NASA's new SPHEREx space telescope to launch in February — it can do what the JWST can't

"We are literally mapping the entire celestial sky in 102 infrared colors for the first time in humanity's history."

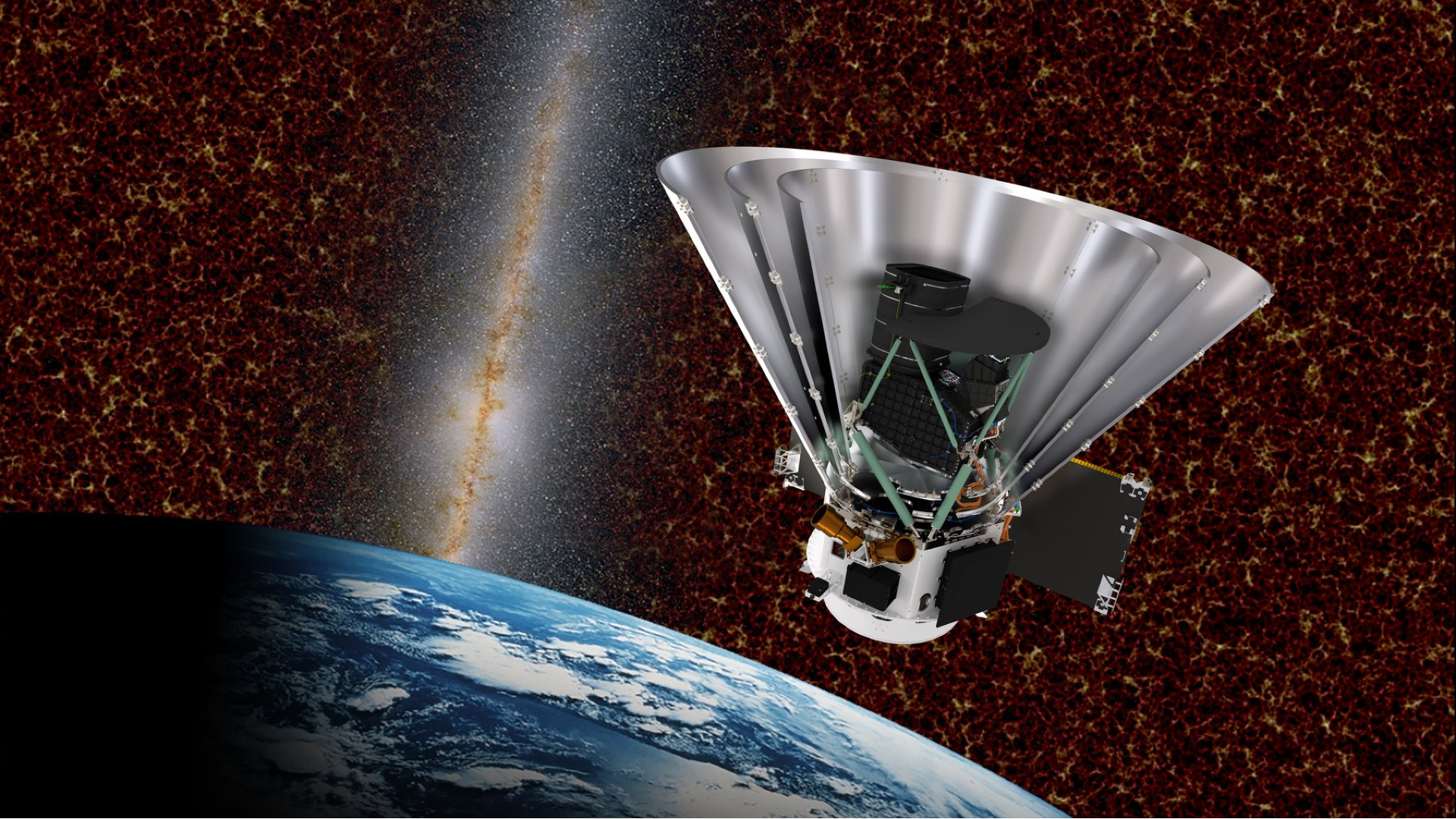

In late February, if all goes to plan, a new character will enter NASA's space telescope epic. It's an eggshell white, conical probe named SPHEREx, which (get ready for a mouthful) stands for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization and Ices Explorer. And, because it works with infrared light, SPHEREx is meant to reveal things even the trailblazing James Webb Space Telescope cannot.

