Astronauts in space will soon resurrect an AI robot friend called CIMON

This time, CIMON will be a smarter space robot.

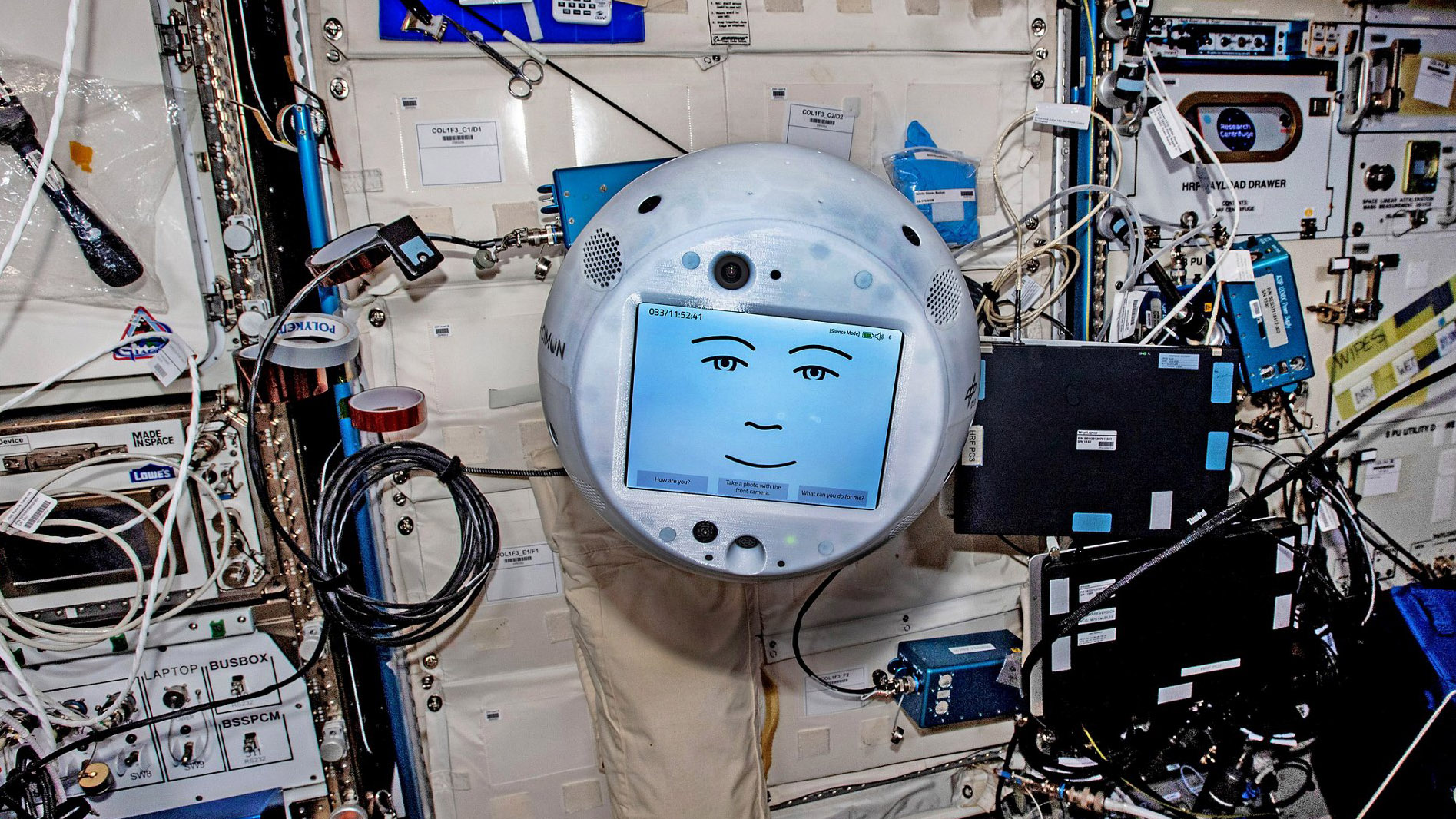

An AI-powered robot with a digital face is ready for a new mission on the International Space Station.

