Can Hubble still hang? How the space telescope compares to its successors after 35 years of cosmic adventures

"It's amazing that after 35 years, Hubble still holds a unique capability as a top workhorse for science discoveries and publications."

This Thursday (April 24), the Hubble Space Telescope celebrates 35 years in space — and even though Hubble has continuously delivered stunning space images and vital data since 1990, it isn't unfair to ask whether the instrument can still deliver goods with the same level of quality. Thirty-five years of age for a space telescope is no joke.

So, can Hubble still hold its own and prove itself useful when compared to other, more recently built space instruments like NASA's $10 billion golden goose, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST)?

Well, as it appears, the answer is yes.

Kurt Retherford is a Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) scientist who argues that Hubble can still hold its own. For instance, he recently used the long-serving space telescope as part of a program to study the solar system's most volcanic body" Jupiter's moon Io.

"It’s amazing that after 35 years, Hubble still holds a unique capability as a top workhorse for science discoveries and publications," Retherford told Space.com. "The requested time amongst scientists to use this facility remains several times higher than the time being competed for, meaning only the best of the best ideas for observations are conducted."

Did the JWST make Hubble obsolete? No way!

Of course, when talking about space telescopes and their usefulness, we have to mention the $10 billion elephant in the room: the JWST.

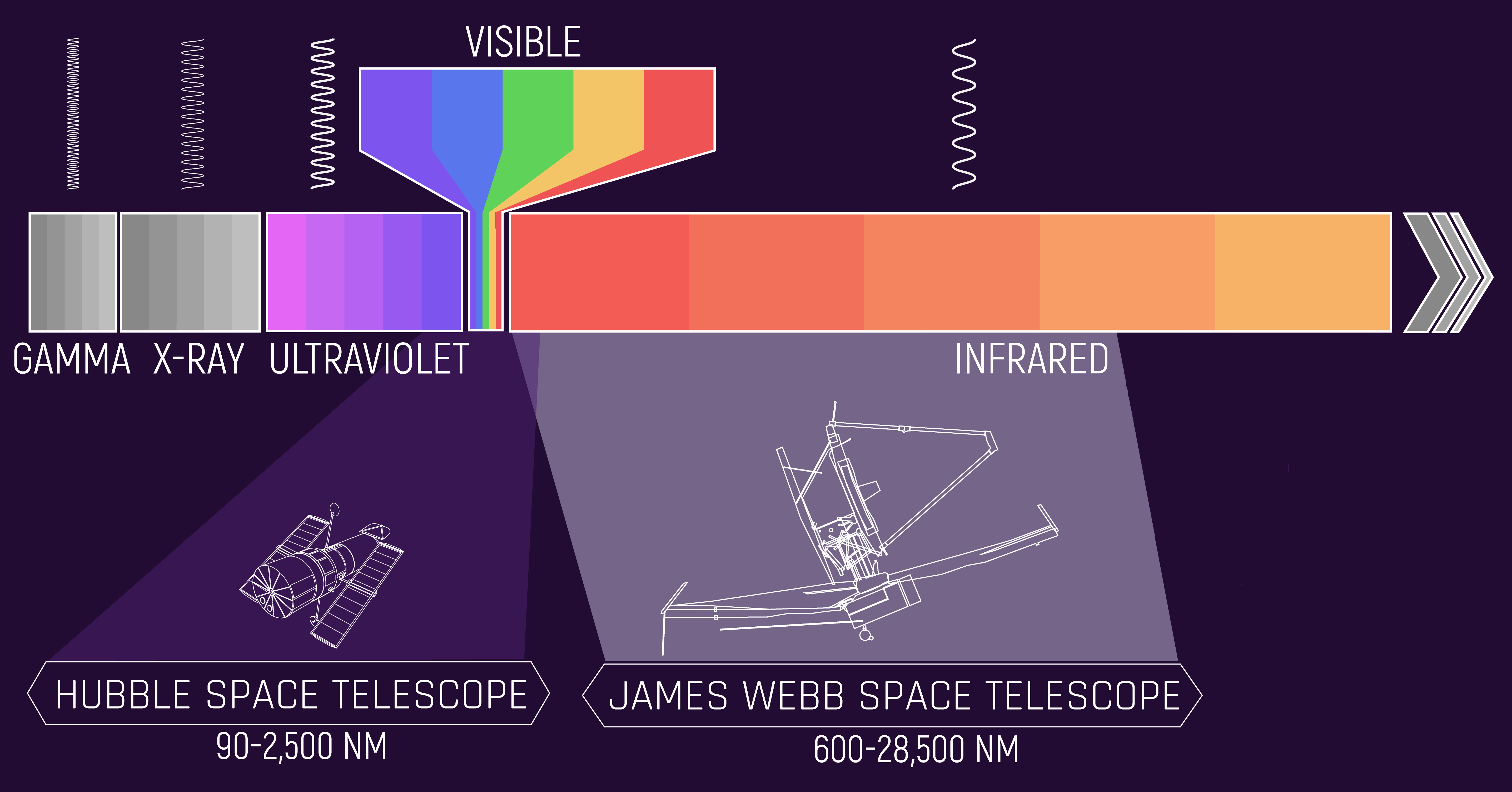

Why do we still need Hubble with the JWST out there? The answer concerns the way these two revolutionary instruments use the electromagnetic spectrum to see the cosmos.

"Hubble is different than JWST in that it is great at imaging both the visible light that we see with our eyes and light at ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths, even shorter and more energetic than the light that gives us sunburns," Retherford said. "JWST, on the other hand, is optimized to detect infrared light, even at thermal temperatures that are even redder than night-vision goggles use. Both are big telescopes, but they are very different in these ways."

As Retherford pointed out, in terms of the wavelengths of light these two telescopes are optimized to observe, the JWST in fact picks up where Hubble leaves off.

That means that the observations conducted with these two space telescopes are highly complementary, especially when studying transient cosmic phenomena that change in wavelength over time — that includes the solar system's planets and their moons.