"Taking a snapshot with JWST is like taking a picture of a person," Shawn Domagal-Goldman, acting director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters, told reporters on Jan. 31. "What SPHEREx and other survey missions can do is almost like going into panorama mode, when you want to catch a big group of people and the things standing behind or around them."

Launch is presently scheduled for no earlier than Feb. 27 aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket — and SPHEREx won't be the only payload. As part of NASA's Launch Services Program, which connects space missions with appropriate commercial launch vehicles, SPHEREx will share its ride with the agency's PUNCH (Polarimeter to Unify the Corona and Heliosphere) mission, a constellation of four little satellites meant to study the sun. The duo will lift off from Launch Complex 4E at Vandenberg Space Force Base in Central California.

"This is the third launch of this reusable booster, which was previously flown on the Transporter 12 mission on January 14," Cesar Marin, SPHEREx integration engineer for the Launch Services Program at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, said during the briefing, referring to the Falcon 9's first stage. "The booster will be applying its phenomenal capacity of returning once again to land in zone four at Vandenberg Space Force Base about eight minutes after launch."

The promise of SPHEREx

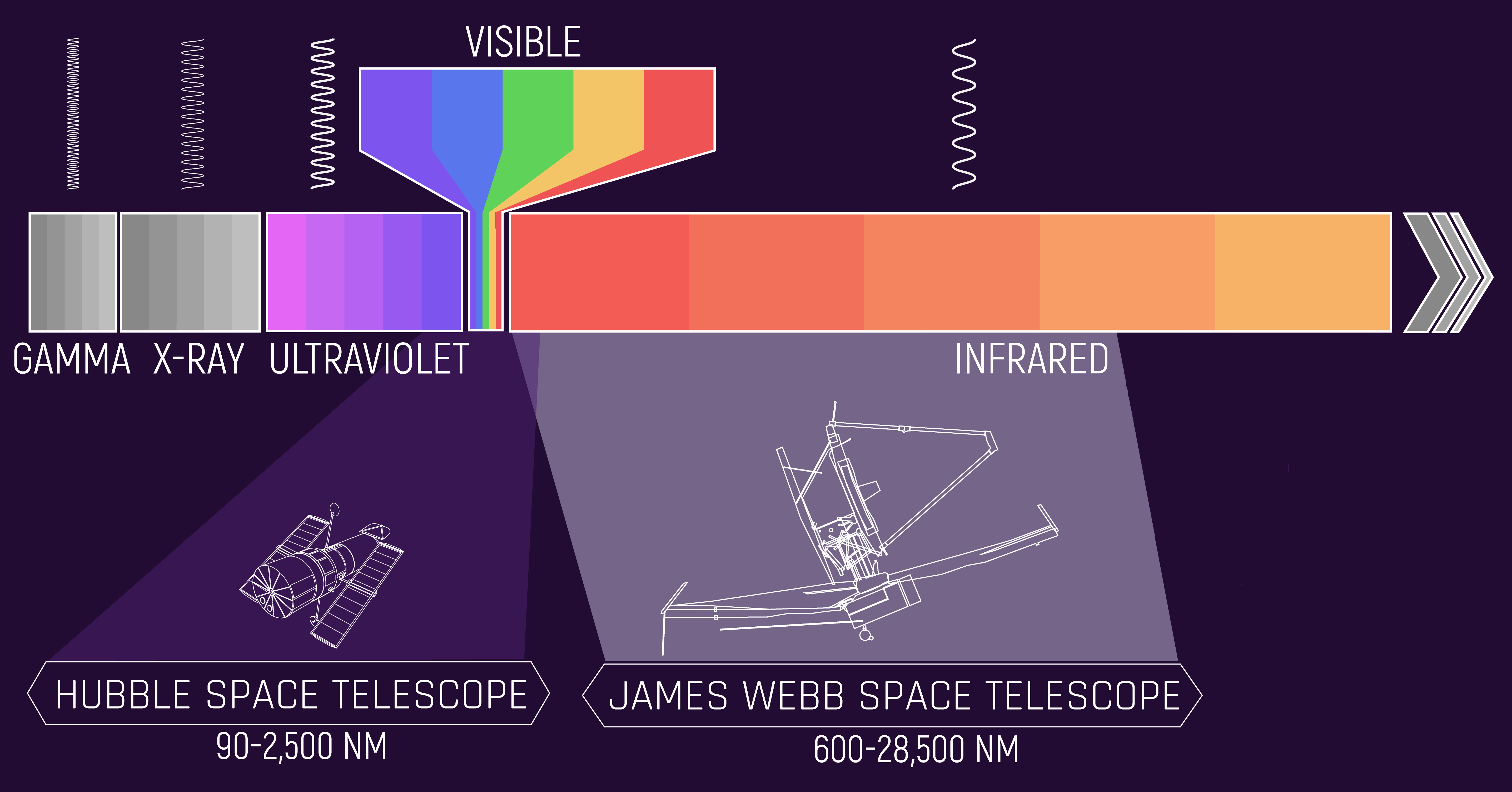

Over two years — unless NASA decides to extend the mission — SPHEREx will map the universe while detecting two kinds of cosmic light: optical and infrared.

Optical light is visible to the human eye, and is the specialty of many telescopes including the Hubble Space Telescope, while infrared light is invisible to us and is more akin to a heat signature. Infrared is the James Webb Space Telescope's speciality, and is in fact why the JWST has been so iconic in showing us things in the universe that have remained hidden for so long. It is the universe's infrared light that possesses information about the farthest reaches of space, the stars being born within blankets of dust, and the details of galactic structures that are showing scientists the cosmic equivalent of new colors.

