Vanguard 1 is the oldest satellite orbiting Earth. Scientists want to bring it home after 67 years

"It would be a record for retrieving an exposed spacecraft."

Decades ago during the heady space race rivalry between the former Soviet Union and the United States, the entire world experienced the Sputnik moment when the first artificial satellite orbited the Earth.

Sputnik 1's liftoff on Oct. 4, 1957 sparked worries in the U.S., made all the more vexing by the embarrassing and humiliating failure later that year of America's first satellite launch when the U.S. Navy's Vanguard rocket went "kaputnik" as the booster toppled over and exploded.

An emotional rescue for America came via the first U.S. artificial satellite. Explorer 1 was boosted into space by the Army on Jan. 31, 1958. Nevertheless, despite setbacks, Vanguard 1 did reach orbit on March 17, 1958 as the second U.S. satellite.

And guess what? While Explorer 1 reentered Earth's atmosphere in 1970, the Naval Research Laboratory's (NRL) Vanguard 1 microsatellite is still up there. It just celebrated 67 years of circuiting our planet.

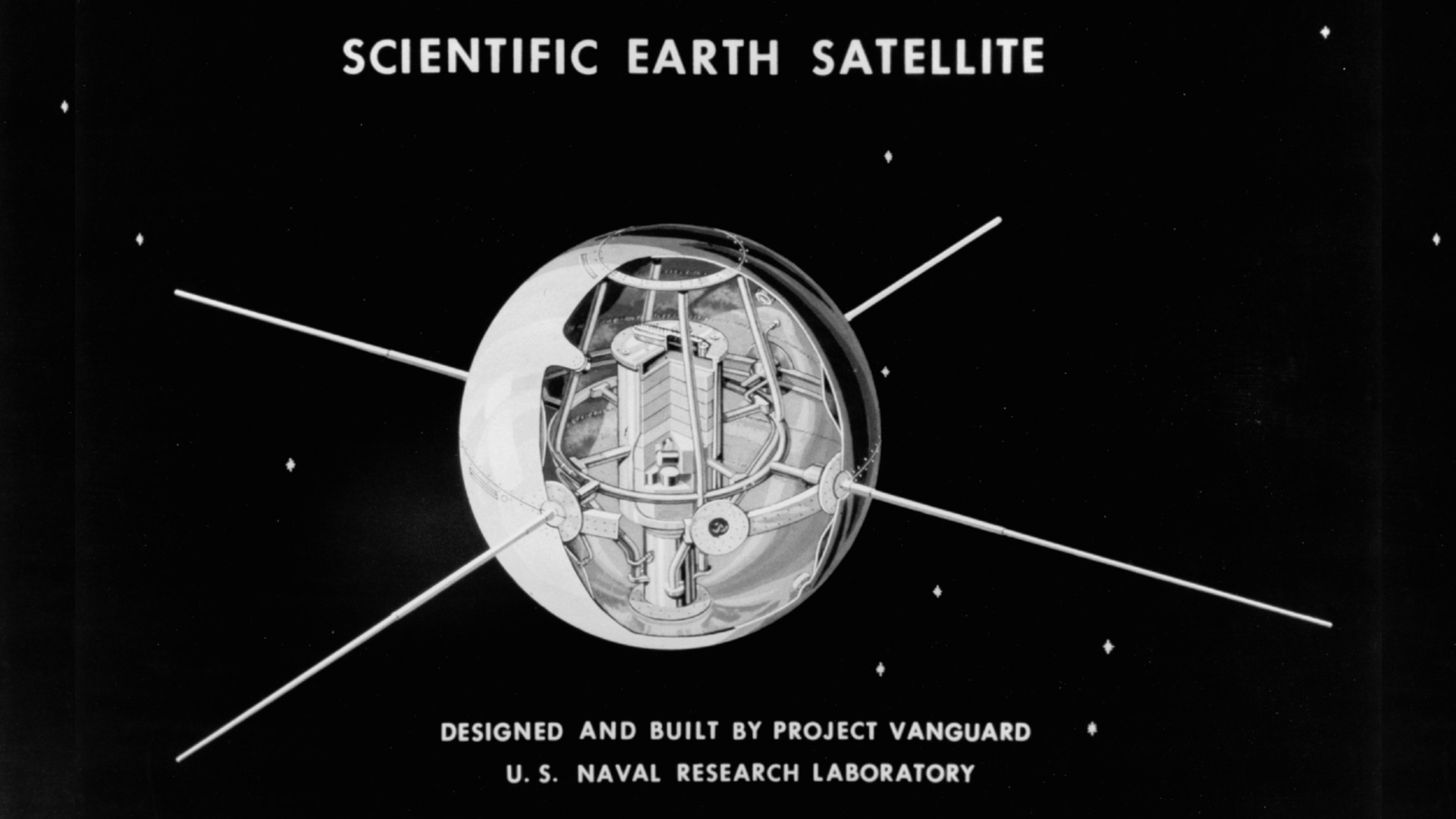

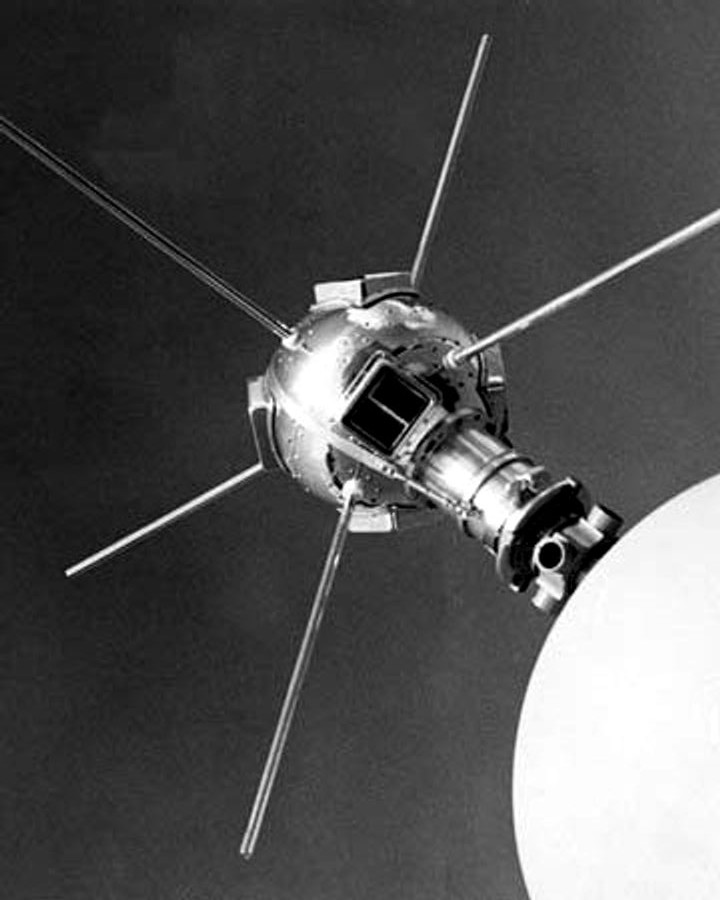

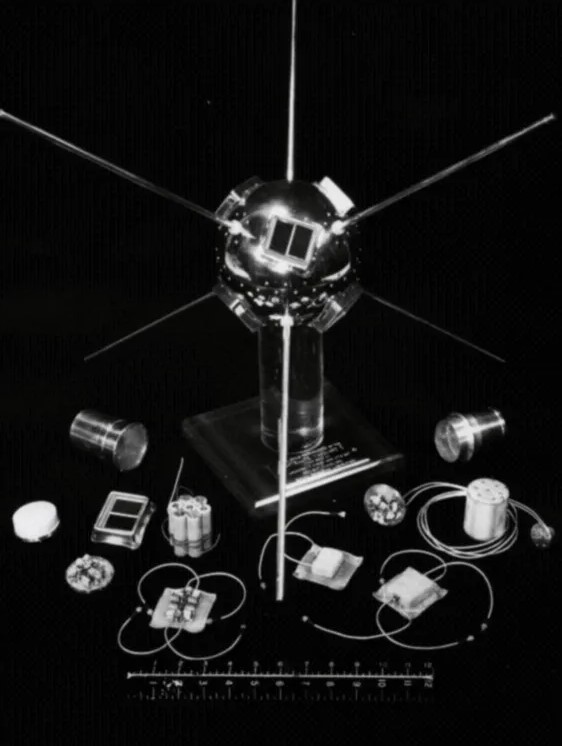

NRL remains the owner of the object and the developer of its technology. Vanguard 1 was the first satellite to generate power using solar cells.

