Space mysteries: How does the ISS stay in orbit without falling to Earth?

The secret behind how the International Space Station remains in orbit can be traced all the way back to the genius of Sir Isaac Newton.

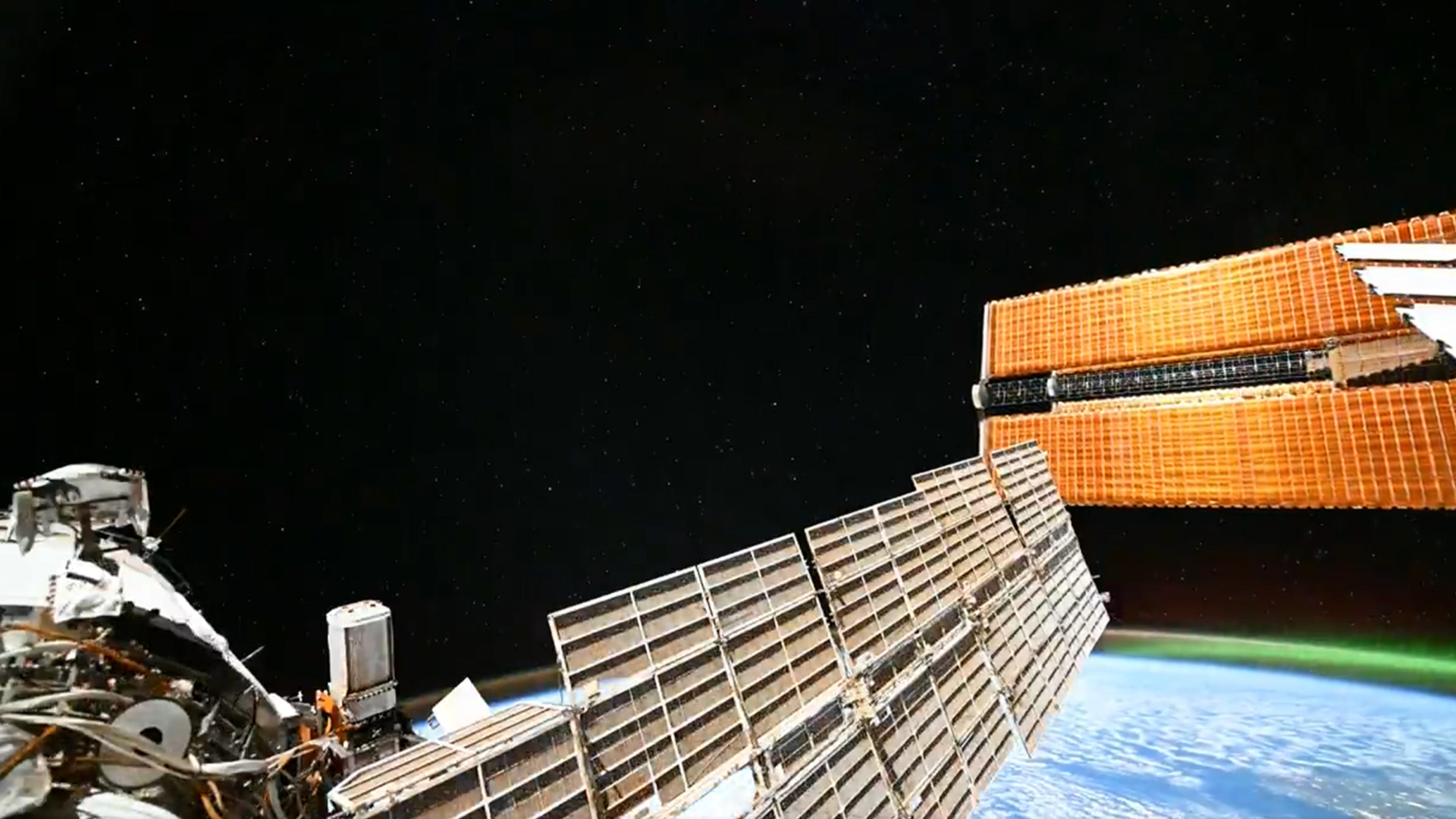

The International Space Station (ISS) orbits high above our heads, yet the pull of Earth's gravity never hauls the complex out of orbit and sends it plummeting through our atmosphere, where it would burn up.

Here's a little secret: The ISS is always falling! Yet it never crashes to Earth or burns up in our atmosphere. How is this possible?

It sounds miraculous, but it is not a paradox or magic, simply the result of good old fashioned physics. It all comes down to the International Space Station's orbital velocity, its height above the ground, and the rate at which it is falling under gravity.

