Space mining company AstroForge identifies asteroid target for Odin launch next month

"Odin's role is to gather critical imagery of the target asteroid, preparing the way for our next mission, Vestri, which will aim to land on the asteroid and begin extraction."

A U.S. asteroid-mining company has announced the target space rock for its upcoming test mission.

California-based AstroForge has identified asteroid 2022 OB5 as the destination for its Mission 2 spacecraft, named Odin, which is set to launch next month, SpaceNews reports. The Odin spacecraft will be flying as a secondary payload aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket, which will send Intuitive Machines' IM-2 lander toward the moon.

Odin will separate shortly after the Falcon 9 upper stage fires its engines to head for the moon. The launch window for the mission opens no earlier than Feb. 26.

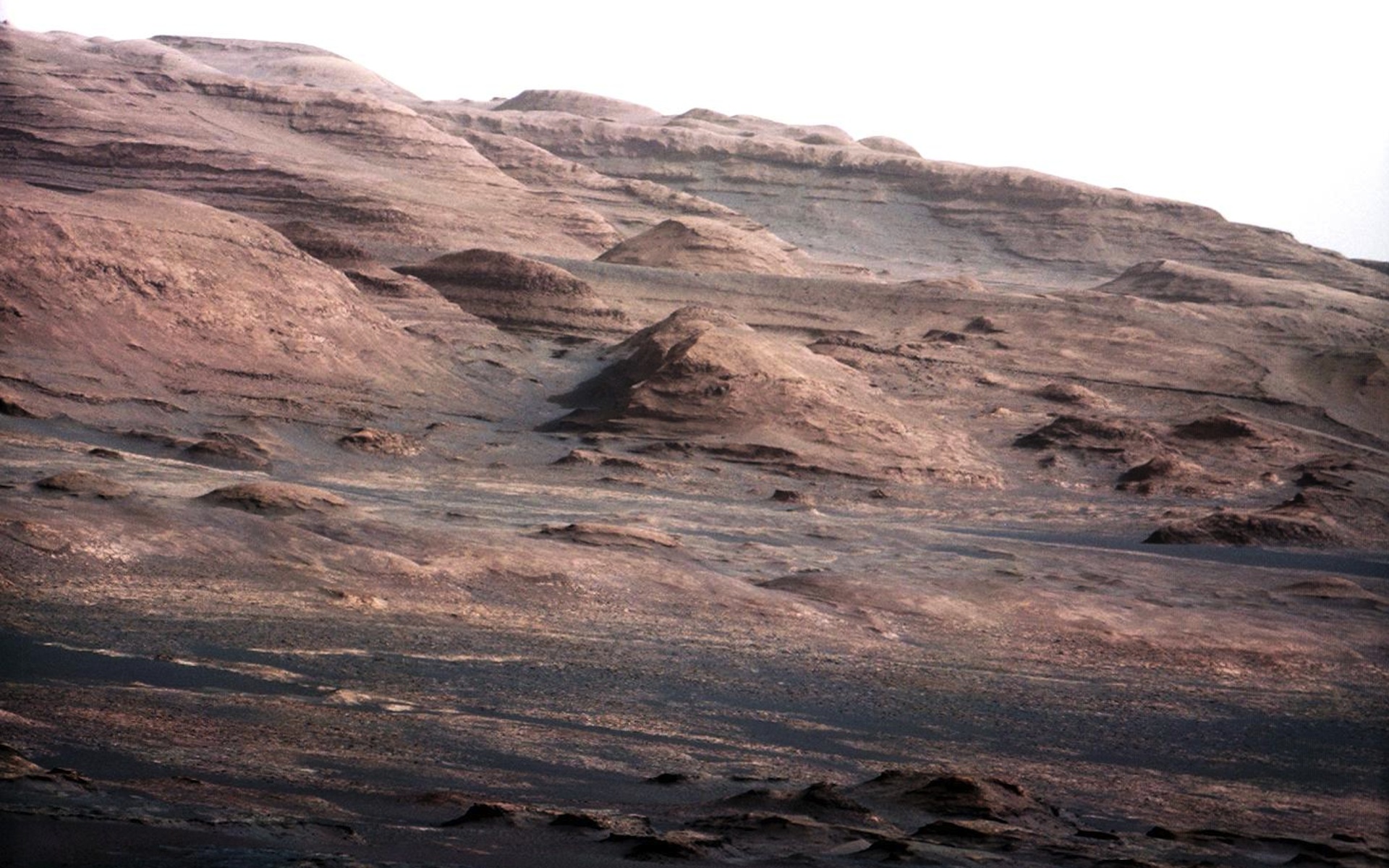

2022 OB5 is a near-Earth asteroid that is up to 328 feet (100 meters) in diameter and could be metallic. It will take Odin around 300 days to reach the small celestial body, when the small spacecraft will make a flyby to gather information about the asteroid and its suitability for mining. This is preparation for more daring missions in the future.