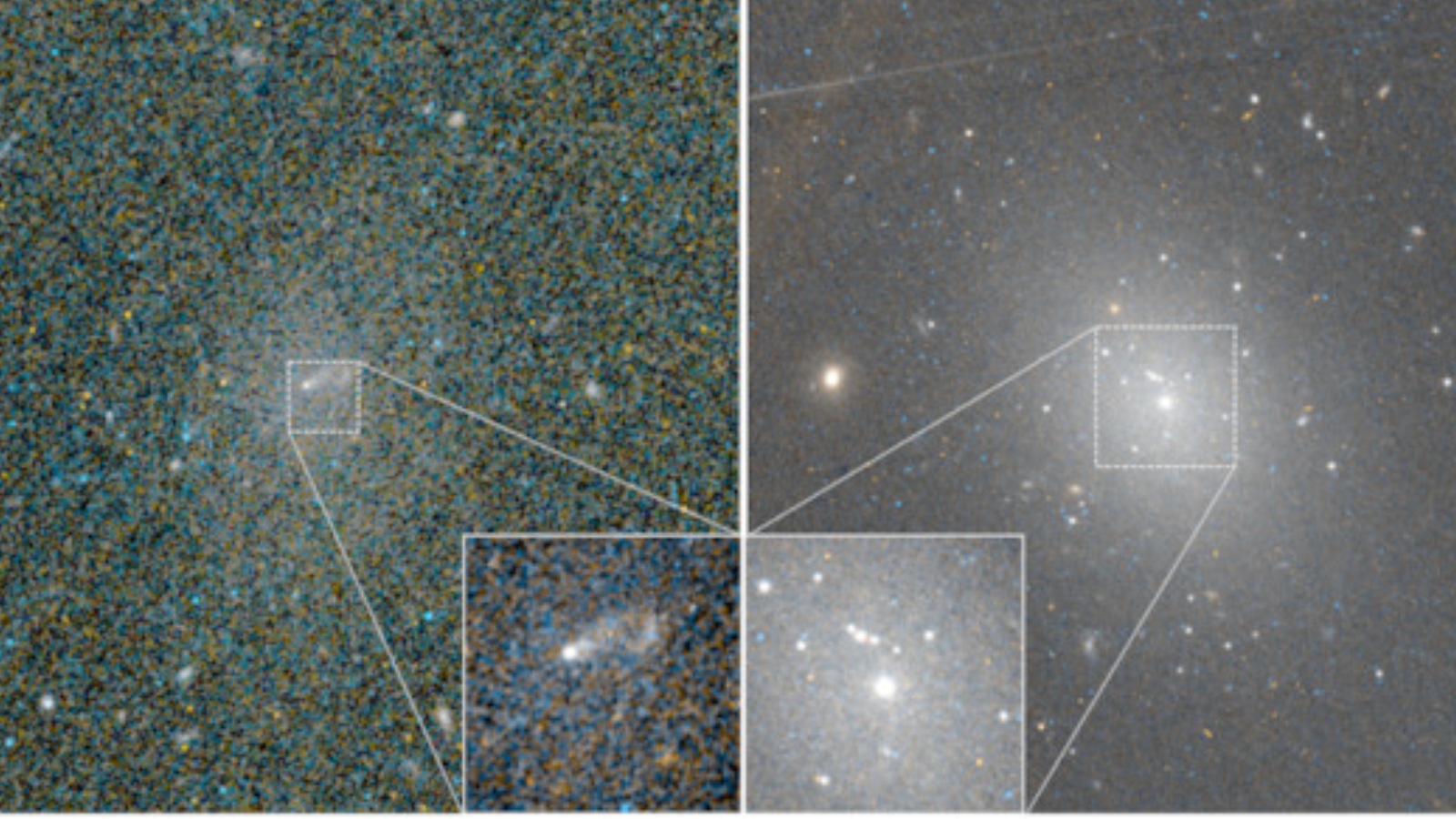

University of Oulu researcher Mélina Poulain was recently part of a team of astronomers that used Hubble to study around 80 dwarf galaxies, with the loyal space telescope making the first ever detection of star clusters colliding at the hearts of these diminutive and faint galaxies.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Hubble's field of view and spatial resolution allow for a very detailed study of plenty different astronomical sources from planets to galaxies, including those with very low surface brightness objects like dwarf galaxies," Poulain told Space.com. "It can also observe blue and near-UV wavelengths, which has become a rare feature."

Poulain also suggested that even though Hubble may one day be surpassed by other telescopes like the JWST and the European Space Agency's Euclid spacecraft, there is another key aspect keeping Hubble relevant: familiarity.

"Hubble is an easy choice, as people do know what to expect from Hubble observations and how to handle them. JWST is still at the beginning of its operational lifetime," Poulain said. "Moreover, I feel like there is an extremely high demand, and thus high competition, for getting observation time currently."

Hubble's future is all about teamwork

When it comes to the future for Hubble, however, the emphasis is very much on synergy with the JWST and other telescopes both in space and planted on terra firma.

"Why do the JWST and Hubble make such a good team?" Poulain pondered. "They both have a similar field of view and spatial resolution, and they are complementary in terms of filters used: Hubble offers a view in the optical, while the JWST observes in near-infrared and infrared bands."

Currently set to launch by May 2027, NASA's next major space observatory project is the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Roman has been designed to complement the high resolution and sensitivity of the JWST, thus building on the success of that telescope and Hubble.

While Roman may muscle Hubble out a bit by forming a more synergistic partnership with the JWST, plenty of observatories would still benefit from a team-up adventure with Hubble.

The long-serving space telescope could be particularly useful when collaborating with future ground-based observatories, including the Vera Rubin Observatory on Cerro Pachón in Chile, which is currently nearing completion.

