James Webb telescope uncovers massive 'grand design' spiral galaxy in the early universe — and scientists can't explain how it got so big, so fast

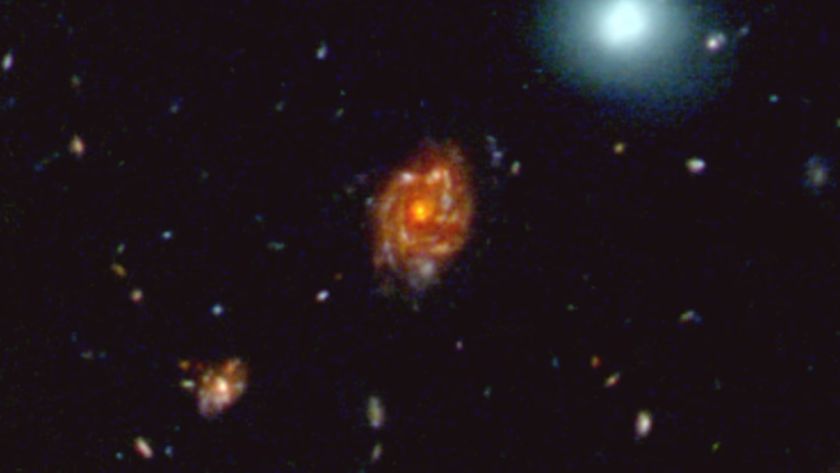

Galaxies in the early universe tend to be clumpy, but the new JWST discovery of a "grand design" spiral galaxy just 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang has scientists stumped.

Researchers just found an unexpected galaxy using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The large swirl of stars is known as a grand-design spiral galaxy, and its exceptionally advanced age could change what we know about galaxy formation.

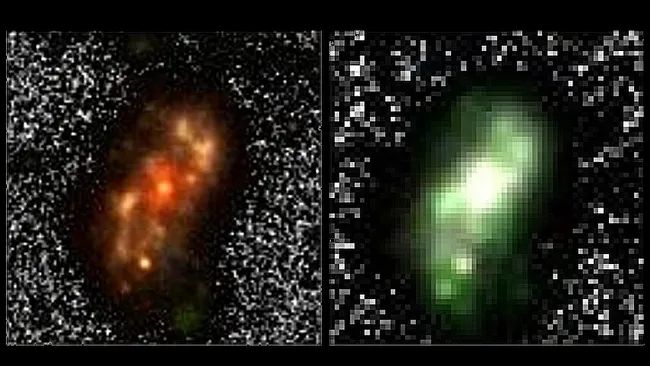

Generally, the older a galaxy is, the farther away it is from us. Scientists can gauge the age and distance of galaxies through something called redshift — a phenomenon that occurs when light shifts to lower-frequency, redder wavelengths as it crosses large stretches of space. This happens for a couple of reasons; first, because the universe is expanding, older stars naturally end up further away. And second, because red is the longest wavelength in the visible spectrum of light, stars that are very far away tend to appear redder, having a higher redshift. JWST is designed to peer deeply into the red and infrared spectrum, allowing it to see old, distant galaxies more clearly than any previous telescope.

But spiral galaxies tend to be on the younger side, making the newly-discovered galaxy, designated A2744-GDSp-z4, an outlier. Grand-design galaxies like A2744-GDSp-z4 are characterized by their two well-defined spiral arms. Very few have ever been found with a redshift above 3.0 — meaning their light has been traveling for nearly 11.5 billion years, according to the Las Cumbres Observatory

The newfound galaxy, meanwhile, has a redshift of 4.03, meaning the light JWST detected was emitted more than 12 billion years ago. According to the researchers who discovered it, that means A2744-GDSp-z4 came together when the universe was only about 1.5 billion years old — and it appears to have formed very rapidly. Given its estimated star formation rate, it accrued a mass of about 10 billion solar masses in just a few hundred million years.

Related: James Webb telescope confirms we have no idea why the universe is growing the way it is

This flies in the face of how scientists think spiral galaxies usually form.

"The rarity of high redshift spirals might be a consequence of galaxies being dynamically hot at those early epochs," the researchers, led by Rashi Jain at the National Center for Radio Astrophysics in India, wrote in the new study. "Dynamically hot systems tend to form clumpy structures," rather than highly ordered spirals, the researchers added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team theorizes that A2744-GDSp-z4's formation may have been driven by the presence of a stellar bar — gassy structures found in a majority of galaxies, which fuel starbirth and channel gas between the inner and outer regions of a galaxy, contributing to the galaxy's size and shape. The ancient spiral could also have formed through the merger of two smaller galaxies, though this seems less likely given its orderly structure, the researchers wrote.

The findings were published Dec. 9 on the preprint database arXiv. The study has not yet been peer-reviewed.

This story as provided by Space.com's sister site Live Science. Read the original.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.