'We are close:' SETI astrobiologist Nathalie Cabrol on the search for life

"The missions are telling us that the stuff we're made of is not an accident. It's almost common out there."

A leading astrobiologist melds her passion with the weighty nature of trying to grasp for answers to two key questions: Are we alone in the universe? How did life on Earth begin in the first place?

Nathalie Cabrol's book, "The Secret Life of the Universe: An Astrobiologist's Search for the Origins and Frontiers of Life" (Scribner/Simon & Schuster), released last month, offers an insightful and reflective view of the search for life — a mind-stretching quest not only looking "out there" but also right here on Earth.

Perhaps part of the challenge is that humankind is both the observer and the observation, Cabrol explains. That is, we are life trying to understand itself and its origin. "We are reminded that the universe is both an enigmatic puzzle and a profound mirror reflecting our own existence," Cabrol writes.

The Secret Life of the Universe: An Astrobiologist's Search for the Origins and Frontiers of Life: $25.99 at Amazon SETI's Nathalie Cabrol, one of the world's leading astrobiologists, takes readers on an a mind-bending journey across the universe to investigate humankind's most burning questions: Are we alone in the universe? How did life on Earth begin?

Nathalie Cabrol is a French-American explorer and the director of the Carl Sagan Center for Research at the SETI Institute in Mountain View, California. In an exclusive interview, Space.com discussed with her the new book and the professional odyssey that she has embarked upon.

Space.com: Your book consists of a dozen unique chapters - is there a theme linking them? Perhaps in those subjects you tackled, you were on your own personal journey to help recognize the issues surrounding the are we alone question?

Nathalie Cabrol: The questioning behind every single chapter is that we're looking for something that we don't understand. It's a point of reference that this is us. And that's okay. It doesn't matter that we don't have the answers. Because if we had the answers we wouldn't make the journey.

Space.com: So that journey is one that's open-ended in that we should standby for surprises?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cabrol: The chapters are the journey. Each one helps you see a different perspective, a different angle, shine a different light on a question. I am not necessarily buying the way we're going after life in the universe right now. I'm very vocal about this. But this is where we are and this is what we have. The missions are telling us that the stuff we're made of is not an accident. It's almost common out there. I wanted to share at the same time there are unanswered questions … show there might be other ways of exploring for life.

Space.com: You write about Mars and the long saga of looking for life on the Red Planet. In particular, flagging the Viking Labeled Release (LR) experiment of the 1970s, results that you say today are still deemed inconclusive.

Cabrol: Yes, it's inconclusive and just another acknowledgment that five decades later you have people thinking that it showed that life was there on Mars. We have today evidence those results could be achieved without life and by the environment alone. That [evidence] says we didn't demonstrate that life was there. You have to prove that the environment alone didn't yield those LR results. Environment and life … how do you detangle the two and come up with an unambiguous signature of life? When life is somewhere, you don't have one or the other anymore. You have co-evolution, a mixed thing, a living world.

Nathalie is an astrobiologist and the Director of SETI Institute Carl Sagan Center for Research where she researches the intersections of astrobiology and SETI. She has a background in planetary and environmental sciences, and astrobiology.

Cabrol's research focuses on the search for habitable worlds and life beyond Earth. She has published over 470 peer-reviewed studies and proceedings of professional conferences and is the author of three books and 10 chapters of books on the subject of planetary science and exploration, astrobiology, and terrestrial extreme environments.

Cabrol also holds the women's world record for diving at altitude (scuba and free diving).

Space.com: Is the search for Mars life a template, a teaching tool, for looking for life elsewhere?

Cabrol: It depends on the scenario you are choosing. Scenario 1 is that life never appeared on Mars, period. The problem for us will be to demonstrate that. In science this is the hardest one — when do we pull the plug and just admit that there's no life on Mars and we're sure of that.

Scenario 2 is Mars has life, but unfortunately somehow we contaminated each other through planetary exchange. So it's likely to be related and not teaching us much about other types of life.

Scenario 3 is that life on Mars is found to be a separate genesis.