There have indeed been other infrared eyes on the sky — like the now-retired Spitzer Telescope, and even Hubble has some capabilities in this realm — but none really match up to the JWST.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

SPHEREx could, though (in a way).

To be fair, SPHEREx won't rival the JWST's ability to observe highly localized regions of the universe that are confined to the infrared section of the electromagnetic spectrum. However, unlike the JWST, it is an all-sky survey. Whereas the $10 billion JWST is great at observing things like specific nebulas and relatively narrow but tremendously dimensional deep fields, SPHEREx is intended to image the entire sky as seen from Earth.

"We are literally mapping the entire celestial sky in 102 infrared colors for the first time in humanity's history, and we will see that every six months," said Nicky Fox, associate administrator for NASA's Science Mission Directorate. "This has not been done before on this level of color resolution for our old sky maps."

"In terms of all-sky survey missions," Jamie Bock, principal investigator of SPHEREx at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, said during the briefing, "generally, these have been done in photometry, looking at the sky in broad bands and handfuls of broad bands — not this complete spectrum."

The SPHEREx targets

As to what SPHEREx will be searching for? Well, considering the space telescope will be pretty much mapping everything in the sky from its special dawn-dusk sun synchronous orbit that keeps it cool enough to study infrared emissions — the list is endless.

To name a few goals, however, scientists wish to learn about lots of galaxies at various points in their histories to enhance our knowledge of galactic evolution, and they want to peer into the empty space between stars to see if there are any icy organics floating around to trace how life on Earth might have begun.