Today, the satellite is in an elliptical orbit with its perigee roughly at 410 miles (660 kilometers), swinging out to an apogee of approximately 2,375 miles (3,822 kilometers) from Earth, with a 34.25 degree inclination.

Possible retrieval?

A team that includes aerospace engineers, historians and writers recently proposed "how-to" options for an up-close look and possible retrieval of Vanguard 1.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Snagging the oldest orbiting satellite of any nation would not be easy, but is worthy of further study, the team noted last year at a science and technology conference sponsored by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.

Vanguard 1 is a time capsule of the Space Age, the study group explained. The notion of recovery offered by the team was their own, not necessarily reflecting the view of their organization, Booz Allen Hamilton, a leading advanced technology company that deals with an array of critical defense, civil, and national security issues.

Silent satellite

Matt Bille, a Booz Allen aerospace research analyst in Colorado Springs, Colorado led the Vanguard 1 salvage scenario research.

"We're not the first people to have the idea, and we hope we won't be the last," Bille told Space.com. "But we'll have to wait and see whether any entities with the needed capability decide the value to them is worth the expenditure."

As one would expect, the elder satellite is no longer transmitting, but its whereabouts are known.

"Yes, the satellite went silent in 1964," Bille said, "when the output of the solar cells dropped below the power needed to run the transmitter." Publicly available tracking data show Vanguard 1's location and orbit, information that could be used to target higher-resolution sensors, he added.

Those sensors might determine whether the satellite is intact and confirm its spinning or tumbling status, said Bille.

Exposed spacecraft

If Vanguard 1 is recovered and hauled back to Earth, how much could be gleaned from up-close inspection?

"Our research indicated possible interest in the condition of the solar cells, batteries, and metals, along with the record of micrometeorite or debris strikes over such a long time," Bille responded. "It would be a record for retrieving an exposed spacecraft."

Bille and colleagues have scoped out options for missions and payloads using technology that could safely inspect, and, if desirable, retrieve the satellite for study, then put on display as astronautical archaeology.

Vanguard 1 could be placed into a lower orbit for retrieval, for instance, or taken to the International Space Station to be repackaged for a ride to Earth. After study, this veteran of space and time would make for a nifty exhibit at the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum.

Handle with care

An as-yet-unidentified lead organization could serve as the Vanguard Mission Authority (VMA), the study team explains. The overall mission would be split into two phases: Firstly, imaging of Vanguard 1 to find out its condition prior to a retrieval decision. Given a go, then the actual recovery of the satellite would proceed.

But there's a major challenge of snuggling up close to the three pound (1.46-kilogram) Vanguard 1. It is a small-sized satellite, a 15-centimeter aluminum sphere with a 91-centimeter antenna span. It would be a delicate, 'handle with care' state of affairs.

As suggested by the study group, perhaps a private funder with historical or philanthropic interests could foot the retrieval bill. Keep in mind that entrepreneur Jared Isaacman made self-funded space treks using a SpaceX capsule, even taking the first civilian space walk. He has also proposed a mission to saunter up to the Hubble Space Telescope.

Then there's well-heeled Jeff Bezos of Blue Origin that backed the retrieval of Apollo-program Saturn V engines from the Atlantic for museum displays.

Learning opportunity

Bringing Vanguard 1 home is appealing for several reasons.

The ability to develop and demonstrate industry-provided space repositioning services is one.

"For materials engineers and space historians, it would be a learning opportunity like no other," Bille and study members argue. "Retrieving Vanguard 1 would be a challenge, but an achievable and invaluable step forward for the entire U.S. space community."

Similar in view is Bill Raynor, the Naval Research Laboratory's associate superintendent of the spacecraft engineering division.

While Vanguard-1 went silent in May 1964, Raynor said that since that time, the satellite's 133-minute orbit has been tracked by a network of optical space surveillance sensors and continues to be of scientific interest to this day.

"The results of the tracking of Vanguard-1's orbit provided much of the early data supporting the discovery and estimation of the Earth's oblateness, similar to a pear-shape," Raynor told Space.com.

If Vanguard 1 was recovered and brought back here to Earth, how much could we glean from its long duration exposure?

"For material and radiation effects scientists and engineers," Raynor added, "it would be an unprecedented opportunity for investigating the effects of long-term space environmental exposure."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.