Mars can teach us general rules of looking for life elsewhere, and especially the relationship between life and the environment. It will teach us general rules of co-evolution for sure. Can it teach us how to search for life on Titan or on Venus? I don't think so. Those environments are so different.

Space.com: There is on-going and growing interest in Venus being a hot-bed for life.

Cabrol: If we discover life on Venus then it's extraordinary because this is pretty much the anti-Earth, a dry, super hot, super acidic environment. But the point is that we're exploring those worlds and we're learning about very different potential co-evolution. We are looking for complexity of life informing its environment and the environment informing life.

Space.com: Another thing struck me when reading your book: We're all youngsters when it comes to trying to put the puzzle pieces together about the search for life.

Cabrol: We are so young. I was born in 1963. Just a few years before that all we knew about the universe came from ground-based telescopes. My childhood [saw the] Mariner spacecraft hurled to Venus and Mars. Since then, just in 60 years, everything has literally taken off.

We are very young and the search for extraterrestrials is the same thing. We're just starting to learn what the universe is about, the diversity. What people are missing is the iteration of science. You ask a question. You build an experiment. You go and test it. Then you have the science and it's nothing like what you have predicted. Now you have to scramble and make sense of it. Develop another hypothesis. Build more experiments and test it. And this is what we're doing.

Space.com: When do you think we will find life?

Cabrol: I do get the question all the time.

I will tell you that we are close. I really do think we are close. Exoplanets are going to be a tricky one. They are so far away. We don't know where life is and we cannot bring back samples right now. Perhaps finding traces of pollution and synthetic molecules could happen, to make sure we're finding life.

As for SETI, it could come anytime and anything could land on our planet at any time too.

Space.com: And that brings me to your chapter, "Connecting Blue Dots" which includes a look at unidentified flying objects (UFOs), now rebranded in some circles as unidentified aerial phenomenon, or UAPs.

Cabrol: We're looking for aliens in the kind of world that we understand, a world of space and time with the laws that we know. And in a universe of space and time, there's a lot to be said about sending robots, that the first encounter will be the technology of a different species. If they are organics like us, then they are fragile like us.

At this point what absolutely fascinates me is the Venn diagram between astrobiology, neuroscience and quantum physics. Consciousness is a function of the brain, but perhaps the brain might just be the computer that you need to get to something that is much bigger and larger.

Experts in these areas are talking with each other and there are very interesting conversations going on. And this has incredible implications for the search for life elsewhere in the universe. There are immediate implications for how we treat life on Earth, meaning everything that is alive on this planet is conscious.

I am watching this with great interest.

Space.com: In your book, you paraphrase a comment from the late Carl Sagan that, as a scientist, "I do not want to believe. I want to know."

Cabrol: My message throughout this book is that what we have now is absolutely mind boggling. It's not only searching for life in the universe, it is also understanding how this search will actually mirror how we understand ourselves, our place on the planet, our relationship with the world and the universe around us.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

-

AboveAndBeyond I don't understand how you get "close". Either you've got an ironclad SETI detection or you don't.Reply -

Helio Reply

Her response was to a question of life. So, I took her answer to be about discovering living microbial life forms, not ETs, and in places we can now go, which isn't true for exoplanets. Her book details all the different places within in our own backyard where life might have a chance given all the prebiotics. Although she makes no claims of understanding abiogenesis -- I don't think she ever used that term in her book -- she is clearly optimistic at finding answers over the next few decades.AboveAndBeyond said:I don't understand how you get "close". Either you've got an ironclad SETI detection or you don't.

