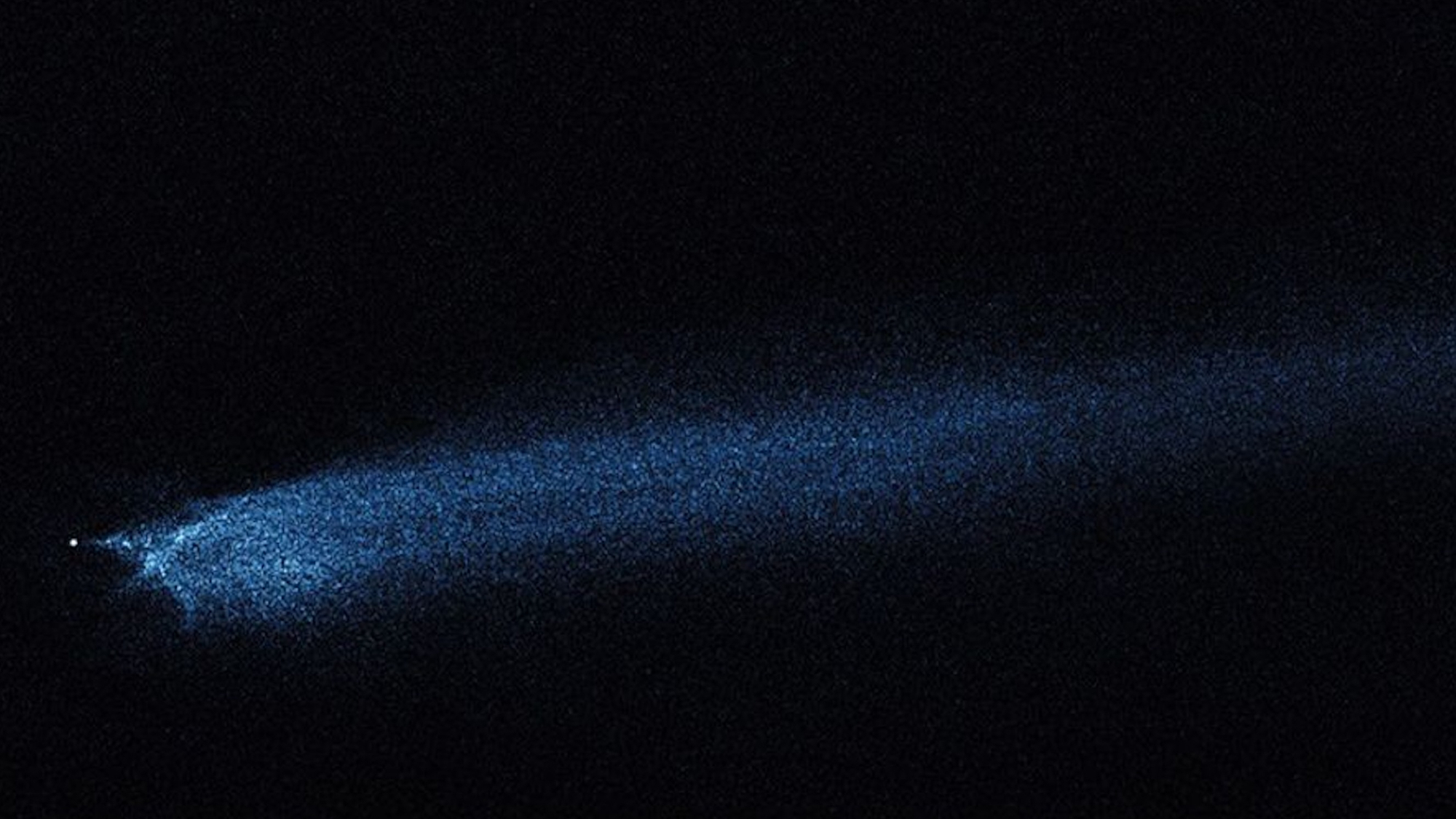

The rapid unscheduled disassembly (aka explosion) of SpaceX's Starship megarocket that rained scorching fragments of metal across the Caribbean in mid-January may have released significant amounts of harmful air-pollution into the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere.

The rocket's upper stage blew up at an altitude of around 90 miles (146 kilometers) according to astronomer and space debris expert Jonathan McDowell, and weighed some 85 tons without propellant. Its plunge back to Earth through the atmosphere may have generated 45.5 metric tons of metal oxides and 40 metric tons of nitrogen oxides, according to University College London atmospheric chemistry researcher Connor Barker. Nitrogen oxides in particular are known for their potential to damage Earth's protective ozone layer.