"Shout out to our team at OSIRIS-REx in the Planetary Division," Domagal-Goldman said. "They pick up that story and then tell how it traverses in our solar system to planets like our home."

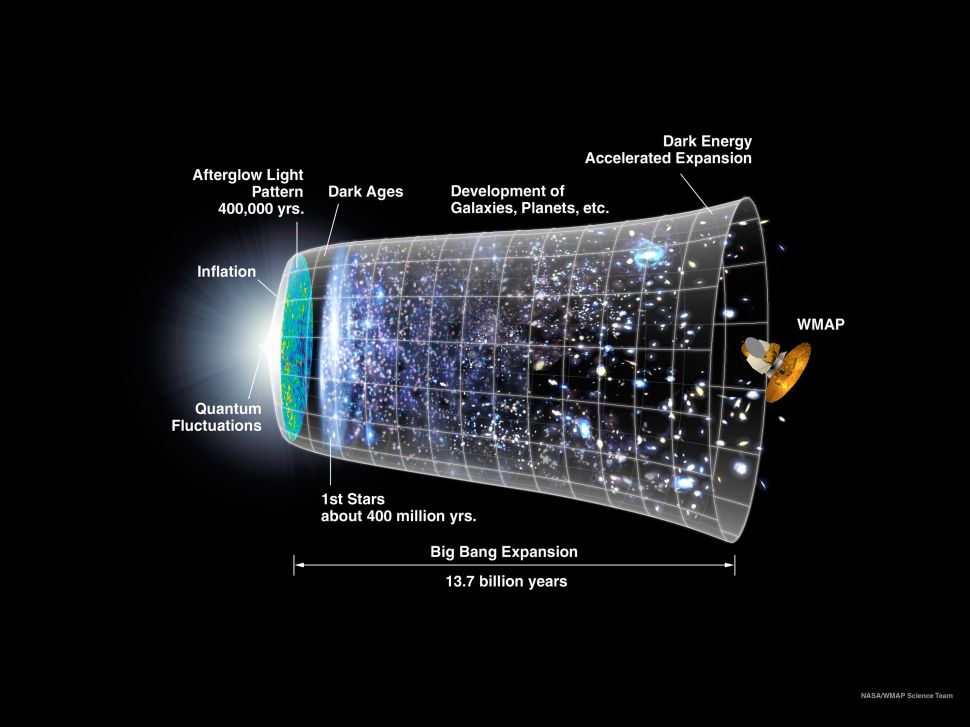

Scientists also hope to capture three-dimensional views of hundreds of millions of galaxies to further our understanding of cosmic inflation —the theory that, moments after it was born, the universe experienced a mind-blowing amount of expansion. It was as though a balloon suddenly inflated.

"Literally a trillionth of a trillionth of a billionth of a second after the Big Bang, the observable universe went through a remarkable expansion," Bock said, "expanding a trillion trillion fold, and that expansion expanded tiny fluctuations smaller than an atom, to enormous cosmological scales that we see today."

"We still don't know what drove inflation or why it happened," he said.

It's usually the case that different space missions benefit one another down the line, but such collaboration seems especially prevalent here. Most obviously, because the JWST is so adept at infrared imaging, it will be tremendously useful for SPHEREx to present JWST scientists with an all-sky infrared map so they'll know what areas to zero in on. And, as mentioned, the OSIRIS-REx asteroid-sampling mission (now known as OSIRIS-APEX after its new asteroid target, the notorious Apophis) is also trying to connect the dots when it comes to organics scattered across space.

We'll also see a major ground-based telescope, the Vera Rubin Observatory, see first light later this year, if all goes according to plan. Rubin will be mapping gigantic sections of the sky as well, though in different wavelengths — but that just means another filter of observations to add onto SPHEREx's maps.

"No single instrument, no one instrument, no single mission can tell us the full story of the cosmos," Domagal-Goldman said. "Those answers to the big questions like that, they come from the power of combined observations from combined observatories."

