There's a weird, disappearing dark spot on Saturn's moon Enceladus

"After staring at dozens and dozens of image pairs, she found something interesting."

Of all the planets in our solar system, Saturn is by far the mooniest. And that's saying a lot. Sure, we're here in our corner with our single friend, The Moon™, but Neptune wanders the universe with 16 known companions, Uranus boasts 28 of its own, and there are a whopping 95 moons in the Jovian neighborhood. But Saturn? It's in a different league. This ringed world has 146 of these natural satellites. Yet, you may be surprised to know that even with such a lovely Saturnian selection, scientists are mostly pining over just one.

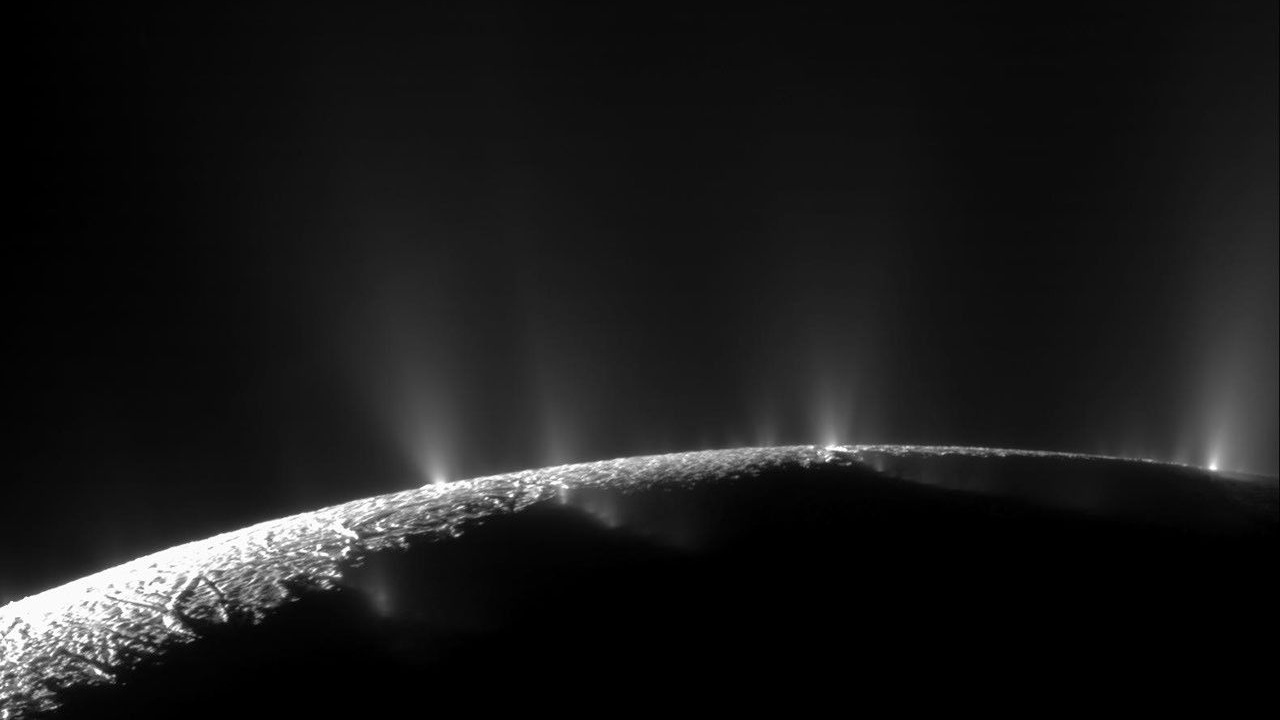

The golden child in Saturn's system is named Enceladus, and it's so special because scientists believe it to be a prime location to search for life beyond Earth. That belief stems from several discoveries made over the years, most obviously the fact that Enceladus seems to have a subsurface ocean that may host molecules known to help produce life as we know it. Better yet, it also appears to have giant plumes of water ice deposits (think icy geysers shooting into space) connected to that ocean, which means spacecraft orbiting the world could theoretically catch evidence of those molecules if they're actually there.

Thus, when studying Enceladus, every detail really matters — which brings us to a new, very strange detail that scientists have their eye on: A weird, disappearing dark spot on this ice-capped moon. No one quite knows what it is yet, but it may tell us something about those plumes that could hold the precious building blocks of life we seek.

This dark spot was one of the intriguing topics of discussion during the 2024 American Geophysical Union meeting in Washington, D.C. — where scientists congregated to search for the final pieces in cosmic puzzles they've been working on all year.

Awe filled the room as Cynthia B. Phillips, a planetary geologist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory who presented the research, went into tremendous detail about how she and her team originally identified the dark spot. It was thanks to her crewmember Leah Sacks, who helped pore through a bulk of data about Enceladus, collected by NASA's Voyager and Cassini missions. The goal of the analysis was to compare images of the same region taken by these spacecraft in order to identify any changes on the moon's surface.

Possible changes could reveal awesome information about geologic activity on the world, but we'll get to that shortly; first let's dive into the mysteries of the dark spot.