-

Torbjorn Larsson Cabrol has made good work on extremophiles.Reply

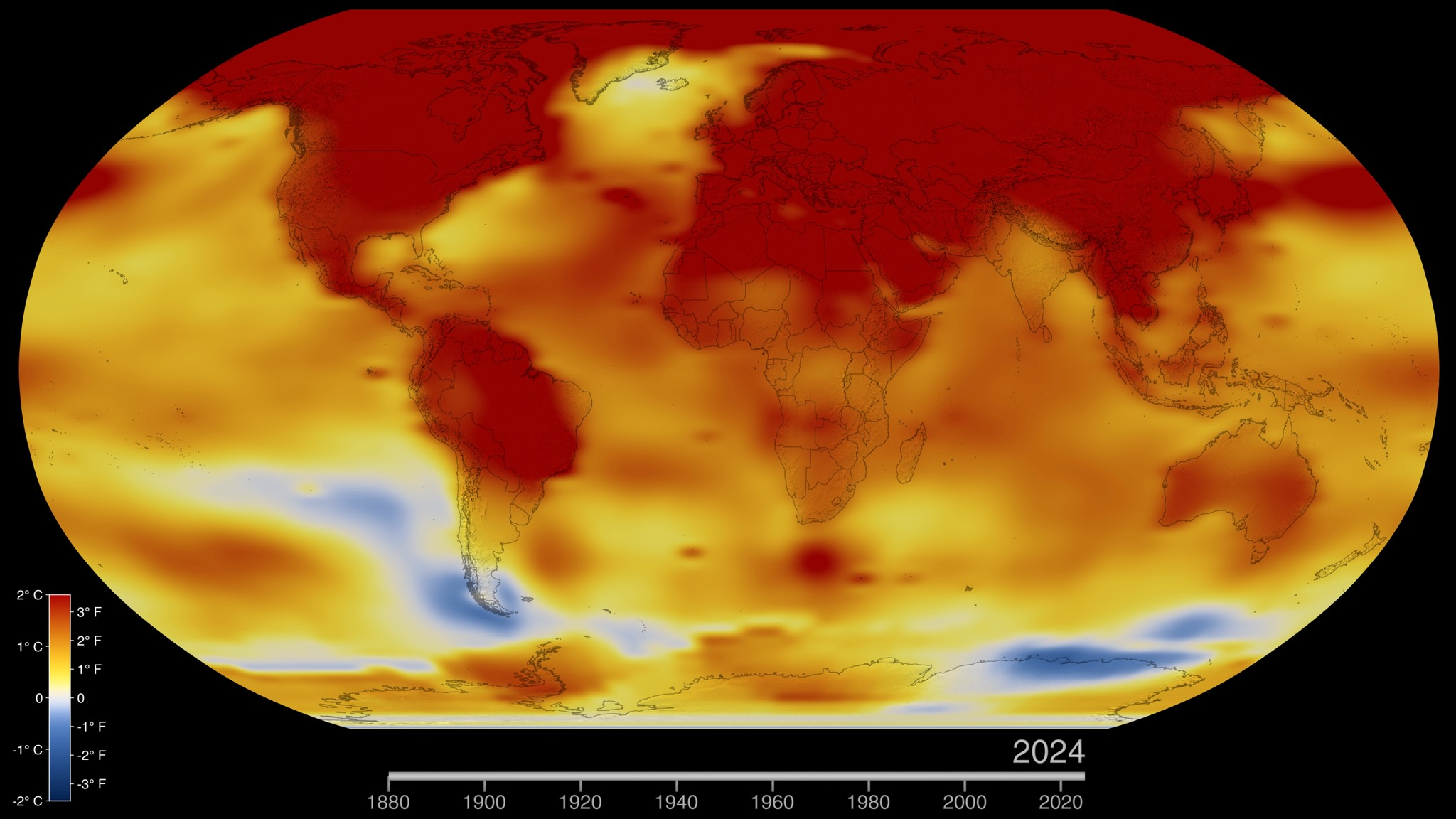

Relevance? Astrobiology is so much more than climate modelling of habitable planets!Balter said:Just need some "climate science" to find what you're looking for, works every time.

Perhaps she has some discussion in her books on the general topic - quantum physics explains spectroscopy of atmosphere planets, for instance - but not in her biology of extremophiles.orsobubu said:she lost me when blabbered about quantum physics.

She describes the ongoing work to find life with new methods.AboveAndBeyond said:I don't understand how you get "close". Either you've got an ironclad SETI detection or you don't.

Perhaps finding traces of pollution and synthetic molecules could happen, to make sure we're finding life.