Barker, who had recently published an inventory of rocket emissions and pollutants from satellite re-entries in the journal Nature, posted the estimates on his LinkedIn profile shortly after the mishap. He, however, stressed in an email to Space.com that the numbers are a rough, preliminary estimate rather than an accurate calculation of the accident's environmental impact.

In Barker's LinkedIn post, however, the scientist said that the amount of metallic air pollution potentially produced in the accident equals that generated by one third of meteorite material that burns up in Earth's atmosphere every year.

Exactly how much pollution the Starship mishap produced in the higher atmosphere is hard to tell. Scientists, for example, are also not sure how much of the megarocket's mass burned up and how much of it fell to Earth.

McDowell told Space.com that "many tons" likely splashed down into the ocean.

Fortunately, the Starship upper stage is made of stainless steel and not aluminum like satellites and upper stages of many other rockets including SpaceX's Falcon 9. The incineration of aluminum is what worries many scientists. When aluminum burns at high temperatures during a satellite re-entry, it produces aluminum oxides, or alumina, a white powdery substance known for its potential to damage ozone and change the reflectiveness of Earth's atmosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

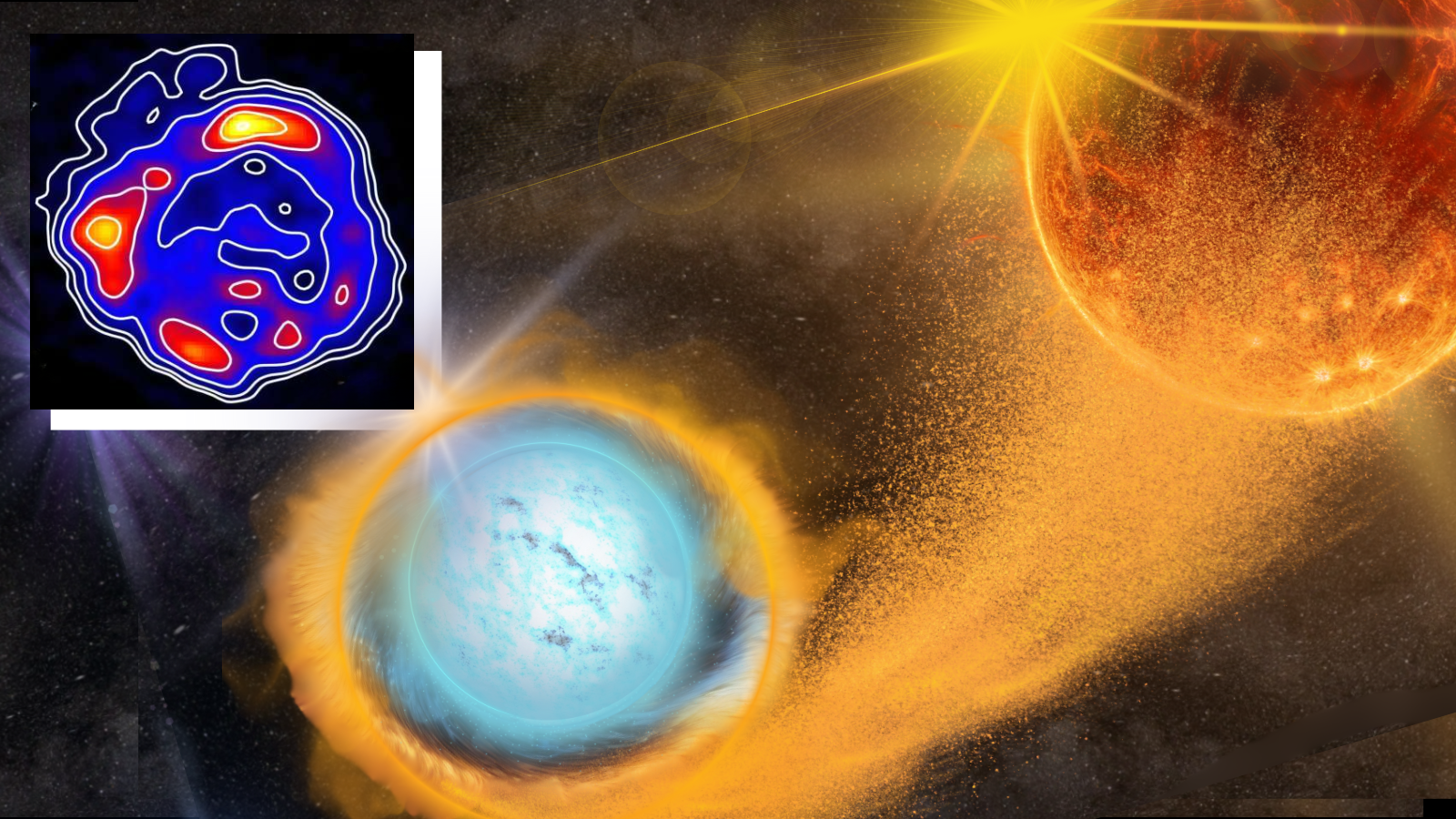

In recent years, the number of satellites orbiting Earth and that of subsequent atmospheric re-entries has been rising fast. With that the amount of alumina released into the mesosphere and upper stratosphere — the otherwise pristine middle layers of the atmosphere — has been skyrocketing. Air pollution in the mesosphere and upper stratosphere concerns scientists as the high altitudes at which it arises mean the pollutants remain in the air for a very long time.

Scientists think that the quantity of alumina from incinerated satellites is already approaching the same levels that result from the atmospheric demise of natural space rocks such as asteroids or meteoroids, which contain only trace amounts of aluminum. The amount of nitrogen oxides produced during re-entries is also nearing that generated by natural space rocks.

