An ancient 3-star system give this 'blue lurker' a turbo boost, Hubble Space Telescope reveals

"We have by and large been ignoring triples in models and simulations — we're just starting to understand how these types of systems evolve."

If you gaze at the night sky on a clear night, especially from a remote corner of Earth, you'll see a vast sea of stars strewn across an endless black canvas that shimmer like exquisite sequins but offer few clues to their pasts. Yet, each one carries its own unique history spanning billions of years, all written in its light, chemical makeup and behavior measurable by telescopes.

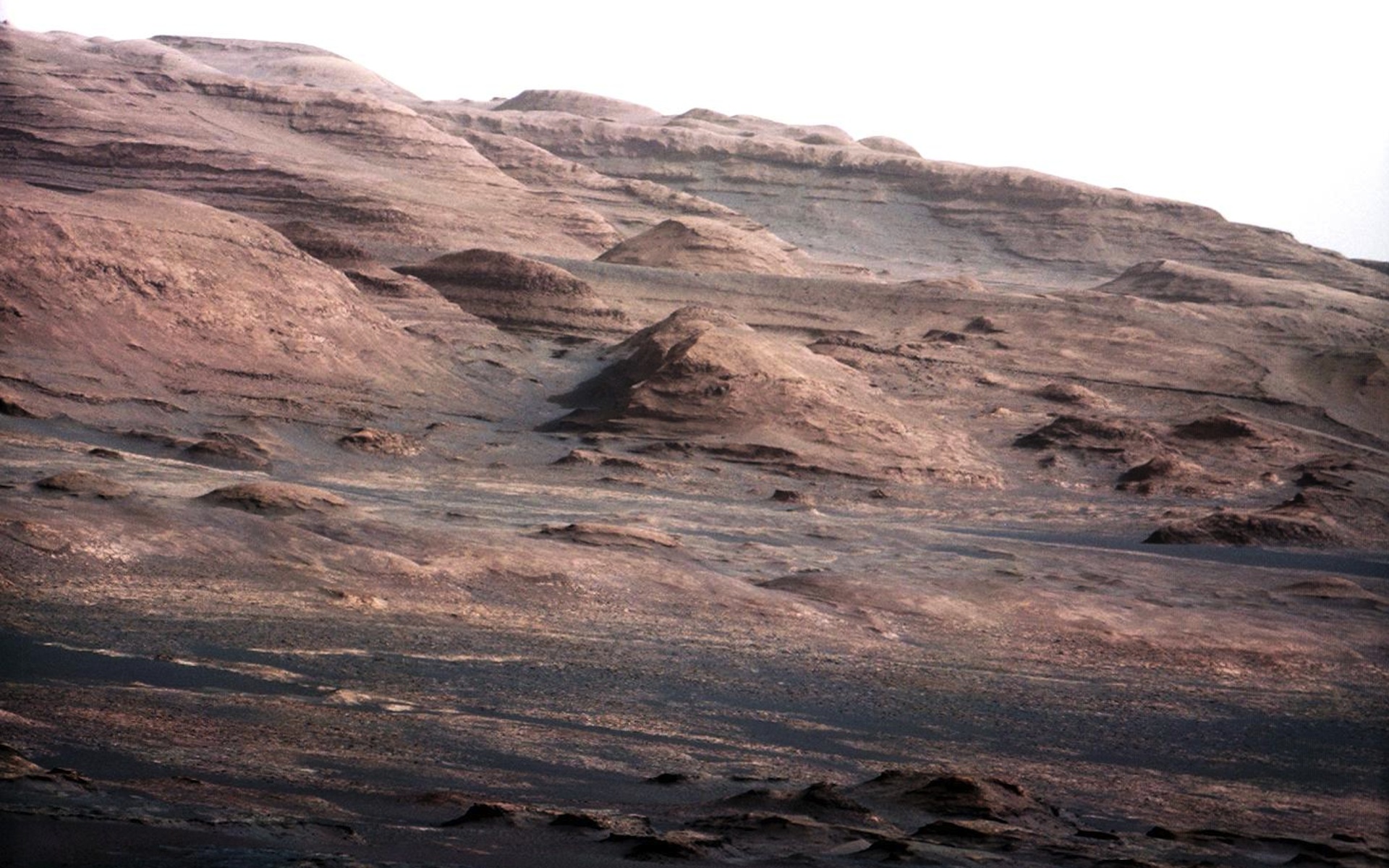

In deciphering sagas of eons past, astronomers find few examples more intriguing than Messier 67, or M67, which is a large, loosely bound group of sun-like stars dwelling in the outskirts of the Milky Way, our home galaxy. Previous observations led by astronomer Emily Leiner using NASA's retired Kepler space telescope had revealed that all of M67's 500 stellar residents are about four billion years old, save for a bright smattering of so-called "blue lurkers." This term, coined by Leiner and her team, describes 11 puzzlingly young stars in M67, which were also found to spin at perplexingly high speeds — at least 10 times faster than expected for their ages.

These stars "look totally normal, but are spinning suspiciously fast for their age," Leiner, who is an assistant professor of physics at the Illinois Institute of Technology, told reporters on Monday (Jan. 13) at the 245th American Astronomical Society meeting being held this week in Maryland. "What on Earth was happening?"

