Will the International Space Station's 2031 death dive cause pollution problems?

Some people have begun asking the question.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

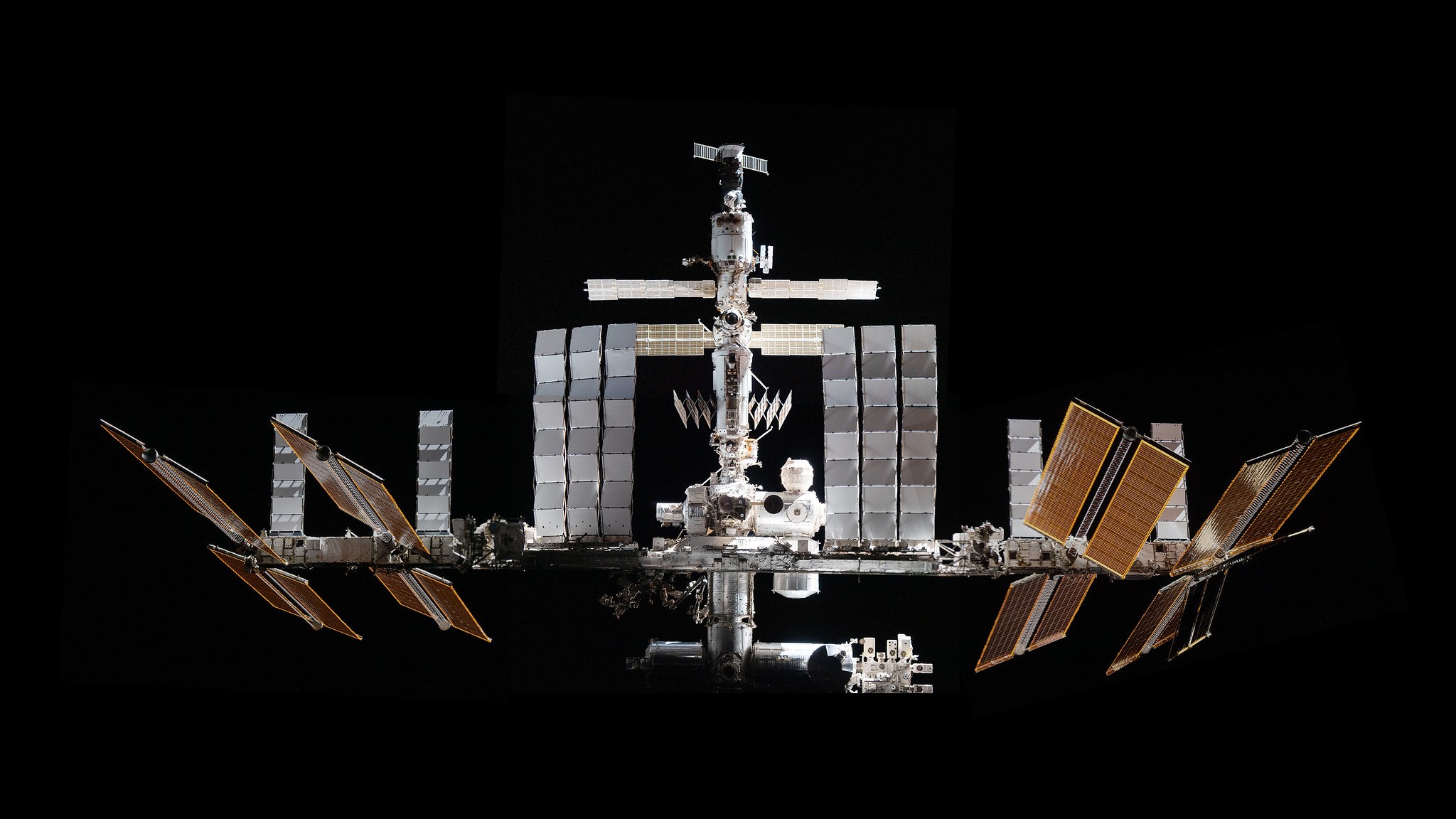

The International Space Station is something of a problem child.

