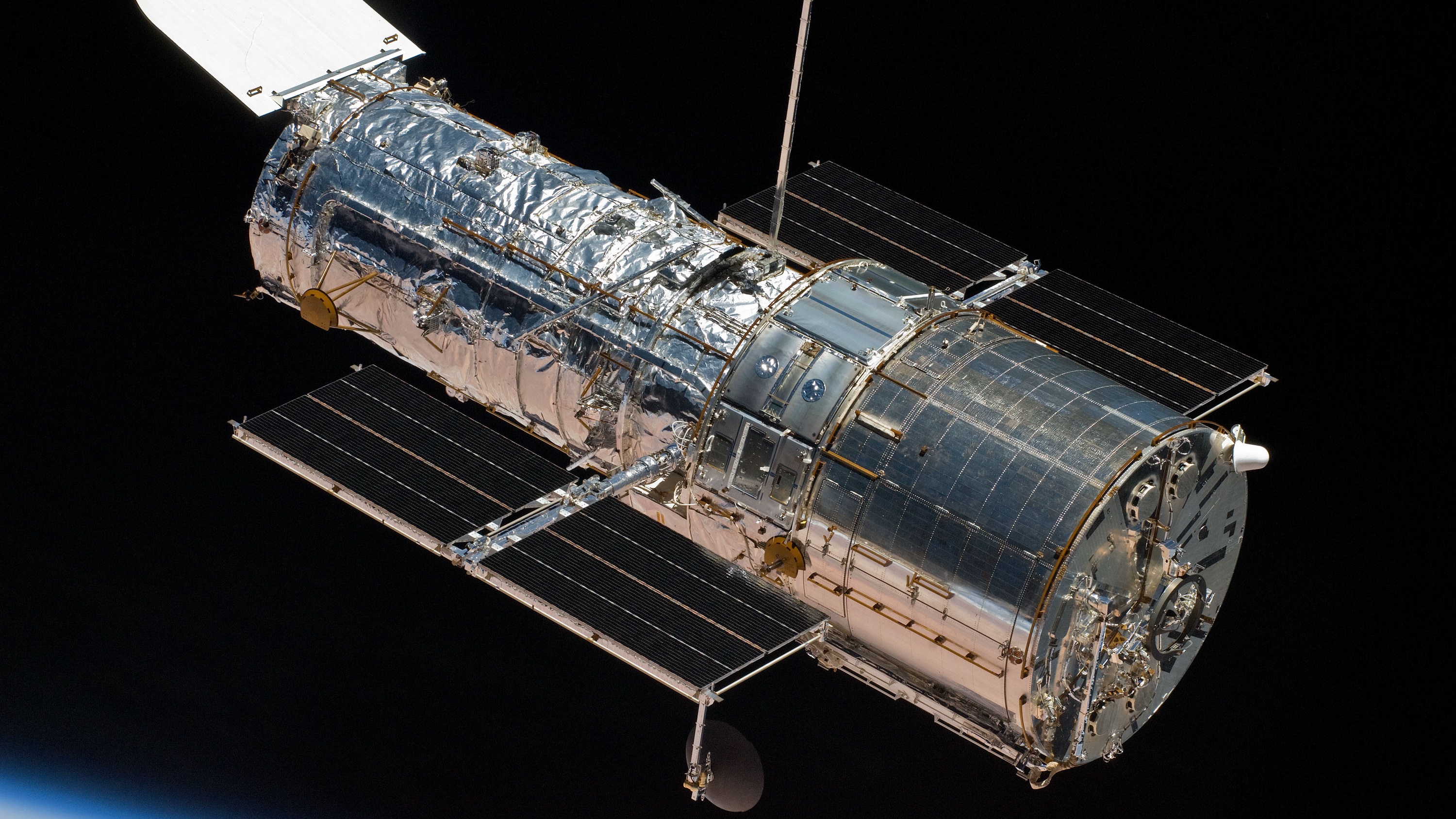

The Hubble Space Telescope is still going strong thanks to an amazing design, operations and science team — and a cadre of spacewalking astronauts.

Hubble launched to Earth orbit 35 years ago today (April 24) with a flawed primary mirror, an image-blurring defect that made the scope the butt of jokes and put its entire ambitious mission in jeopardy.

But Hubble was designed to be serviced in orbit, and astronauts did just that during a space shuttle mission in December 1993. They fixed the mirror problem, giving Hubble the far-reaching 20/20 vision that has made the observatory a scientific powerhouse and an ambassador for the beauty and wonder of the cosmos.

But that wasn't the end of the Hubble hugging: Astronauts visited the observatory four more times, on space shuttle flights in February 1997, December 1999, March 2002 and May 2009.

The spacewalkers did a variety of work on these servicing missions, from installing new and improved scientific instruments to replacing critical hardware such as gyroscopes, the devices that allow Hubble to point precisely at its targets. Their combined efforts allowed the mission to keep humming along for three and a half decades (and counting).

Related: Fixing the Hubble Space Telescope: A timeline of NASA's shuttle servicing missions

But Hubble is showing signs of its advanced age. Last year, for example, the mission team shifted the scope into one-gyro mode after yet another of the devices failed. (Two of Hubble's six gyroscopes are functional at the moment, but the team put the other healthy device on the shelf to save it for future use.) Hubble can still train its powerful eyes on targets, but it now takes longer for the scope to slew from one object to another.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

More worrisome, however, is the observatory's inevitable orbital decay: As Hubble circles Earth, the thin, scattered molecules at its altitude create friction, dragging the scope down slowly but continuously.

