Massive star explosions may have triggered two mass extinctions in Earth's past: 'It would be terrifying.'

Deaths of nearby massive stars may have played a significant role in triggering at least two mass extinction events in Earth's history, according to new research.

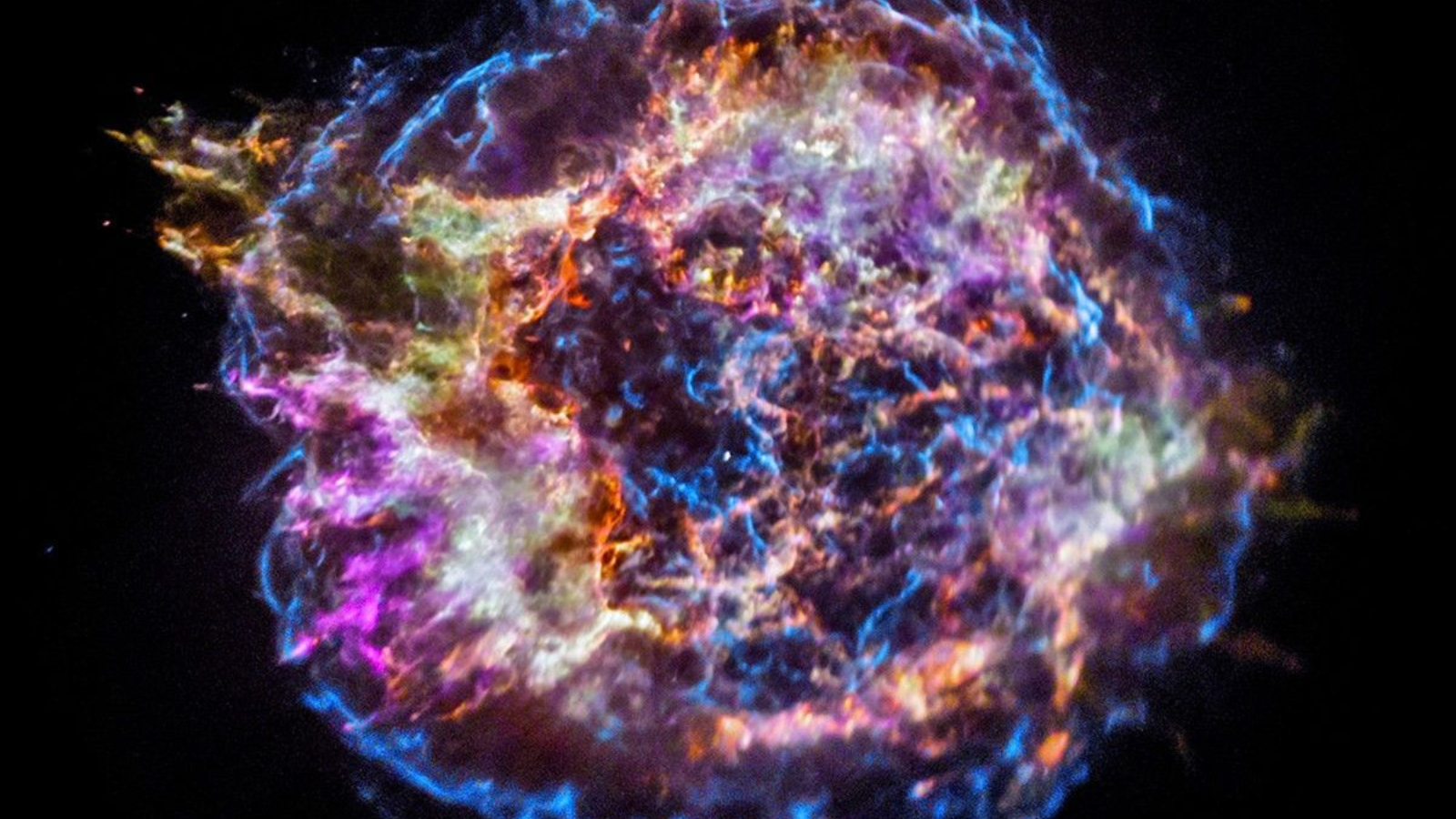

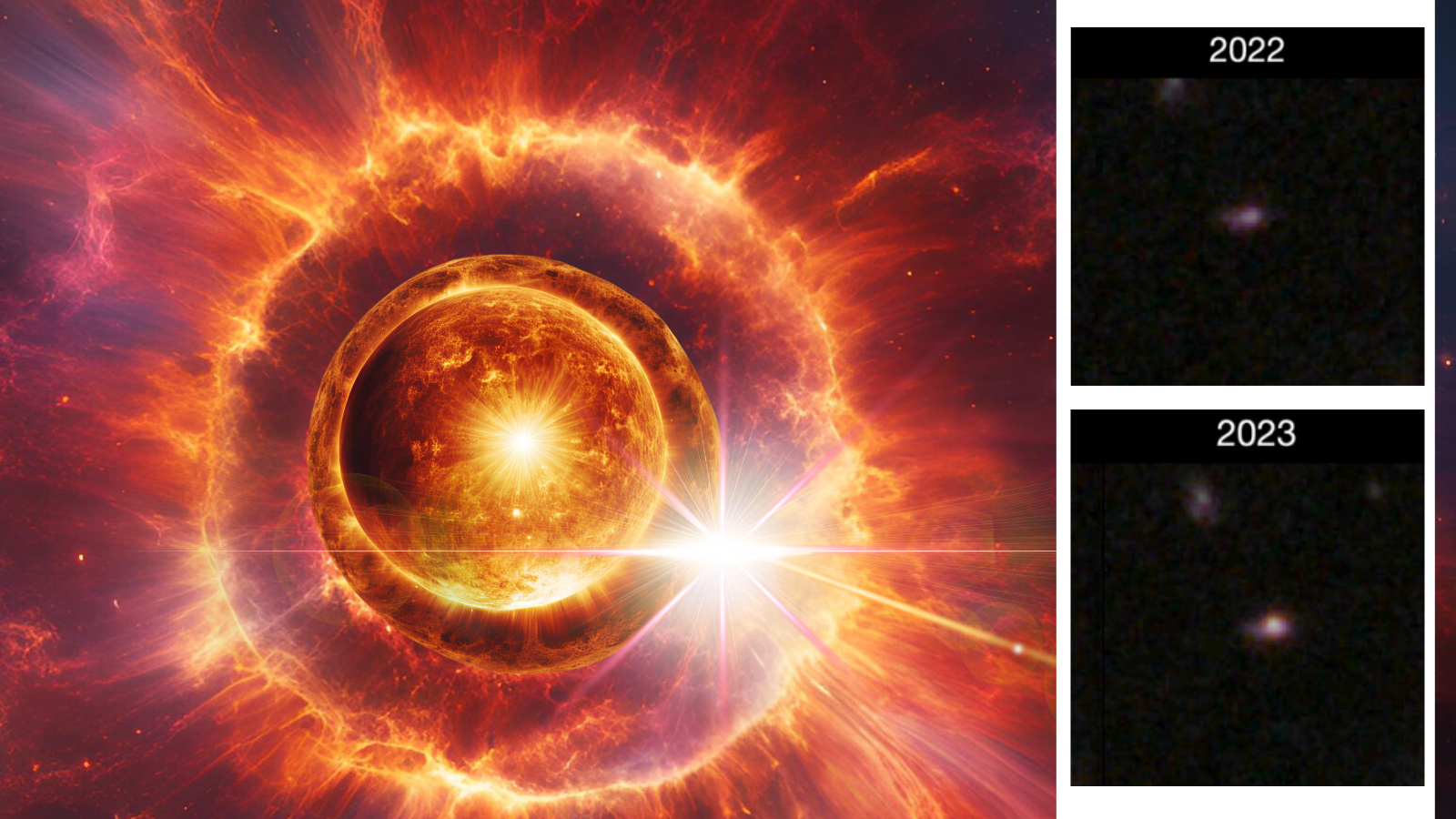

The explosive supernova deaths of nearby massive stars may have played a significant role in triggering at least two mass extinction events in Earth's history, according to new research.