SPHEREx logistics

"SPHEREx is a testament to doing big science with a small telescope," Beth Fabinsky, deputy project manager of SPHEREx at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said during the briefing.

The team says SPHEREx costs about $488 million (excluding some costs to come) which sounds like a lot, but is rather modest in terms of space mission pricetags. That's especially true when considering what SPHEREx could ultimately offer to our scientific textbooks.

Within this budget, the spacecraft was also meticulously crafted, with attention given to several key aspects of its structure.

"It weighs about 1,100 pounds, so a little less than a grand piano, and uses about 270-300 watts of power — less than a refrigerator," Fabinsky said. "It produces more power than it needs using a thick solar array, very much like one you might have on the roof of your house."

But the most pressing concern when it comes to infrared imaging is that the instrument doing the imaging cannot be exposed to heat because that interferes with the data. "If they are too warm, they will be blinded by their own warm glow," Fabinsky said. Yet unfortunately, in space, you'll find there is one of the hottest possible objects a spacecraft can be exposed to: the sun.

That's why SPHEREx's specific orbit was chosen to keep it away from sunlight, as briefly discussed; this was also a big part of the James Webb Space Telescope's construction and placement. The JWST is also in a location designed to shield it from the sun's warmth at all times, known as Lagrange Point 2.

"We have three concentric cone-shaped photon shields," Fabinsky said, explaining more about how the team plans to keep SPHEREx at appropriately frigid temperatures. "They protect the instrument enclosed in the center from sunlight and Earthshine together with three curved plates at the bottom of the payload called the V-groove radiator. They help radiate heat away from the warm spacecraft beneath the payload."

Once SPHEREx is safely in space, fully deployed, and correctly booted up, the team will begin the effort to conduct the mission's first six-month survey of the sky. "The main form of data release is that we put out what we call calibrated spectral images, and those come within two months of observation," Bock said, though he emphasized that there is one specific achievement he's lasered on for the foreseeable future:

"I have to say that the moment I'm looking forward to is once we pop the lid off the telescope and take in our first image — that'll tell us everything's working as expected."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

-

Damon A 102 infrared colors seems very important to them, it was mentioned three times I think. My first thought was, well, damn, I bet Chyna is already racing to build one that can see in 103 colors.Reply -

George² Reply

Since this is a telescope located in space that will not be hindered by the Earth's atmosphere, but only by gas and dust clouds and highly heated plasma winds and particle jets located between the telescope and the observed objects, it is important to choose wavelengths for which these obstacles are permeable, transparent.Damon A said:102 infrared colors seems very important to them, it was mentioned three times I think. My first thought was, well, damn, I bet Chyna is already racing to build one that can see in 103 colors.

As for the question of whether the chosen number of lengths is sufficient and not too large and whether it would be a value around which a competition would arise... Well, I don't know, but in the past and today there have been competitions with stupid reasons. -

Icepilot Reply

"the cosmic equivalent of new colors." - I like a metaphor as well as anyone, but this is supposed to be science.Admin said:SPHEREx is slated to launch Feb. 27 on a SpaceX rocket. It is meant to map the entire night sky in infrared — something even the JWST can't exactly do.

New NASA space telescope SPHEREx to launch in February — it can do what the JWST can't : Read more

Not "new", hidden. -

billslugg This is all correct, but provides no new information. It writes a headline the body can't cash. My English teacher would have called it "wordy". I was hoping to find out why this scope is better than JWST, like what is it's range and sensitivity?Reply

Also seems to be making up terms. What exactly is "optical light". I have heard "visible light" but never "optical light". Optical light, to me, would be any light, visible to a human or not, that can be brought to a focus. "Visible light" would be light our eyes can see.

The author has a "BA in Philosophy, Physics and Chemistry" and formerly worked as an immunologist. I have a question, how do you get a BA in a scientific field?