First light for Rubin is expected later this year when the observatory will begin conducting the decade-long Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST).

"While Hubble and JWST are designed to provide exquisite spatial resolution of targets along a tight, pencil-beam type line of sight, the Rubin Observatory will scan the sky in fields of view a few times larger than the full moon, night after night, detecting all sorts of new things," Retherford said. "I'm very excited about all of the objects discovered by Rubin that Hubble and JWST will be able to then go and image and survey in UV and infrared wavelengths in more detail, respectively."

Poulain added that while Rubin won't be able to resolve features as small as those determined by space telescopes, it will offer deep observations in specific optical features. This will allow for stellar population studies through a process called Spectral Energy Distribution mapping.

"It will also add a time variable so we can search for object variability over time, which is a good tool to identify some astronomical sources such as supernovae or supermassive black hole-powered active galactic nuclei," Poulain said.

"I couldn't be more excited for future Hubble findings," Retherford explained. "I hope Hubble keeps working until our Europa Clipper and JUICE [Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer] missions to Jupiter's moons arrive and operate in the 2030 to 2036 timeframe so that we can coordinate observations.

"For sure, I'll continue to use Hubble and have no shortage of good ideas to propose."

The biggest threat to the future of Hubble doesn't come from other space telescopes like the JWST and Rubin, but rather from an internal challenge that jeopardizes those missions too.

"Unfortunately, the funding situation for NASA science projects is looking dire in the next few years, and the US likely won’t have enough funds for scientists like myself to take full advantage of our national treasures like Hubble, JWST, and the fleet of planetary and heliophysics missions already operating and partially built," Retherford concluded. "Much less likely is a new start for the next big observatory to come after JWST, the Habitable Worlds Observatory, which is more of a true replacement for Hubble’s UV and visible light capabilities."

Let's hope Hubble can hang on until its true replacement and NASA's next big mission after Roman, the Habitable Worlds Observatory, can get off the ground, or maybe until its 40th birthday in 2030?

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.