"Odin's role is to gather critical imagery of the target asteroid, preparing the way for our next mission, Vestri, which will aim to land on the asteroid and begin extraction," according to AstroForge.

Vestri will also be on a rideshare mission with Intuitive Machines' IM-3 lunar lander, potentially later in 2025.

Related: Space mining startup AstroForge aims to launch historic asteroid-landing mission in 2025

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

AstroForge was founded in January 2022 with plans to extract resources from asteroids and provide a sustainable solution for mining precious metals. Its first mission, Brokkr-1, reached orbit in April 2023, but the company was unable to activate the cubesat's prototype refinery technology.

SpaceNews states that AstroForge has signed a contract with Stoke Space for several launches on the in-development Nova rocket for future, ambitious mining missions.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.

-

Unclear Engineer It would be nice to get a sample of a real "metallic" asteroid, especially if it is really a fragment of the core of a demolished differentiated planetary body.Reply

But, how do they plan to get "representative" sample of the central part of this asteroid? Even if it is mostly a solid chunk of metal, its surface could still be covered with soft space dust and pebbles after billions of years of gravitational collection. -

Ken Fabian As is too common and a bit frustrating there isn't much information about the methods they intend using and certainly not a glimpse of their business plan.Reply

Sounds like the intention is to use a vaporising and separating method of PGM extraction, which I wasn't aware of as a commercial process - or as something applied to nickel-iron for this purpose. Electric arc rather than laser (lasers being very energy inefficient as a heating method) is my guess. I had been expecting Mond process - "dissolving" in carbon monoxide gas and vapor deposition, used commercially for extracting nickel, that has been proposed as a refining method for asteroid Ni-Fe, however I wonder if it actually works the way I had thought (separation of nickel and iron leaving a residue of the rest, rich in cobalt and PGM's). Some lab somewhere has likely tried it with metal meteorites but I haven't found examples. But how the mining and refining is done is still only a part of the whole exercise.

Much as they appear to have the most nickel-iron, therefore most PGM's, asteroids don't have to be M-class to have a lot of nickel-iron. Ni-Fe is very abundant, although there are variations in PGM concentrations - different Ni-Fe alloys, with higher PGMs are linked with higher nickel content. The extent to which they are found separately isn't clear.

I'm inclined to favour C-class carbonaceous asteroids that are likely to have an abundant sufficiency of Ni-Fe as grains and nodules within a softer carbonaceous matrix - for the ability to make the other things asteroid mining needs, things like rocket fuel, that I would expect to be the single largest ongoing "consumable" required.

Transport costs are what makes doing things in space so expensive; typically many times more rocket fuel than payload. I do think the efficiency and cost of the rocketry is crucial to the economics and the ability to produce fuel on-site seems crucial to cutting costs. M-class asteroids seem less likely to have the means to make rocket fuel or chemical feedstocks for more complex refinining methods and/or making the machinery and equipment on-site. -

Unclear Engineer Making actual mining a commercially viable enterprise seems pretty remote, at this time. But getting a representative sample of something that was once the core of a differentiated planetary body might provide some very interesting scientific data.Reply

For now. geologists assume that Earth's core is mostly iron, with other heavy elements like uranium mixed in. Ratios are estimated from surface samples, seismic wave analyses, ultra high pressure lab experiments, and modelling. It would be nice to get a sample, but we cannot do that on Earth - too far down, and too hot. With too much not really understood about the different layers and blobs seen in seismic data. -

Ken Fabian The mission is a fly-by reconnaissance. The previous failed one, required rendezvous, but didn't appear to have any return capability. I am deeply doubtful this will achieve commercial viability, any more than the other, failed asteroid mining companies - but without a better overview of what they intend it is hard to find much optimism that the big issues (like transport) are being addressed.Reply

At least with NASA missions the results of their surveying go into the public domain; whatever this mission learns will be private property, and when the company fails what they learn is likely to be lost.