The science and mathematics behind what keeps the ISS in orbit goes all the way back to the father of gravitational theory, the 17th-century English scientist Sir Isaac Newton. Famously grumpy, Newton probably didn't come up with his theory of gravity from idly sitting and daydreaming beneath a tree while an apple fell on his head, as the old story goes. But he would have observed apples, leaves and other things falling and wondered why they did so.

Related: International Space Station: Everything you need to know about the orbital laboratory

To begin, let's think about that apocryphal falling apple. When it is hanging on a branch, it is stationary, so when it drops, gravity pulls it straight down. Suppose, though, that you pick the fallen apple up and then throw it like a ball. The apple doesn't drop straight down like it did when it was stationary; now it has horizontal motion competing against gravity, and it follows a curve down to the ground.

Newton used the analogy of a cannonball, fired horizontally, following a similar curve back down to the ground. The size and shape of this curve depends upon the velocity of the cannonball and the amount of air resistance. The faster the cannonball and the lower the air resistance, the greater the distance the cannonball travels and the shallower the angle of the curve that the cannonball follows back to the ground.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So Newton theorized that, were a cannonball to be fired horizontally from a high enough mountaintop where the air is thin, and with enough velocity, then the curve of the cannonball downward under gravity would match the curvature of Earth. It would keep falling, following this curve, without losing altitude because the planet would be curving away from it at the same time. Scientists call the force acting on an object to keep it following such a curved path a centripetal force, which is always directed toward the center of curvature.

Height and velocity

This is the premise behind what keeps the ISS happily orbiting above our heads. It's a balance between the centripetal force directed toward the center of Earth and the force of Earth's gravity that's constantly causing the ISS to undergo gravitational acceleration around its curved path. The rate at which the ISS falls as it follows its curved path equals the rate at which the curved surface of Earth drops away below it.

This balance is achieved with certain combinations of height and orbital velocity. The ISS orbits at a height of about 402 kilometers, or 250 miles (we'll explain why we describe it as "about" shortly) and is traveling at 7.6 kilometres (4.7 miles) per second, which is the velocity required at this height in order to keep following the path that matches the curvature of Earth. Were the ISS orbiting Earth at a greater height, it would not need to travel as fast to maintain the rate of curvature of its fall. Were the ISS at a lower altitude, it would have to travel faster to avoid dropping into Earth's atmosphere and burning up.