The orbital outpost is plagued by cracks, coolant and air leaks, even a surprising smell that recently wafted into the station from a just-arrived Russian Progress cargo ship. And the station has high-speed, close encounters with space junk from time to time that make the facility a risky residence. So, there's escalating worry that the aging complex has become a questionable home for crews to be safe and sound.

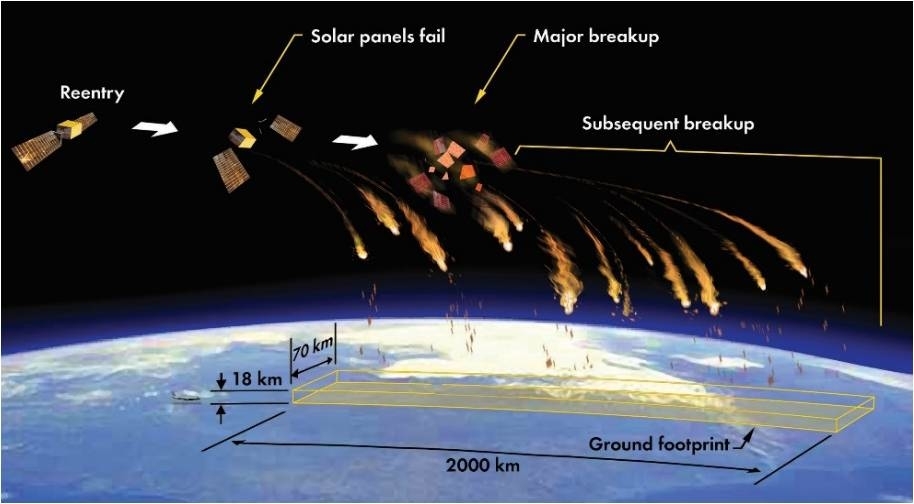

Sustaining International Space Station (ISS) operations through 2030 may therefore be somewhat touch-and-go, prior to its planned 2031 "safe, controlled deorbit" into remote ocean territory. And some people are starting to question just how safe that suicide dive will be, as it could end up polluting Earth's air and water.

Elvis Presley maneuver

The coming death plunge might well be labeled the Elvis Presley maneuver, one that renders the ISS "just a hunk, a hunk of burning love," as its temperature rises higher and higher while diving violently into Earth's atmosphere.

Related: Watery graves: Should we be ditching big spacecraft over Earth's oceans?

The likely ocean zone for plopping the ISS down in a controlled fashion is within the South Pacific Oceanic Uninhabited Area, a region around Point Nemo formally known as "the oceanic pole of inaccessibility." That area is farther from land than any other point on Earth and is often labeled the world's largest "spacecraft cemetery."

This remote seascape is about 1,450 nautical miles (2,685 kilometers) from the nearest piece of dry land. The closest terra firma is Ducie Island, part of the Pitcairn Islands, to the north; Motu Nui, one of the Easter Islands, to the northeast; and Maher Island, part of Antarctica, to the south.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nevertheless, the station's planned end-of-life plunge is stirring up concern in environmental and space research circles, with specialists weighing the pros and cons of any dedicated ISS "retirement."

There are those wondering about the incineration and implications for Earth's atmosphere and sea waters. Similarly, what about a "hit and miss" scenario that has chunks of the station reaching the ground due to a botched reentry process?

Little or no warning

Earlier this year, the Aerospace Safety Advisory Panel (ASAP), an advisory committee that reports to NASA and Congress, issued its 2023 annual report. Within its pages, it advised and reemphasized an ASAP recommendation from the previous year that "a controlled deorbit capability must be developed for the ISS as soon as practicable."

While the aging hardware points to the steadily approaching end of the ISS' life and the need for planning a controlled deorbit, "it must also be noted that a critical or catastrophic failure could occur with little or no warning, necessitating an immediate safe disposal of the damaged station," the ASAP pointed out.

