UK startup readies new satellite that will make semiconductors in space

Semiconductors made in space may be better than those made on Earth.

A U.K. startup is preparing to send a satellite to space that will manufacture new semiconductor materials that could be used in electronic devices on Earth.

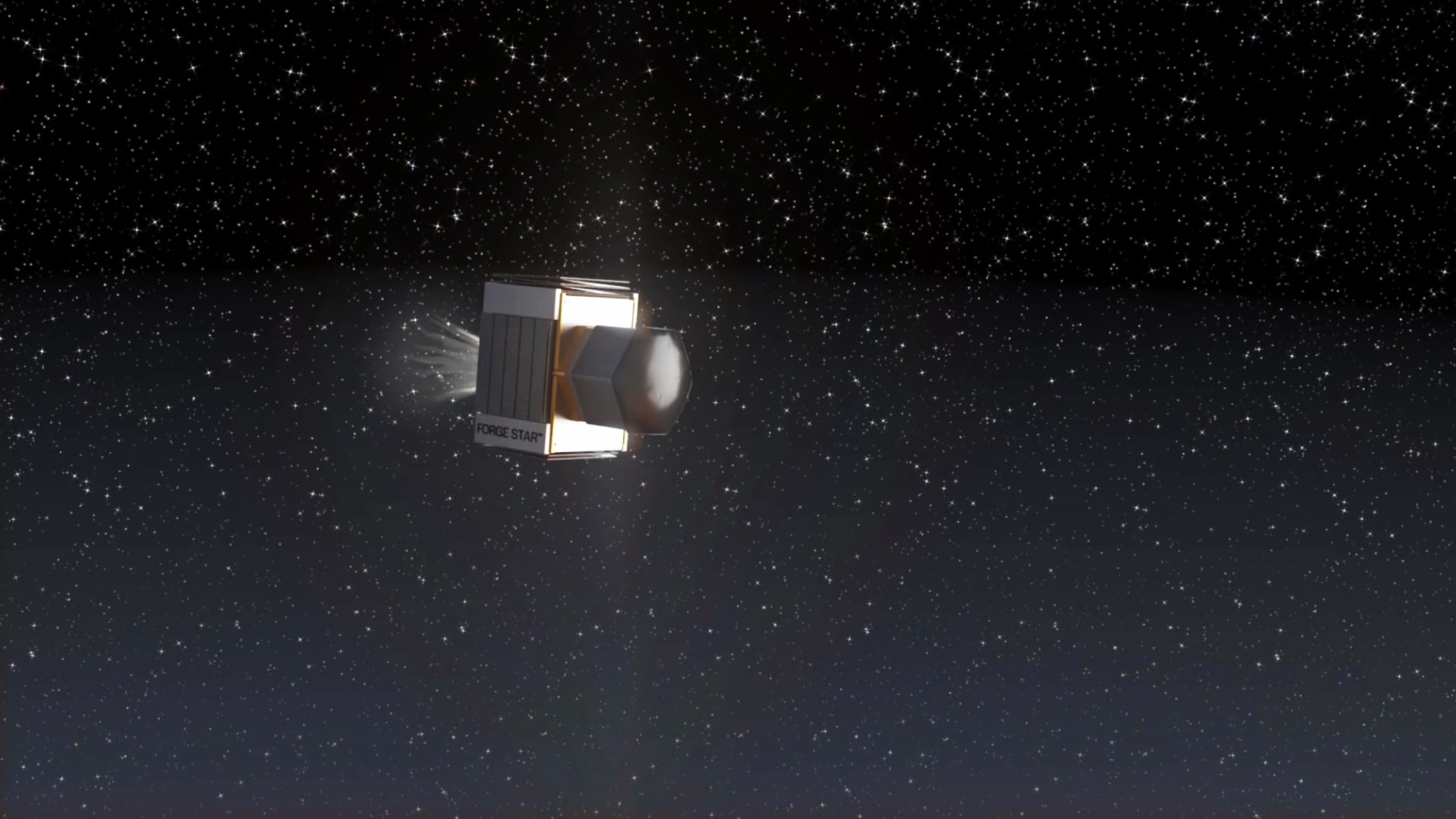

The company, Space Forge, lost their first experimental satellite in the failed launch of Virgin Orbit's LauncherOne rocket from Cornwall, the U.K., in January. Their new satellite, called ForgeStar-1, is about to ship to the U.S. for a launch at the end of this year or in early 2024, Josh Western, Space Forge CEO and founder, told Space.com.

Space Forge has recently signed a collaboration agreement with American aerospace giant Northrop Grumman to provide space-made semiconductor substrates that Northrop can then further develop in their foundries.

Semiconducting materials are essential for all sorts of electronic technologies, but their manufacturing on Earth is costly and energy intensive. The vacuum and microgravity conditions of space, however, could allow completely new semiconductor materials to be developed much more efficiently, said Western.

Related: US Space Force wants to test how to build satellites in orbit with $1.6 million Arkisys deal

"Producing compound semiconductors is a very intense and very slow process, they are literally grown by atoms," said Western. "And so gravity has a profound effect, basically shifting the bonds between those atoms. In space you're able to overcome that barrier, because there's an absence of gravity."

Space, Western added, also provides a perfect vacuum, which is necessary to protect the sensitive material from contamination. In factories here on Earth, this vacuum has to be created by industrial machines. The combination of the microgravity and vacuum of space can enable researchers to create semiconductors that are "10 to 100 times more efficient semiconductors than you have on Earth," Western added.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The microwave-sized ForgeStar-1 satellite contains a miniature, automated chemistry lab that will allow the team to remotely mix various chemical compounds and develop new semiconducting alloys once the satellite is in orbit. But rather than sending the materials back to the planet, ForgeStar-1 will beam the results of these experiments to scientists digitally as this satellite is not designed to return to Earth.

But the company's subsequent mission, Western said, will be built to survive the fiery return through the atmosphere and bring its products back to Earth. The company will not concentrate solely on semiconductor manufacturing but will use their satellites to host other industrial processes as well. Western said the first returnable satellite might be launched in two or three years.

The global semiconductor industry is currently worth more than $500 billion and is expected to double in size by 2030.

"This growth is expected to require investment in high-end advanced wafer manufacturing materials, equipment, and services," Space Forge said in an emailed statement. "In-space manufacturing offers unique advantages, such as microgravity and vacuum conditions, that can lead to the creation of semiconductors with superior performance and reduced defects compared to those manufactured on Earth."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.