The space shuttle Discovery deployed Hubble at an altitude of 380 miles (610 kilometers) on April 24, 1990. The scope currently orbits about 326 miles (525 km) above the planet — and that's after the five servicing missions, each of which gave Hubble a slight altitude boost.

Atmospheric drag accelerates the lower you go, as the air gets thicker and thicker. NASA estimates that Hubble will be pulled down to a fiery death in just 10 years or so if nothing is done.

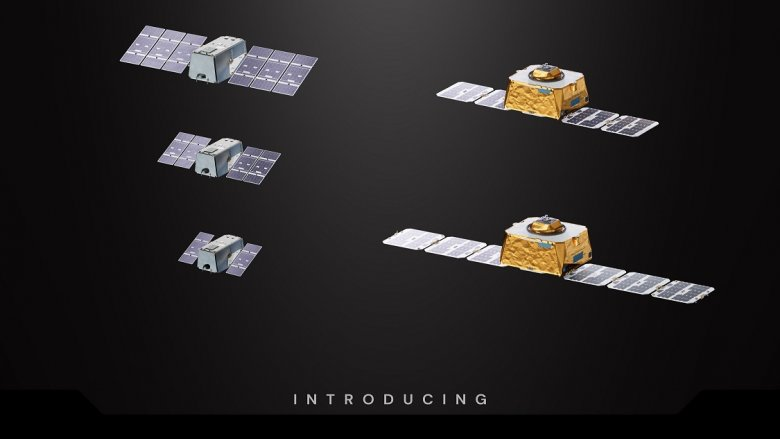

But something could be done — theoretically, at least. In 2022, SpaceX private astronaut and billionaire entrepreneur Jared Isaacman proposed launching a private mission to boost, and also perhaps repair and upgrade, the famous telescope.

Such a mission would use a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon crew capsule. It was floated as a possible part of the Polaris Program, a series of private orbital spaceflights that Isaacman is organizing, funding and commanding.

Isaacman was a serious player; he'd already commanded SpaceX's Inspiration4, the first all-private human orbital flight, which launched in September 2021. So NASA took the proposal seriously, organizing a study and asking other companies to send in their ideas as well.

Last year, however, the agency announced that it had passed on the SpaceX-Isaacman Hubble-boosting mission, saying that the risks seem to outweigh the potential benefits.

After all, entirely new rendezvous and docking procedures would have to be devised for Dragon, which was not designed to service Hubble; the capsule has no robotic arm and no airlock, and it had not supported a single spacewalk at the time that NASA made its decision. (NASA retired its space shuttle fleet in 2011, so using one of the winged orbiters again is not an option.)

Loss of institutional knowledge was also an issue; the most recent Hubble servicing mission occurred nearly 16 years ago, so many of the people who mapped out such a complicated endeavor have retired or moved on to different jobs.

Specific worries were also nested within these general concerns. For example, NASA officials noted that Dragon's thruster exhaust could potentially contaminate Hubble's supersensitive optics.

But the agency's decision was not a permanent, blanket "no." NASA officials stressed at the time that they would be open to revisiting the plan if and when the risk-reward ratio changed — when Hubble's drag-down date is closer at hand, for example, or if the scope suffers some sort of setback.

"While the reboost is an option for the future, we think we need to do some additional work to determine whether the long-term science return will outweigh the short-term science risk," Mark Clampin, director of NASA's Astrophysics Division, said on June 4, 2024, during a press conference about Hubble's newly failed gyroscope and the decision to move to one-gyro operations.

Related: The Hubble Space Telescope turns 35 as NASA budget cuts loom. How many more birthdays will it have?

And the situation is set to change soon, in another way that could facilitate a private Hubble-boosting mission: Isaacman is in line to be the next NASA chief.

President Donald Trump nominated Isaacman for the post on Inauguration Day, and the U.S. Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation held a confirmation hearing for him earlier this month. Things seemed to go well, and Isaacman appears on track to take NASA's reins in the coming weeks.

It's unclear if Isaacman would push for another look at a private Hubble-boosting mission if confirmed as NASA administrator. But he obviously believes strongly in the merits of such a plan.

"Had a mission been flown, and I was happy to fund it, I believe it would have resulted in the development of capabilities beneficial to the future of commercial space and along the way given Hubble a new lease on life," Isaacman wrote in an X post last year, after NASA made its decision.

He, and private spaceflight, have also made strides since then. Isaacman funded and commanded Polaris Dawn, a private SpaceX flight that circled Earth for nearly five days last September.

During Polaris Dawn, the first flight of the Polaris Program, Isaacman and his three crewmates got farther from Earth than any people had been since the Apollo era. The mission also performed the first-ever private spacewalk, showcasing gear and know-how that could potentially be put to use on a Hubble servicing mission.

Will such a mission ever get a green light? We don't know, but it's certainly worth keeping an eye on, especially as Hubble continues to age and Earth's atmosphere drags it closer and closer to a fiery death.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.