"The urgency of defining a deorbit plan, first highlighted in 2012, is now even more pressing given the steadily approaching end-of-life date," the ASAP stated in its most recent report to NASA.

Related: The International Space Station will eventually die by fire

Best option

Last June, NASA announced it had picked SpaceX to design the United States Deorbit Vehicle (USDV), with a contract worth up to $843 million. A space agency white paper on intentionally deorbiting the ISS concluded that "using a U.S.-developed deorbit vehicle, with a final target in a remote part of the ocean, is the best option for station's end of life."

Given NASA's selection of SpaceX to take down the whole structure at once, "it seems the procedural path is already laid out," said Leonard Schulz, a researcher at the Technische Universität Braunschweig's Institute of Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany.

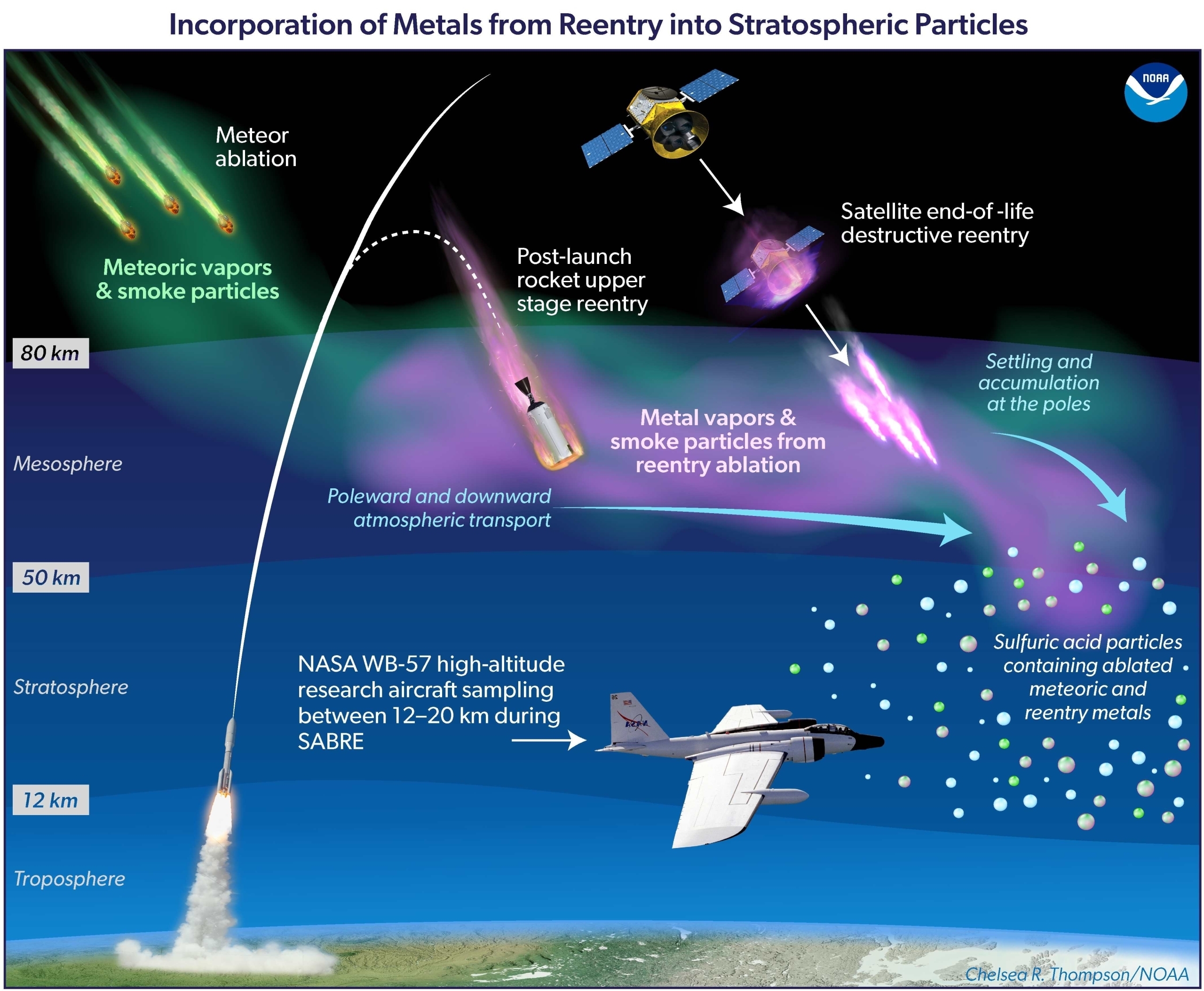

"Considering the large mass of 450 tons — half of human made reentry mass into the atmosphere in 2019, a third of the reentry mass of 2023 — it only enhances the atmosphere problem induced by reentry," Schulz told Space.com. "We'll probably take a look in the future at what this reentry could bring to the atmosphere in terms of released substances."

Oceanic and atmospheric pollution

Physicist Luciano Anselmo works at the Space Flight Dynamics Laboratory in the Institute of Information Science and Technologies in Pisa, Italy.

Concerns and complaints about the debris dumped into the oceans by reentering space objects make a lot of sense in principle, Anselmo told Space.com.

