'Tragedy of the commons' in space: We need to act now to prevent an orbital debris crisis, scientists say

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Humanity needs to start addressing the growing space junk problem now, before it gets out of hand, scientists stress.

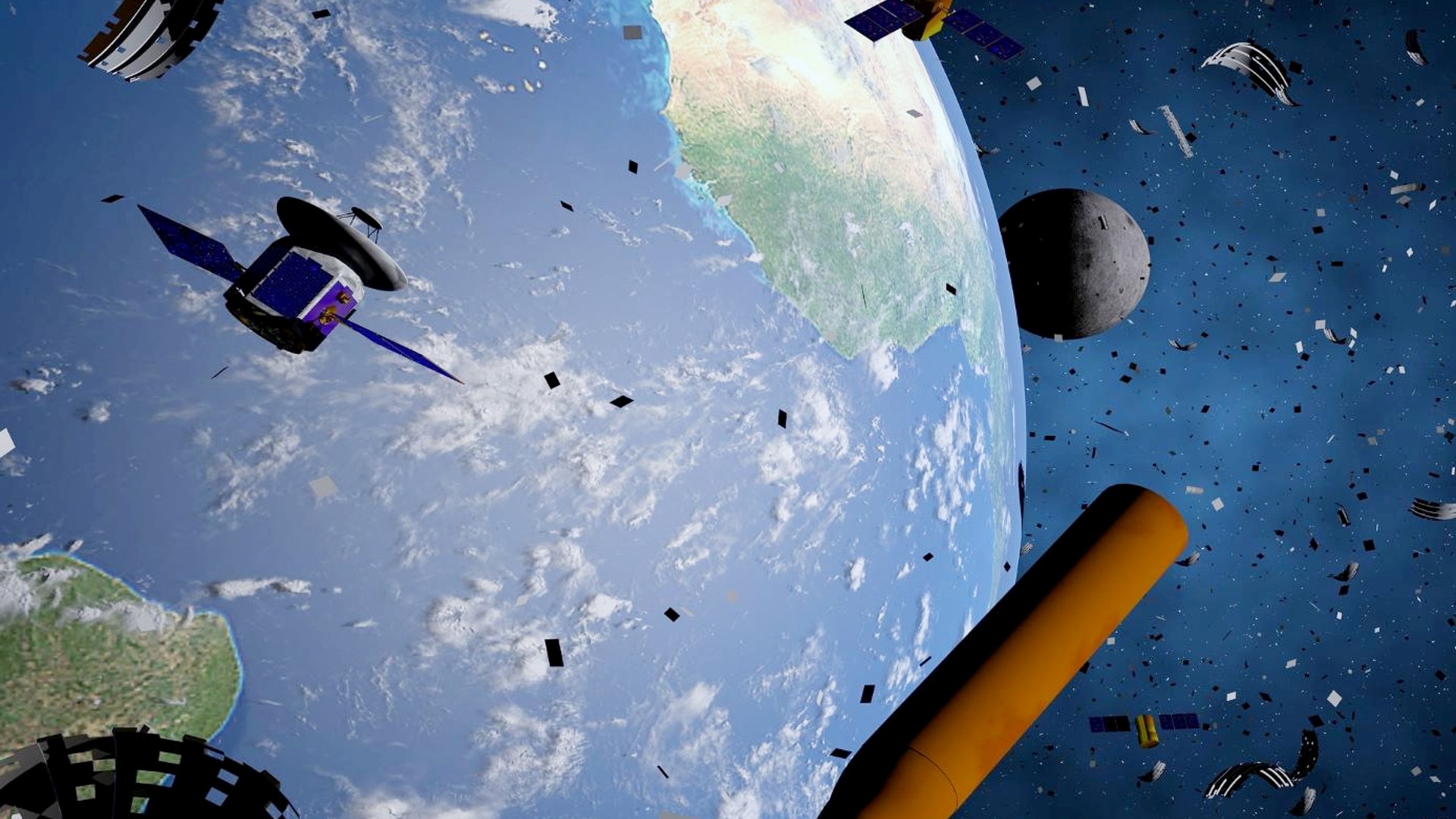

Earth orbit is getting more and more crowded, with both active satellites and pieces of debris. There's so much stuff up there that it's far from alarmist to start worrying about the Kessler syndrome, a nightmare scenario in which a collision or two leads to many more, vastly increasing the amount of junk circling our planet.