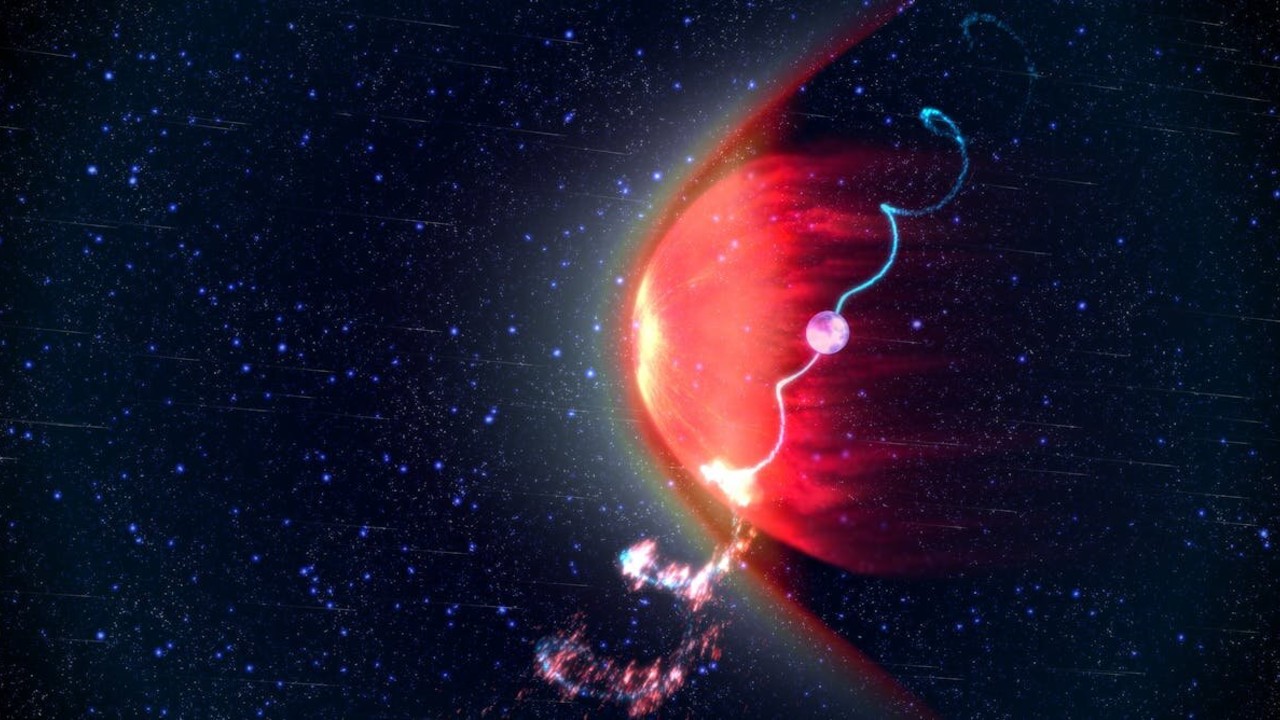

Determined to find out, Leiner and her colleagues attained and analyzed fresh Hubble Space Telescope observations of one of the brightest blue lurker stars in M67 — the results suggest it was, in fact, once part of a remarkable triple-star system. Possibly, it gained its observed turbo boost thanks to being a bystander while its two stellar siblings chaotically merged millions of years ago.

This evolutionary history, detailed in a paper published on Jan. 13 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, marks a rare instance where astronomers have unraveled the story of an ancient triple star system in such detail. The findings would help stellar evolution models account for other similar three-star systems that once hosted binaries that merged into single stars. That's important, according to Leiner, because triple star systems are fairly common, yet identifying them has proven challenging.

"We have by and large been ignoring triples in models and simulations — we're just starting to understand how these types of systems evolve," she said during the briefing.

A chunk of that knowledge came to light when Hubble observations of the blue lurker revealed it was not a standalone star, but rather was locked in a gravitational dance with the smoldering remains of a once-massive star known as a white dwarf. While white dwarfs are already incredibly dense, this one was "far more massive than it should have been — so massive, in fact, that it could not have formed like any normal star in this cluster," Leiner said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers' best guess is that the white dwarf is a telltale remnant of an inevitable merger of stars that once orbited each other every few days. A third star circled them much farther out, completing one orbit every few thousand days. Around 500 million years ago, the inner binary would have merged, coalescing into a massive star that weighed three times our sun — much heavier than a typical star in the M67 archive.

The blue lurker star, which survived this mayhem as an onlooker, was later coated with material expelled by the merged star as it swelled during its evolution, causing it to spin up. Not long after, the two stars would have inescapably spiraled inward, shrinking their orbit from the original 3,500 days to the observed 359 days. "The white dwarf is much more massive because it descended from that merger," Leiner said.

Despite the tumultuous past in its cosmic residence, the blue lurker looks like any other sun-like star in telescope snapshots of M67. Up close, however, it sports "all sorts of" starspots on its surface and loops of scathingly hot plasma reaching out into space — both driven by the fast-spinning star's turbulent magnetic field, said Leiner.

"This was our only clue that this entire complicated evolution had happened, and there was ever another star sitting there."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social