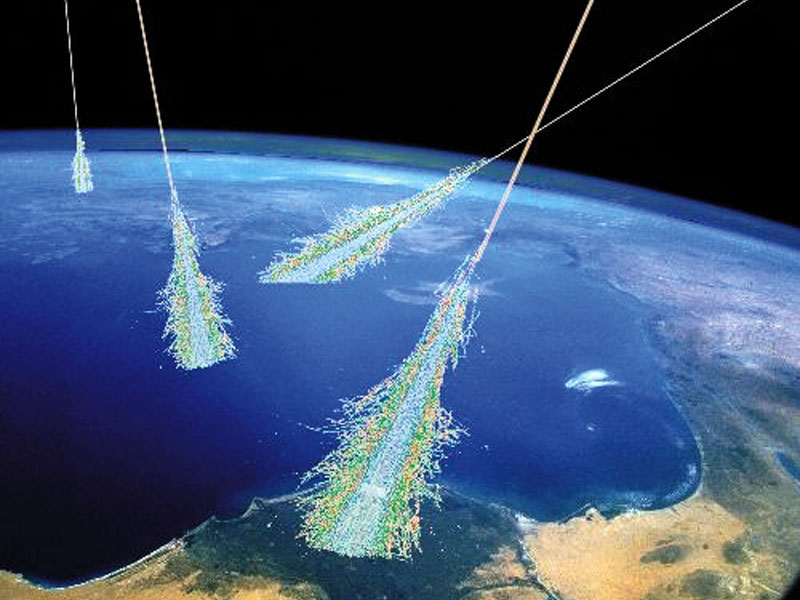

As some of the most energetic phenomena in the universe, supernovae occurring within 60 light-years of Earth could have stripped our planet's atmosphere of its protective ozone layer, exposing life to damaging ultraviolet radiation from the sun, a team of astronomers has discovered.

"A slightly more distant supernova could still cause considerable loss of life, but at this distance, it would be terrifying," study co-author Nick Wright, an astrophysics professor at Keele University in England, told Space.com via email.

Wright and his team used data on the locations of stars collected by the now-retired Gaia satellite to conduct a virtual census of more than 24,000 of the most luminous stars in the universe. They focused on those located within 3,260 light-years of the sun to identify new groups of young, massive stars and reconstruct nearby star formation history.

"It was only once we had completed the work that we realized we could also use the sample to estimate the supernova rate," said Wright. "When we’d done that, we realized it was very close to the rate of unexplained mass extinction events on Earth!"

Supernovas alligning with extinction events

Wright and his team found the timing of supernovae near Earth aligned with two significant mass extinction events on our planet: the late Devonian, a series of mass extinction events that occurred 372 million years ago, and the Ordovician, which occurred 445 million years ago and was the first of the big five mass extinction events in our planet's history.

75% of all species, particularly in the types of fish found in ancient seas and lakes, while the Ordovician event wiped out about 85% of marine species.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It surprised me that the two rates were so similar, which made us want to highlight it," said Wright.

Previous research has found evidence of an influx of the radioactive isotope iron-60 in cosmic dust collected from the Antarctic snow and from the surface of the moon, which can only be attributed to interstellar sources like supernovae. Various studies have linked this flux to the depletion of Earth's ozone layer, caused by cosmic rays showered onto our planet by the stars' explosive deaths.

"Supernovae produce a very high flux of high-energy radiation, which when it reaches the Earth could cause considerable destruction, including breaking apart the ozone molecules that make up the ozone layer," Wright told Space.com.

This ozone depletion, in turn, is thought to have contributed to at least one widespread extinction of marine mammals, seabirds, turtles, and sharks that occurred around 2.6 million years ago. The primary cause behind the Devonian and Ordovician mass extinction events is not fully understood, but both of them have also been linked to the depletion of Earth's ozone layer.

The new study's simulations showed roughly one to two supernovae occur each century in galaxies like the Milky Way.

Within 60 light-years of Earth — the typical distance at which a supernova could potentially cause catastrophic destruction to life on Earth — the rate of supernovae was 2 to 2.5 per billion years. This estimate is in good agreement with the number of unexplained mass extinction events on Earth — specifically, the Devonian and Ordovician extinctions, both of which occurred within the last billion years — raising the possibility that nearby supernovae may have contributed to these events, according to the study.

"It’s worth noting that we don’t have proof that those extinctions were definitely caused by supernovae, only that the rates match up, and therefore, it seems very plausible," Wright said.

These findings are "a great illustration for how massive stars can act as both creators and destructors of life," Alexis Quintana of the University of Alicante in Spain, who led the new study, said in a statement.

"Supernova explosions bring heavy chemical elements into the interstellar medium, which are then used to form new stars and planets," she said. "But if a planet, including the Earth, is located too close to this kind of event, this can have devastating effects."

The team's research was published on Tuesday (March 18) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.