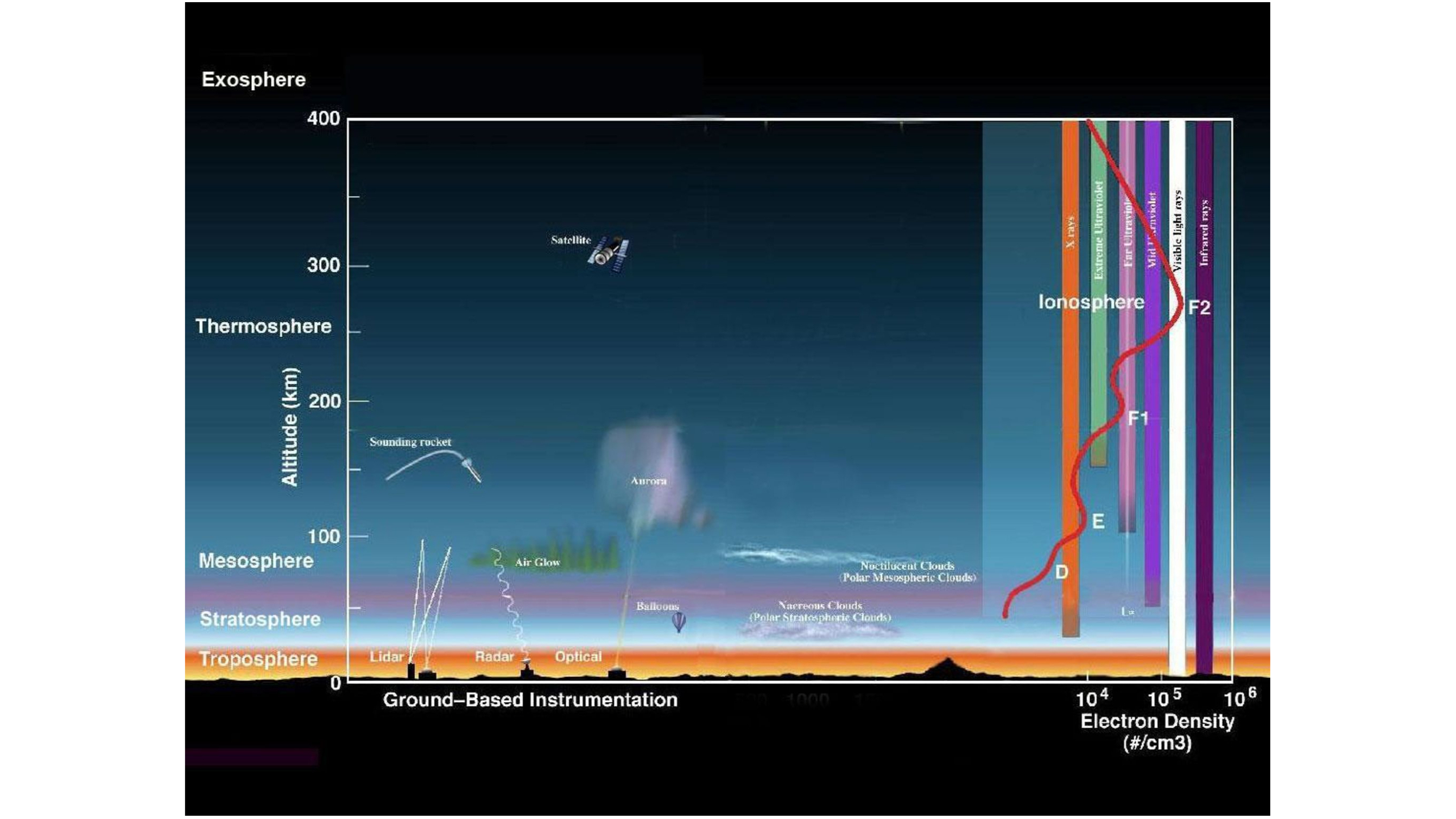

There are some complications, though, which mean that the ISS cannot be left to its own devices indefinitely — eventually it would come crashing back down through the atmosphere and burn up if we didn't intervene. That's because, even at 402 kilometers above the surface, the ISS is still within Earth's atmosphere, albeit in a very thin part of the atmosphere called the thermosphere. The thermosphere has a very low density, meaning that atmospheric molecules are scarce, but there's still enough to resist the ISS's motion and create enough drag to slow it down. This results in the space station decelerating by about 5 centimeters (2 inches) per second, causing it to lose about 100 meters (328 feet) in altitude above Earth's surface each day.

This is why we said that the orbital altitude of the ISS is "about" 402 kilometers, because it is constantly losing height. Every month or so, the ISS has to fire its thrusters to push it back up to its intended orbital altitude. If the ISS didn't have some way to elevate its orbit, it would eventually fall deeper into the atmosphere and ultimately burn up, like a huge meteor.

Related: The International Space Station will eventually die by fire

Why the ISS will burn up eventually

One day, however, we will be forced to abandon the ISS — and this day is coming relatively soon. Construction on the space station began in 1998, and the oldest parts of the ISS are now over a quarter-century old and are beginning to creak a little with increasing age. Within a few years, the ISS will outlive its usefulness, and once it is abandoned there will be nothing to keep it at the proper altitude.

The huge size of the ISS, which is 109 meters (358 feet) long and 73 meters (239 feet) wide, means it is too dangerous to allow it to fall back into the atmosphere on its own: Although much of it will burn up, significant chunks of ISS debris could rain across the land, possibly over an inhabited area.

So the plan is for the ISS to be deliberately deorbited in 2031 over a remote region of the Pacific Ocean called the "Spacecraft Cemetery." A spacecraft-tug will launch in 2030 and dock with the ISS. By this time, the last crews will have left the ISS and turned out the lights. The space-tug, latched onto the ISS like a limpet, will wait 12 to 18 months for the ISS' altitude to naturally decay from 402 kilometers to 220 kilometers (140 miles). The tug will then fire its engines, pushing the ISS even lower, to 150 kilometers (93 miles). Then, a final engine burn will bring the space station down into the mesosphere, which is the layer of the Earth's atmosphere beneath the thermosphere.

The mesosphere is denser than the thermosphere, and it is in the mesosphere where meteors from space burn up — when we see a shooting star, it's a grain of cosmic dust burning up in the mesosphere located between 50 and 80 kilometers (31 and 50 miles) above us. (Also, noctilucent, or "night-shining," clouds seen during the summer months form in the mesosphere.)

Things burn up in the mesosphere because of the energy produced through friction between the object falling through the mesosphere and the molecules in the mesosphere. Meteors usually burn up entirely because they are small; it takes a big chunk of space rock to survive passage through the mesosphere and reach the surface as a meteorite (and even then, most of it will have burned away).

As we've seen, the ISS is huge, and large parts of it will survive the flaming fall through the mesosphere intact. The space-tug's job, therefore, will be to push the ISS to enter the atmosphere over the Spacecraft Cemetery, in the remotest stretch of the Pacific Ocean, where any debris will splash down into the water far from land, shipping lanes and aircraft flight paths. Any pieces of the ISS that do survive atmospheric re-entry will sink to the ocean floor, never to be seen again.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.