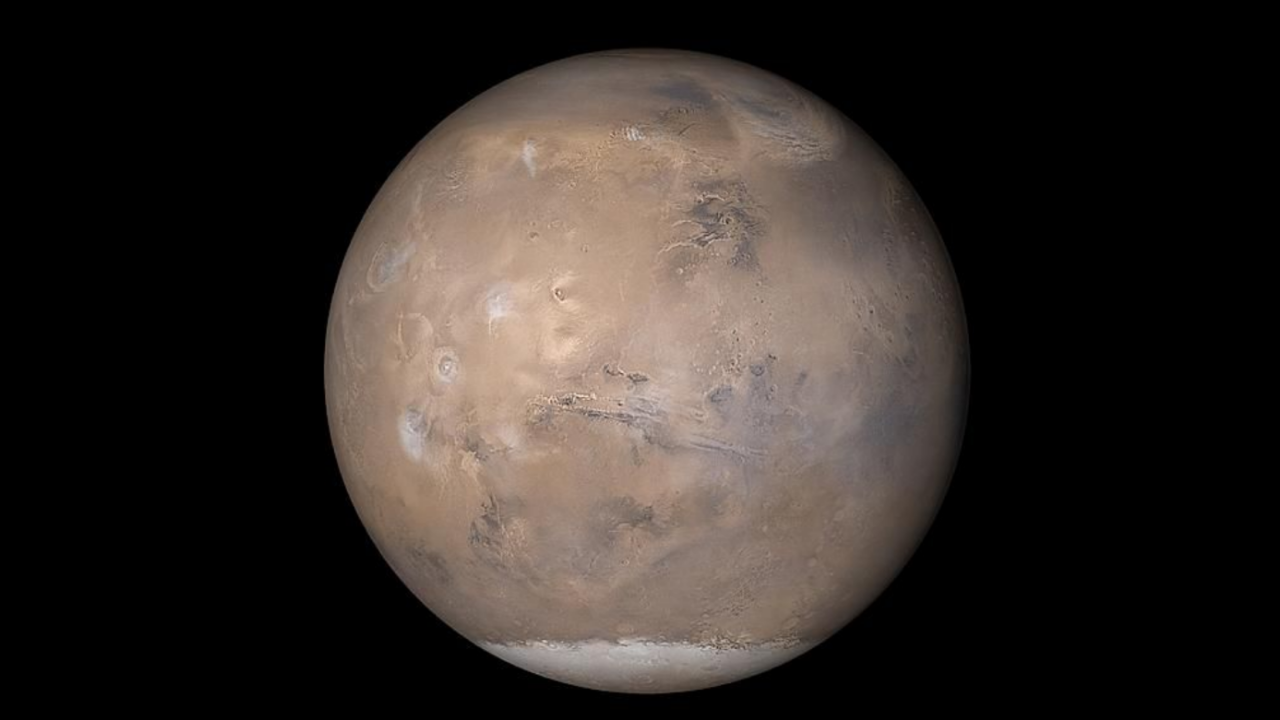

We finally know where to look for life on Mars

If — and it is a big if — there is life to be found on the Red Planet, scientists say follow the methane.

Ever since the discovery of methane on Mars, scientists have wondered if the Red Planet might harbor life. Now, researchers know where to look: deep under the surface of a broad Martian plain.

The Mars methane mystery has befuddled scientists for years. Rovers on the surface have observed seasonal fluctuations of methane, but orbiting satellites have not found any significant trace of the molecule. This kind of variability is an intriguing, but unproven, hint that a particular kind of life might exist on Mars.

Broadly speaking, however, Mars appears to be uninhabitable. The surface temperatures are usually well below freezing, there's barely any atmosphere, and deadly cosmic and solar rays constantly bombard the planet. So, while ancient Mars once had oceans and warmer climates, we're unlikely to find any living creatures on or near the Martian surface.

Related: Alien life could lurk on Mars beneath protective ice, study suggests

But we can look to Earth to find potential habitats for Martian life. On our planet, life has expanded and diversified to fill every available niche, from the upper reaches of the atmosphere to miles below the surface. Life has also found many clever ways to extract energy from the environment. Although the most common method is photosynthesis — and the resulting food web from that base — the domain Archaea consists of single-celled creatures that find energy wherever they can get it.

This includes the methanogens, creatures that "eat" hydrogen and excrete methane as a waste product. These are prime candidates for potential surviving Martian life, given the evidence for the regular appearance and disappearance of methane on the Red Planet.

In a recent paper submitted to the journal Astrobiology, scientists scoured Earth for potential analogues to Martian environments, searching for methanogens thriving in conditions similar to those on Mars.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers narrowed the list of potential habitat analogues to three categories. The first was microscopic fractures deep in Earth's crust, where the bedrock hosts tiny amounts of fluids — conditions that also might appear deep in the Martian crust. The second was freshwater lakes buried under glaciers or polar ice caps, which might exist under Mars' southern ice cap. And the last was extremely saline, oxygen-deprived deep-sea basins, which replicated the possible seasonal appearance of water on crater slopes on the Red Planet.

Scientists have already found methanogens in all of these environments on Earth, but that's not precise enough. In the new paper, the researchers mapped out the temperature ranges, salinity levels and pH values across sites scattered around the planet. Then, they narrowed down the species that thrived in conditions that resembled Martian conditions. Lastly, they surveyed the sites for the availability of molecular hydrogen, which is the primary food product of methanogens on Earth and potential life on Mars.

In particular, the researchers noted that the families Methanosarcinaceae and Methanomicrobiaceae were the most flexible, with member species living in a number of Mars-like conditions.

Next, the researchers examined available data about Mars itself. While information is scant, especially about subsurface conditions, there's enough data to put together a rough map of where liquid water might exist. Liquid water is essential for supporting all life, even the hardy methanogens. Given the circumstantial evidence for subglacial lakes and moist crater slopes, the researchers think the best chance for life is deep under the surface.

Specifically, Acidalia Planitia, a broad plain in the Martian northern hemisphere, has the best possible conditions. But the temperatures are only warm enough to support liquid water at a depth of 2.7 to 5.5 miles (4.3 to 8.8 kilometers). The researchers think the temperatures, salinity, pH and availability of hydrogen there have the best chances of matching conditions where methanogens thrive on Earth. So it's time to start digging.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.