The robot, called CIMON-2 (it's short for Crew Interactive Mobile Companion) worked alongside two European astronauts on past missions to the station in recent years and just got a software upgrade that will enable it to perform more complex tasks with a new human crewmate later this year.

The cute floating sphere with a cartoon-like face has been stored at the space station since the departure of the European Space Agency's (ESA) astronaut Luca Parmitano in February 2020. The robot will wake up again during the upcoming mission of German astronaut Matthias Maurer, who will arrive at the orbital outpost with the SpaceX Crew-3 Dragon mission in October.

In the year and a half since the end of the last mission, engineers have worked on improving CIMON's connection to Earth so that it could provide a more seamless service to the astronauts, CIMON project manager Till Eisenberg at Airbus, which developed the intelligent robot together with the German Aerospace Centre DLR and the LMU University in Munich, told Space.com.

Related: A floating 'brain' will assist astronauts aboard the space station

"The sphere is just the front end," Eisenberg said. "All the voice recognition and artificial intelligence happens on Earth at an IBM data centre in Frankfurt, Germany. The signal from CIMON has to travel through satellites and ground stations to the data centre and back. We focused on improving the robustness of this connection to prevent disruptions."

A robot friend in space

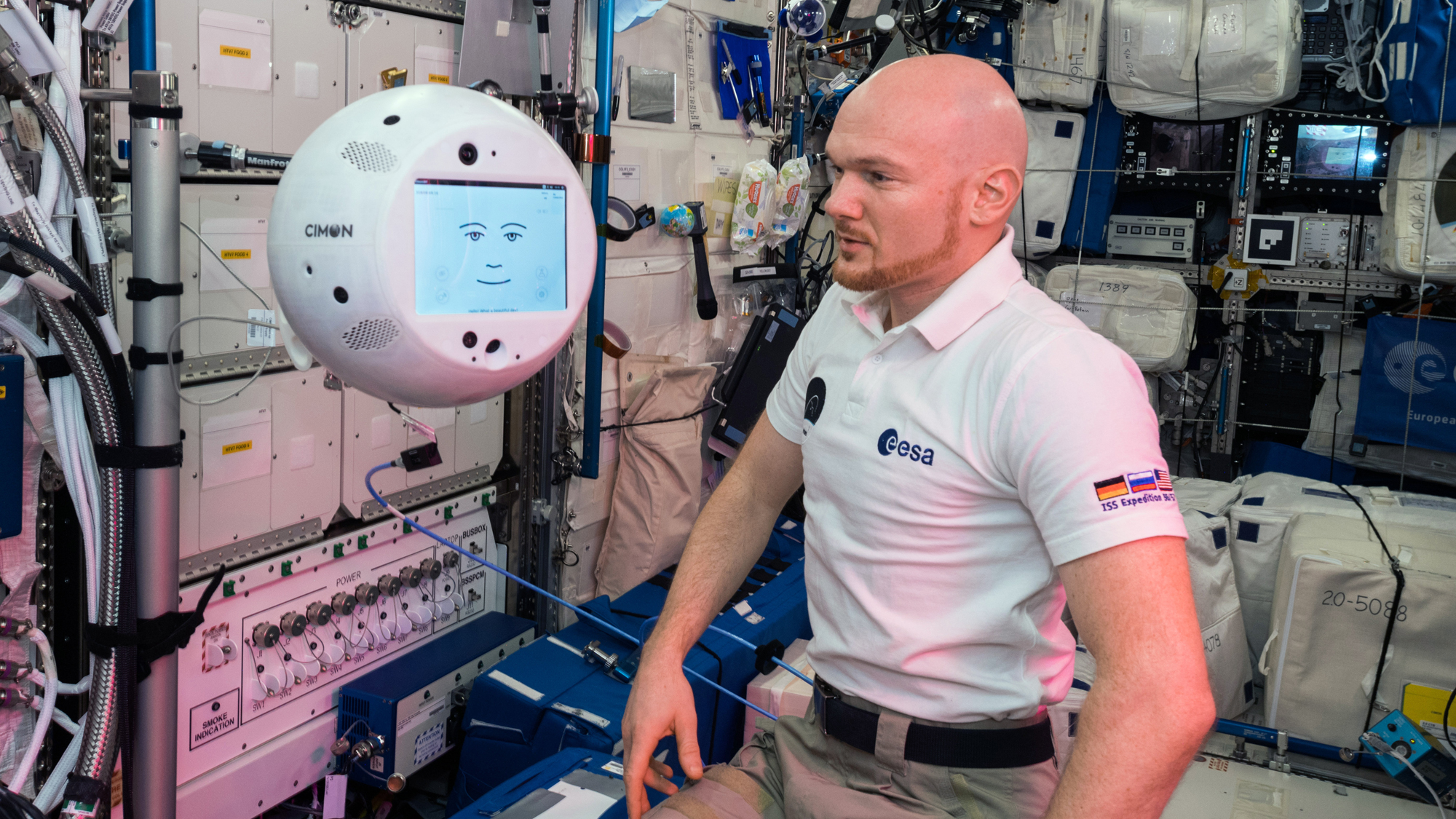

CIMON relies on IBM's Watson speech recognition and synthesis software to converse with astronauts and respond to their commands. The first generation robot flew to the space station with Alexander Gerst in 2018. That robot later returned to Earth and is now touring German museums. The current robot, CIMON-2, is a second generation. Unlike its predecessor, it is more attuned to the astronauts' emotional states (thanks to the Watson Tone Analyzer). It also has a shorter reaction time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"During the first steps in the development process, we had a delay of about ten seconds, which was not very convenient," Eisenberg said. "Through improving the software architecture we managed to get down to two seconds, just in time for the first mission. With further software upgrades, we have now tried to eliminate delays that might occur when the connection breaks."