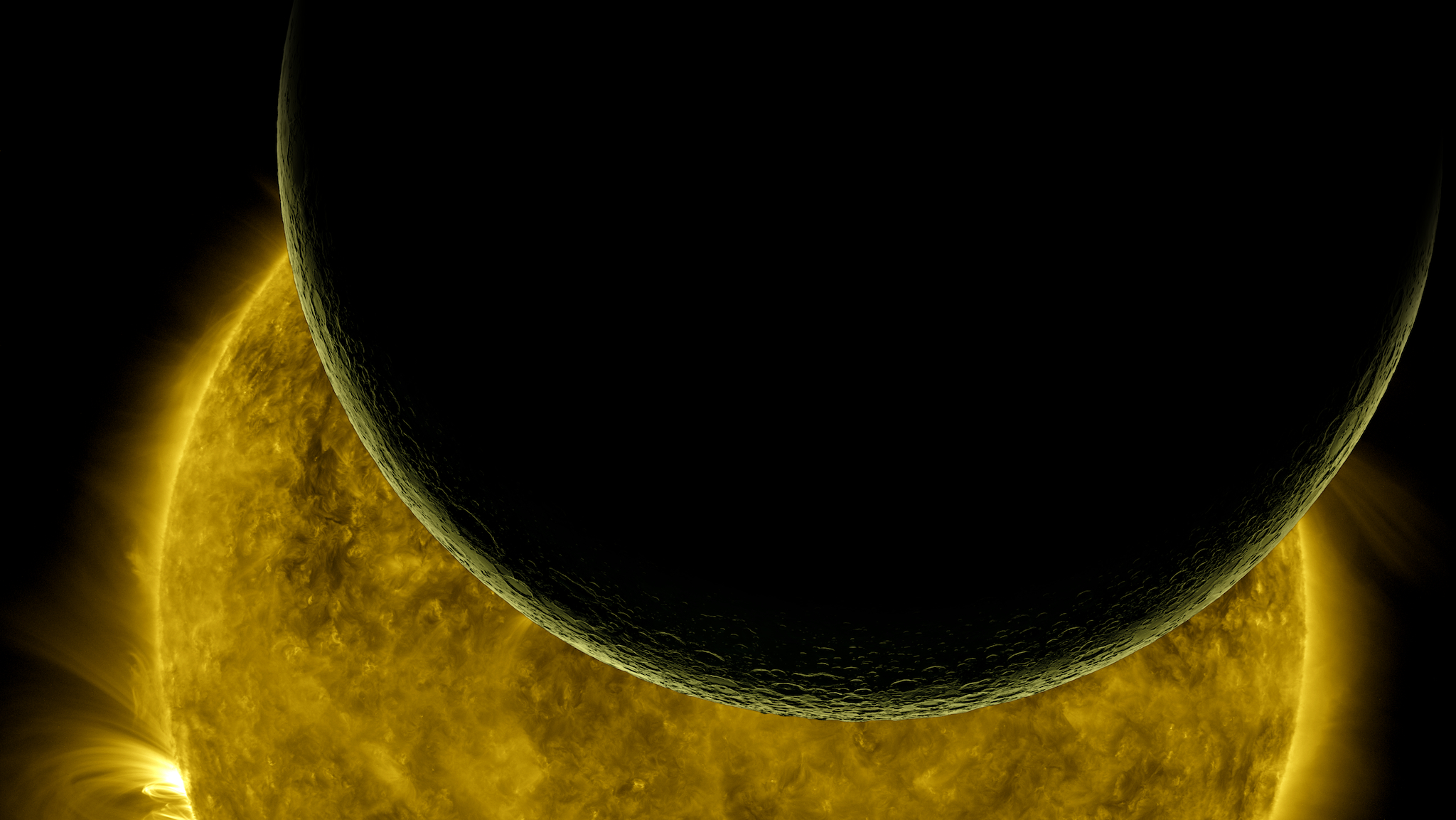

Nitrogen oxides arise as space rocks or space debris fragments, travelling at hyper-sonic speeds, compress the surrounding air as they fall to Earth. The atoms of nitrogen heat up and react with oxygen, creating the harmful oxides.

With the expected increase in rocket launches and the growth of satellite fleets and the subsequent frequency of re-entries, concentrations of these damaging gases and particles could quickly rise. The pollutants could thwart the recovery of the planet's ozone layer, worsening the damage caused by ozone-depleting substances used in aerosol sprays and refrigerators in the past. The air pollution from incinerated satellites could also change how much heat the Earth's atmosphere retains, leading to possibly serious consequences on the planet's climate.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

-

jmurtari How about some serious SPACE news and not scare mongering. Perhaps this writer should work for an environmentalist journal? Think about what might have been said when the first cars and the internal combustion engine were developed -- we might be riding horses today.Reply

The pollutants could thwart the recovery of the planet's ozone layer, worsening the damage caused by ozone-depleting substances used in aerosol sprays and refrigerators in the past. The air pollution from incinerated satellites could also change how much heat the Earth's atmosphere retains, leading to possibly serious consequences on the planet's climate. -

jordiheguilor "When aluminum burns at high temperatures during a satellite re-entry, it produces aluminum oxides, or alumina, a white powdery substance known for its potential to damage ozone and change the reflectiveness of Earth's atmosphere."Reply

So on the one hand alumina damages the ozone layer, on the other it will reflect more heat back into space. It may end up being a wash. -

ultimatewizz Reply

With all the stuff coming back through the atmosphere what makes you use the term significant? Compared to what?Admin said:The rapid unscheduled disassembly of SpaceX's Starship mega rocket may have released significant amounts of harmful air-pollution into the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere.