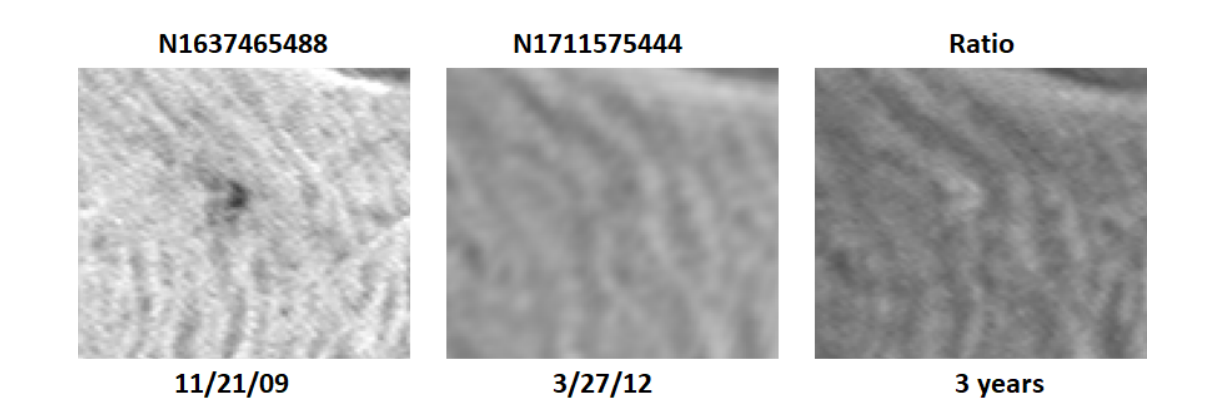

"After staring at dozens and dozens of image pairs — she found something interesting," Phillips said during the conference. "It's a little dark spot; it's about a kilometer across. She spotted it in an image from 2009 and looked again in 2012 and it seemed to be gone."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The dark spot was slowly fading away and getting smaller as the years progressed, and it never became more pronounced again. How weird, and especially so because Enceladus has what's called a high "albedo." That basically means the world is really bright — it's therefore unexpected to find a dark spot on it at all, let alone one that's fading away. But before getting too excited, the scientists made sure to second guess themselves as much as possible to rule out the obvious caveats.

"First our question was," Phillips said, "'well, is it just that in some of these low resolution images, we're not seeing it, but it's really there?'" In short, the answer was a simple "no, probably not." For example, a direct comparison of a 2010 image and a 2011 image shows the dark spot smaller in the 2011 image, even though the 2011 image had a higher resolution.

The next question was: Is this a shadow of some sort? Well, nope. Doesn't look like it.

The team pulled out some images with lighting coming from different directions, and the location of the spot seemed consistent. The researchers even found a sequence of images with the dark spot where the light's angle of incidence (aka, the angle at which light strikes a surface) gets higher and higher. If the spot were a shadow, you'd expect it to become more prominent with a higher incidence angle. This wasn't the case — it still became less distinct as time went on. "We don't think it's topography; we don't think it's just a shadow," Phillips told Space.com.

And it didn't end here — the team also looked at images taken in UV light and color (the latter of which interestingly suggested that the dark spot is a reddish brown, unlike the usual blueish darker areas on other sections of the moon). None of this suggested an easy explanation for the feature.

So, what is it?

"I think the more likely [case] is that it is some kind of a crater," Phillips told Space.com. "And the reason why it's dark is maybe it's a chunk of some kind of dark material that landed on the surface, and you're either seeing some of that impactor left behind, and that's why it has that weird color, or you're seeing that when it impacted, it exposed some kind of bedrock of ice that was a different color."

But for almost every likely and mundane scenario in space research, there tends to exist a rare and exciting one serving as a counterpoint.

"The really cool explanation would be if it was actually coming up from underneath, somehow; if that reddish color was actually a sign of the interior composition of Enceladus," she said. "That's unlikely, but that'd be really interesting."

Still, although we don't know what the dark spot is, Phillips points out that there is indeed something pretty major we can derive from its presence: "'What is it?' I don't know the answer to that — but what I can say is: 'What can we use it for?'"

Remember the plumes

In a nutshell, the researchers think the dark spot appeared to be fading progressively because deposits from those icy Enceladus plumes might have covered it up. "We know the whole surface is covered by plume deposits — like little layers of ice building up over time," Phillips said.

Alas, in theory, this makes a lot of sense. But when you really think about it, there are some outstanding issues here.

For example, the team saw the dark spot fading over just a few years — this would imply that just a few years is long enough for ice plume deposits to create a sheet of ice thick enough to cover such a prominent spot. After all, it's visible from space! Yet, according to various calculations of the dark spot and models of the moon's plumes, Phillips says it should take something like 100 years to create a layer thick enough to cover this kind of spot.

"What this could mean, though, is that the plume deposition model, at least in this location, is an underestimate," she said. "One thing we haven't taken into account, though, is deposition from collisions with E ring particles."

E ring particles refer to the super small water ice particles in Saturn's rings. Potentially, the team reasons, some of those particles could be helping build the sheet covering the dark spot. But the story of this spot's origin and evolution, at this point, is mirrored by the abrupt ending of our story of its discovery.

There are simply too many unanswered questions.

"What would the deposition rate needed to cover the black spot in this time frame indicate about deposition rates? Is the E ring contributing to cover that spot? Is there maybe another mechanism?" Phillips pondered.

"And, you know, what is the black spot?"

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.