A lot of stuff does not add up here.

-----------------------------------------------------------------

The promise of SPHERExOver two years — unless NASA decides to extend the mission — SPHEREx will map the universe while detecting two kinds of cosmic light: optical and infrared.

Optical light is visible to the human eye, and is the specialty of many telescopes including the Hubble Space Telescope, while infrared light is invisible to us and is more akin to a heat signature. Infrared is the James Webb Space Telescope's speciality, and is in fact why the JWST has been so iconic in showing us things in the universe that have remained hidden for so long. It is the universe's infrared light that possesses information about the farthest reaches of space, the stars being born within blankets of dust, and the details of galactic structures that are showing scientists the cosmic equivalent of new colors.

There have indeed been other infrared eyes on the sky — like the now-retired Spitzer Telescope, and even Hubble has some capabilities in this realm — but none really match up to the JWST. -

George² Reply

When comparing telescopes with different purposes, it is natural that each of them has advantages related to its specific work. Mapping the universe is not a primary, or even a part of the intended activity of the Webb Telescope, so it does not have a wide-angle lens with which to capture large areas of the celestial sphere at once.billslugg said:wordy". I was hoping to find out why this scope is better than JWST, like what is it's range and sensitivity? -

billslugg Reply

Yes, I already knew all of that based on the first part of the article. The last part promised to give me specifics and it didn't. I wanted to know how many square degrees it can see and in what wavelengths, how sensitive and how that differed from JWST, all I got was mush.George² said:When comparing telescopes with different purposes, it is natural that each of them has advantages related to its specific work. Mapping the universe is not a primary, or even a part of the intended activity of the Webb Telescope, so it does not have a wide-angle lens with which to capture large areas of the celestial sphere at once. -

George² Reply

11°x3.5° field of view for SPHEREx. Make your math, please. ;)billslugg said:Yes, I already knew all of that based on the first part of the article. The last part promised to give me specifics and it didn't. I wanted to know how many square degrees it can see and in what wavelengths, how sensitive and how that differed from JWST, all I got was mush. -

Classical Motion I think it is different and will gives us much more information. My completely uninformed opinion is that up to now, most of our star observations have been skinny. Until WEBB. But WEBB is a pin point seeker.Reply

We have looked in all directions, but we haven’t listened for all the sounds. Only certain tones.

These selected red tones, will give us a peek of the EM bandwidth of space.

A full bandwidth RX, like WEBB for a omni scan would be very expensive.

But selected cheap detectors for certain slots of that spread, can give us a quick glimpse. Of what might be there.

Much of this bandwidth has to be done out in cold space. And L2 is perfect cover from the sun.

This is what I harvest from the article. It doesn’t tug on me that much for further interest. We now have data over decades in age that no one has seen yet. Maybe A.I. will help us catch up.

We should hear more about it in the future. With a better explanation of it’s capabilities. Especially if something new shows up. Like a huge warm spot.

When are we gong to make our instruments refuel-able? When it dies can we exit L2? Or will we have L2 junk?

What are the environment effects? For the next L2 residents. Our L points should be protected. A HOA. No junkers. -

Moonwatcher Reply

In all the articles about SPHEREx and PUNCH, none of them mention what orbit they will be launching into. Seems strange to launch such lightweight space telescopes on a Falcon 9 that can haul up 40,000 lbs. easily into low Earth orbit, but I guess it is the most cost-effective launch vehicle around today. Still, I'd like to know the inclination and orbital altitude these are set for.Admin said:SPHEREx is slated to launch Feb. 27 on a SpaceX rocket. It is meant to map the entire night sky in infrared — something even the JWST can't exactly do.

New NASA space telescope SPHEREx to launch in February — it can do what the JWST can't : Read more -

billslugg You can't even find the orbit and inclination on NASA website by cursory examination. Wiki has it right on the first page as always. SPHEREx will be 700 km in altitude, 97° inclination.Reply