"However, in science and technology, quantitative arguments are relevant as well, and reentering space objects are a very minor contributor to ocean pollution," said Anselmo. Since the start of the space age, the mass reentered from orbit and dispersed on land, oceans and the atmosphere is on the order of several tens of thousands of metric tons, he said — less than the mass of a single battleship sunk during World War II.

"And even the ISS, with just around 400 [metric] tons, would be negligible compared to the mass of all the ships and cargo sunk every year, not to mention all other forms of marine waste dumping and pollution," Anselmo said.

Putting it in relative quantitative terms, orbital reentries — including that of the ISS, and possibly space launches as well — are not yet a significant source of oceanic pollution compared to other anthropogenic activities and natural phenomena, added Anselmo.

"However, this can no longer be said for the upper atmosphere, where the impact of space launches and reentries is probably becoming significant, and whose possible consequences are not yet fully assessed," Anselmo advised.

Related: Can we solve the satellite air pollution problem? Here are 4 possible fixes

Controlled dumping

Meanwhile, there are others evaluating the deep-sixing of the ISS. For example, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's Office of Water is looking into the complex issue.

Advocacy groups seeking pathways to protect our watery world, such as the Ocean Conservancy, have also expressed concern about the use of ocean waters as a dumping ground for all manner of human leftovers, be it plastics, tires, radioactive waste or space junk.

Another voice in the ISS deorbit discussion is David Santillo, senior scientist for Greenpeace International at the University of Exeter's Greenpeace Research Laboratories in the United Kingdom.