“We have to get serious about this and recognize that, unless we do something, we are in imminent danger of making a whole part of our Earth environment unusable," Dan Baker, director of the Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics at the University of Colorado, Boulder (UC-Boulder), said in a panel Wednesday (Dec. 11) at the 2024 meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in Washington, D.C.

Earth orbit harbors more than 10,200 active satellites, according to the European Space Agency (ESA). Most of these spacecraft are in low Earth orbit (LEO), a shell that lies roughly 125 miles to 1,250 miles (200 to 2,000 kilometers) above our planet.

Related: 7 wild ideas to clean up space junk

Most of those LEO satellites — about 6,800 of them — belong to a single constellation: SpaceX's Starlink broadband network.

These numbers are growing all the time, and the tally could soon get mind-bogglingly high. SpaceX, for example, wants the Starlink network to eventually harbor more than 40,000 spacecraft.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other players aim to build their own broadband constellations in LEO as well. China has begun building out its Qianfan ("Thousand Sails") megaconstellation, which will feature about 14,000 satellites if all goes according to plan. In addition, Amazon intends to assemble its own 3,200-satellite LEO broadband network, called Project Kuiper.

And these are just the active satellites; the amount of junk in Earth orbit is much higher. For instance, ESA estimates that there are about 40,500 debris objects at least 4 inches (10 centimeters) wide whizzing around our planet. The space debris population includes another 1.1 million pieces between 0.4 inches and 4 inches (1 to 10 cm) wide, and 130 million in the 1-millimeter to 0.4-inch range.

Even these tiny fragments can do considerable damage to a satellite or other spacecraft, considering how fast orbiting objects move. At the International Space Station's average altitude of 250 miles (400 km), for instance, orbital velocity is about 17,500 mph (28,160 kph).

These shards are too small to track using ground-based radars. This is a shame, scientists say — and not just because the slivers are potentially dangerous.

"If the Kessler syndrome starts to happen and we start to see a sort of cascade of collisions, we're going to see it in the smallest grains first," space plasma physicist David Malaspina, an assistant professor at UC-Boulder, said during Wednesday's AGU panel. "These are our canary in the coal mine."

It's tough to quantify the Kessler Syndrome risk, Malaspina and other panelists said, because the orbital environment is dynamic on several different levels.

For starters, the orbital population is growing all the time, as rockets launch more and more satellites to space, so calculations tend to become obsolete almost as soon as they are made. And Earth's atmosphere, which drags LEO satellites down slowly over time via friction, changes as well — expanding, for example, in response to increased solar activity.

As you might expect, these satellites are having more and more close encounters with each other and with pieces of debris. Indeed, there are about 1,000 collision warnings per day on average in LEO, according to Thomas Berger, director of UC-Boulder's Space Weather Technology Research and Education Center.

"So, it's getting difficult for satellite operators to determine which of these warnings is important and which they have to pay attention to," Berger said during Wednesday's AGU panel.

The vast majority of these warnings involve Starlink satellites, which are far from sitting ducks. These spacecraft use onboard software to spot possibly worrisome encounters and perform evasive maneuvers if needed.

But not every satellite that reaches orbit is so capable; there are no globally enforceable rules that mandate responsible behavior by satellite operators. This regulation vacuum is leading to a "tragedy of the commons" situation, according to Baker.

"Stated simply, the tragedy of the commons is that individuals acting rationally and individually according to their own self interest will deplete a shared resource, even if this is contrary to the best interests of the group," he said. "And I believe that we are watching the tragedy of the commons play out in low Earth orbit right before our eyes."

Some of the resources being depleted are scientific, Baker stressed, noting that large satellite populations can interfere with observations made by visible-light and radio telescopes. And some are cultural or societal — the everyday person's enjoyment of a dark night sky, for example.

Baker thinks the United States should take the lead in instituting guidelines that could help stave off the Kessler syndrome and the tragedy of the near-Earth commons. There is some progress in this area, he noted, citing the recent introduction of the bipartisan Orbital Sustainability Act (ORBITS) in Congress.

"I think it begins at home, and I believe that we all have to play our role," Baker said.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.