How much did SpaceX's Starship Flight 7 explosion pollute the atmosphere? : Read more -

DBKelly Reply

I agree, Space.com has problems with Elon.jmurtari said:How about some serious SPACE news and not scare mongering. Perhaps this writer should work for an environmentalist journal? Think about what might have been said when the first cars and the internal combustion engine were developed -- we might be riding horses today.

The pollutants could thwart the recovery of the planet's ozone layer, worsening the damage caused by ozone-depleting substances used in aerosol sprays and refrigerators in the past. The air pollution from incinerated satellites could also change how much heat the Earth's atmosphere retains, leading to possibly serious consequences on the planet's climate. -

DBKelly Reply

Has this site turned into a propaganda rag now, of all the very large objects burning up in the atmosphere such as the Chinese space station, Russian MIr, and you write this article, sounds like you hate Elon Musk, the savior of humanity.Admin said:The rapid unscheduled disassembly of SpaceX's Starship mega rocket may have released significant amounts of harmful air-pollution into the upper layers of Earth's atmosphere.

How much did SpaceX's Starship Flight 7 explosion pollute the atmosphere? : Read more -

Unclear Engineer So, the basic answer to the headline question is "We don't know."Reply

And, while there is some reason to consider the effects of large numbers of satellites burning up completely in the atmosphere, it seems oddly inappropriate to focus such an article on the unintentional destruction of a singe spacecraft that is intended to be reusable and is made of stainless steel instead of aluminum and uses methane instead kerosene for fuel.

In my opinion objective journalists would have titled this article "Should we be worried about the effects of large numbers of satellite burning up in Earth's upper atmosphere." And any mention of the StarShip RUD would have been more to the effect that it isn't the planned occurrence, and isn't as worrisome as routine reentries that are planned in advance and expected to be repeated in large numbers with more worrisome materials.

