Here are 6 times that spacecraft smacked into other worlds — for science!

It's a whole new spin on going out with a bang.

The humans behind spacecraft try to make their robotic emissaries work for as long as possible. But sometimes, spacecraft must be destroyed anyway and sometimes, it takes destroying a spacecraft to get the maximum science out of a mission.

And scientists are never quick to reject any observations on principle. So while plenty of spacecraft have drifted away into the metaphorical sunset, some have made dramatic exits. Those parting flourishes have given scientists unprecedented views into the solar system, with plenty more to come.

Scott Bolton has worked with two spacecraft that destroyed themselves in the name of ensuring that terrestrial microbes could never gain a foothold in the outer solar system. Both carefully choreographed exits produced their own science.

"I don't want to make it sound like scientists wanted to do this," Bolton, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute, told Space.com. "This is basically, you're dealt lemons and you're trying to figure out how you can make lemonade."

Related: NASA's DART asteroid-impact mission explained in pictures

A few almost-rans for space impacts

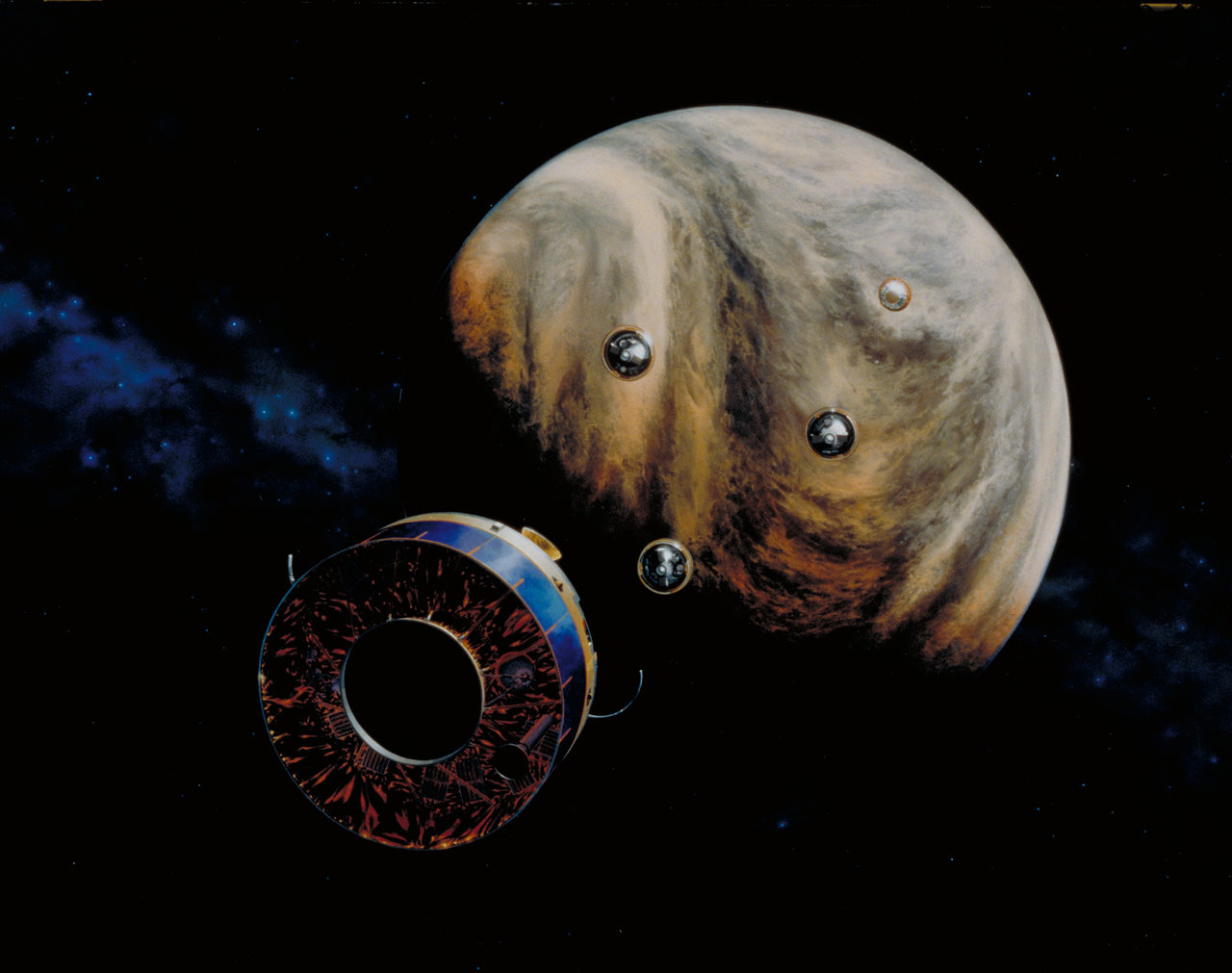

Missions braving the harshest conditions are inevitably bound to go out in a blaze of glory. Take, for example, every single spacecraft that has entered Venus' atmosphere; the longest survivor of that planet's surface lasted just two hours.

"A probe by definition is sort of a suicide mission, but it's designed that way," Bolton said. He worked on the Galileo mission to Jupiter, for example, which included a probe that descended through the planet's atmosphere, sending back 57 minutes of data covering 97 miles (156 kilometers) into the clouds, according to NASA.