Airbus and DLR have signed a contract with ESA for CIMON-2 to work with four humans on the orbital outpost in the upcoming years. During those four consecutive missions, engineers will first test CIMON's new software and then move on to allowing the sphere to participate in more complex experiments.

During these new missions CIMON will, for the first time, guide and document complete scientific procedures, Airbus said in a statement.

"Most of the activities that astronauts perform are covered by step by step procedures," Eisenberg said. "Normally, they have to use clip boards to follow these steps. But CIMON can free their hands by floating close by, listening to the commands and reading out the procedures, showing videos, pictures and clarifications on its screen."

The robot can also look up additional information and document the experiments by taking videos and pictures. The scientists will gather feedback from the astronauts to see how helpful the sphere really was and identify improvements for CIMON's future incarnations.

Building a smarter space robot

For now, CIMON has only been trained to navigate in the European Columbus module of the space station, Eisenberg said. The 11-pound (5kg) sphere floats around using its small air jets. A set of ultrasonic sensors together with a stereo camera help the robot navigate in space and avoid walls and equipment. CIMON is also fitted with a high-resolution camera that enables it to recognise faces of individual astronauts. Two smaller cameras on the sphere's sides are used to take pictures and videos. An overall nine microphones help CIMON to identify the source of sounds and detect and record speech.

In the future, the team hopes to make CIMON independent on the ground-based data center. Astronauts on future missions to the moon and Mars will surely appreciate a robotic assistant. However, for such missions it would be impossible to wait for the speech processing to be done on Earth.

"There is already enough computational power aboard the space station that would be able to support CIMON," Eisenberg said. "It's only a question of sharing these computational resources. But we want to start working in parallel on CIMON-3, which would be able to use services directly on board without the need of a connection to the ground."

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.