Space.com, your political biases are showing. -

m4n8tpr8b All the commenters protesting bias but not reading the article properly show their own bias.Reply

Scare mongering? This is reporting on actual work by an actual scientist, and you want to suppress it.

Compared to what? Read the article: "the amount of metallic air pollution potentially produced in the accident equals that generated by one third of meteorite material that burns up in Earth's atmosphere every year".

Space.com does not seem to have any problems with Elon, almost all of their articles on SpaceX are uncritical, even celebratory. You just want to suppress any criticism. -

Unclear Engineer I reread the article and my own critical comment, and stand by my comment.Reply

Part of the problem is, as I already posted, the headline. It clearly uses a "click bait" approach - using the explosion of the StarShip mainly to introduce the topic, which seems to be more related to other space vehicles doing routine reentries.

We can all agree that StarShips should not explode in the atmosphere - even Elon. Nobody wants that to be happening routinely.

But, there is further ambiguity that probably results from the media author - not the scientist. And it seems to be intentionally misleading.

The second paragraph only says that the scientist estimate that the explosion released "45.5 metric tons of metal oxides and 40 metric tons of nitrogen oxides". The next paragraph quotes the scientist as saying "The amount of metallic air pollution potentially produced in the accident equals that generated by one third of meteorite material that burns up in Earth's atmosphere every year." Note that these paragraphs are speaking of total metals, not the aluminum content. There is no comparison of the amount of aluminum released by the StarShip explosion to the amount of aluminum that enters Earth's atmosphere annually.

The article does say, a couple of paragraphs later, "Fortunately, the Starship upper stage is made of stainless steel and not aluminum like satellites and upper stages of many other rockets including SpaceX's Falcon 9. The incineration of aluminum is what worries many scientists."

But, the article never says what amount of aluminum oxide was released by the StarShip explosion compared to naturally occurring meteors. On careful reading, one might conclude zero alumina was released by StarShip because it was built with stainless steel. But, what sticks in the mind is the "one third of meteorite material" for all metals.

That is a rhetorical trick, much used by lawyers, politicians, biased journalists and others with agendas they are trying to sell. It is called "misdirection" instead of "lying" because it tends to make people think they heard something you did not actually say but want them to believe. Their defense when caught is "I didn't say that!"

So, as an objective scientist, I want to know how much alumina the StarShip explosion put into the atmosphere, and how that compares with the natural annual input of alumina from meteors. Since that is the issue the article is worried about, that is that information it should have provided, considering the headline it has, making the StarShip explosion appear to be the main subject.

Similarly, the amount of nitrogen oxides produced by the explosion should have been compared to the amount produce naturally by meteors. That was sort of addressed by the statement "The amount of nitrogen oxides produced during re-entries is also nearing that generated by natural space rocks." But, again, is this more misdirection? That statement appears to be referring to all of spacecraft reentering the atmosphere, not the StarShip explosion.

In fact, the article really doesn't even address whether the amount of nitrogen oxides produced by the planned, intact reentry of a StarShip is any different from what was generated due to the explosion. Again, the article seemingly relates the creation of the nitrogen oxides to the explosion, tending to make it read like the nitrogen oxides were carried by the StarShip. But, in fact, it was all made from the oxygen and nitrogen that was already in the upper atmosphere - and doesn't even address how that compares to the amount that would have been created by the reentry of the intact StarShip.

So, what is really accomplished by this article in the way of properly informing the readership about potentially important issues? Not much. It raises the issues, but really does not put them into properly useable perspectives. It does explicitly mention SpaceX and StarShip in that context, without putting them into perspective with the other launchers who also contribute.

I challenge the authors and editors of Space.com to provide an objective, fact-based and well referenced article on the subject with a headline of "Launch and Reentry Effects on Earth's Upper Atmosphere In Perspective". Maybe if they read the articles from other sources, such as https://phys.org/space-news/ , they can get a better feel for the desired journalistic approach. And look for potentially positive effects to the same degree as the potentially negative effects. Just mentioning the possibility of a positive effect and then dwelling on the negative effects is a common human tendency, but it is not objective.

Is alumina building up in the ionosphere and thermosphere? Is ozone declining, and by what percent per year or percent per unit weight of alumina? Does the alumina change the reflectivity of the upper atmosphere? What effect does this have on global surface temperatures?