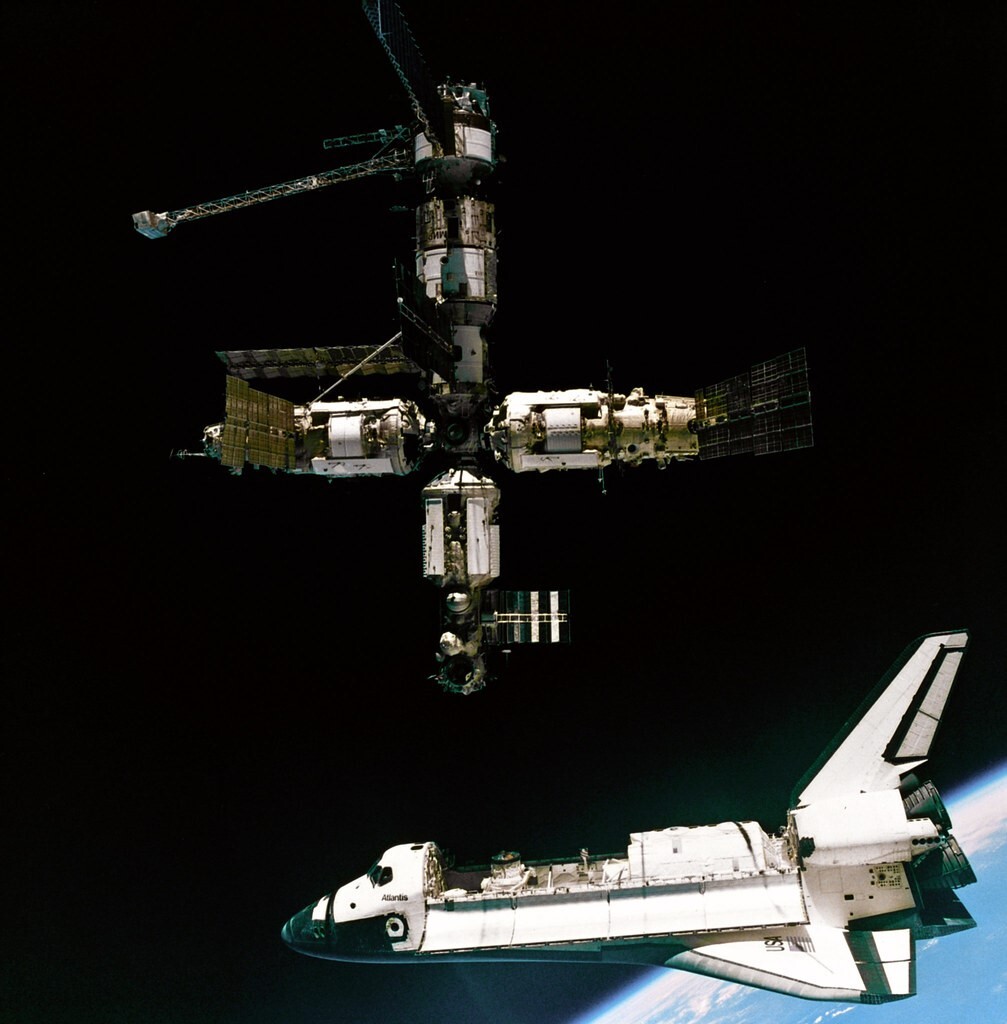

Santillo told Space.com that Greenpeace has a long-standing interest in the dumping of space hardware over Earth's oceans. That engagement harkens back to the deorbiting of Russia's Mir space station in 2001. Controlled reentry of the 130-ton Mir took place over the South Pacific Ocean, near Nadi, Fiji.

Missing legal framework

"As things stand, there is no international legal framework looking at this, which is why we raised the issue all those years ago in relation to Mir, and why we have followed up since," Santillo said.

Santillo suggested that the London Convention and London Protocol, a global convention output to protect the marine environment from human activities, could be a logical place to take the ISS deorbiting issues up and perhaps initiate rule-setting procedures. It could provide some consistency of approach internationally, Santillo said, "but so far there are no specific provisions in place, and it will take some years yet to get there, if we can even get agreement on such a way forward."

But as time goes on and interest in how to safely kill off the ISS grows, more organizations are likely to flag the emerging issue of sea disposal of jettisoned space hardware.

Somebody is going to be unhappy

"Clearly, these folks are more worried about the ocean environment than the space environment, which is fair, but there are few options, with uncontrolled reentry being the worst," said Darren McKnight, senior technical fellow at LeoLabs, a company that monitors activity in space to reveal threats to safety and security.

"If no one will pay to keep the ISS in orbit, where if it cannot maneuver [it] would be a sitting duck for potential collisions, then controlled versus uncontrolled reentry is the question," McKnight said.

If you got creative, McKnight pointed out, you could take the ISS apart and bring it down in pieces, a very expensive proposition. Or, package it up and send it to either a higher Earth orbit or an escape trajectory away from our planet, either of which would also be very expensive, he said.

"I'm a bit concerned that this issue is not about the existing ISS but about future very large space stations. Further, there is ongoing 'concern' about mass that gets vaporized upon reentry. Some people are concerned that we should try to not have objects disintegrate in orbit; we should try to have them survive to reentry," McKnight said.

"So, clearly somebody is going to be unhappy," he concluded.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.