But that's different than tossing in a full-fledged spacecraft, he emphasized. "I would never advocate, 'Go do this for the measurement.'"

For convenience, the rest of this roundup includes only primary spacecraft rea

Galileo at Jupiter in 2003

Nevertheless, the Galileo spacecraft itself ended up following that descent probe. Galileo's end was determined, ironically, by its own discovery of plumes of water bursting through the icy shell of Jupiter's moon Europa. The find turned Europa into a hot topic for astrobiologists and meant that no one wanted a dying spacecraft potentially covered in Earth germs to stumble into the icy world.

Galileo had to be disposed of safely instead, before it finally ran out of fuel. By the time the spacecraft plunged in, it had completed nearly eight years of a planned two-year mission, and scientists knew the end was near. "We took it in stride because, destroyed or not, the mission was going to be shut off," Rosaly Lopes, a planetary scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in California who worked on Galileo early in the mission, told Space.com.

But destroying a spacecraft with the atmosphere of the largest planet in our solar system is easier said than done.

"You basically spiral in," Bolton said. "You can't just make a left turn at a stoplight and head toward Jupiter; you're in orbit around it and dictated by Kepler's laws, and you slowly move your way in, so there was this great opportunity to make a lot of measurements."

Scientists got to work thinking about what they could do during the spacecraft's long goodbye. "There were a lot of limits to what Galileo could do," Bolton said. "Its instrumentation was really designed to look at things from afar, so it didn't have some of the instrumentation that, if you were going into Jupiter's atmosphere, you would have liked." And the spacecraft's antenna hadn't deployed properly, reducing the amount of data scientists could get back throughout the mission.

But even with those challenges, the 2003 dive gave scientists brand-new data about the massive planet's magnetic field and radiation belts and the charged particles surrounding Jupiter, Bolton said.

Deep Impact hits Comet Tempel 1, 2005

It's right there in the mission's name: NASA's Deep Impact spacecraft hurled an 820-pound (372 kilograms) impactor into Comet P/Tempel 1, allowing scientists to study the inside of one of these "dirty snowballs" of the solar system.

The spacecraft launched in January 2005 and had arrived at Comet P/Tempel 1 by mid-June, just in time to spot two natural outbursts from the comet. But the real fireworks came on July 4, 2005, when the comet and impactor collided.

According to NASA, the resulting crater on Tempel 1 is about 490 feet (150 meters) across.

The main spacecraft flew past just minutes later to photograph the dust-filled crater, the icy debris from the explosion and the comet's main body; Deep Impact then went on to fly past a second comet, 103P/Hartley 2, before falling silent in 2013.

LCROSS hits the moon, 2009

The Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) mission launched with NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and looked on as the launch's spent rocket stage crashed into the moon in October 2009. The mission's unusual format was inspired by a desire to observe a tricky neighborhood of the moon, and by the Apollo program's history of using rocket boosters to create seismic waves for instruments to detect.

The LCROSS team wanted to use a similar approach to bring a sample of interior rock from the moon's dark south pole into light. LCROSS's booster was smaller, but it entered on a path designed to maximize the collision, and it was accompanied by an entire separate spacecraft's worth of instruments fine-tuned to study the events in incredible detail for four minutes after impact, before that spacecraft too crashed into the moon.

"I remember driving in for that final shift and looking up at the moon as I drove in and wondering to myself, as you might — is this going to work?" Anthony Colaprete, a planetary scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California who was principal investigator for the LCROSS mission, told Space.com.

It did indeed work. LCROSS was designed to get around two problems with studying the subsurface of the moon's south pole. First, the area hasn't seen sunlight in billions of years, so orbiters can't simply catch reflected light from the region. Second, landing softly on the moon to see below the surface is difficult. The impact gracefully addressed both challenges with a relatively cheap mission.

"It brought up a lot of material and in a way, sampled a broad region that a drill could never sample without mobility," Colaprete said of the LCROSS approach. "That allowed us to basically bring a large sample into view where we could observe it."

A key moment during the day of impact came when the science spacecraft spotted the crater that the booster had left behind.

"That was huge," Colaprete said. (The crater itself, coincidentally, was also huge — nearly 100 feet, or 30 m, across and 16 feet, or 5 m, deep.) "That really confirmed the size of the crater, and also it saw some of the ejecta coming down above the crater as well, so it was incredibly valuable."

That glance was basically it for the crater proper, since the team had just four minutes to gather data about the impact and NASA's current lunar orbiter can't see the region. "That's the only image so far of the post-impact crater," Colaprete said, although the team did also snag radar data showing the roughness of the site.

Colaprete still holds out hope for a better look at the mess LCROSS left behind, noting that an instrument that South Korea plans to put in orbit around the moon should be able to see the site despite the lack of sunlight. If it can, the instrument could see not only the main impact crater, but also the one left by the science spacecraft, which scientists expect is about one third the size. "It itself then becomes an experiment," Colaprete said.

Despite the crater left behind, Colaprete does emphasize that the LCROSS mission didn't necessarily target the moon so much as follow a very specific orbit. "We did not impact the moon; the moon got in our way," he said. "We were orbiting the Earth, and the moon got in our way."

Messenger hits Mercury, 2015

NASA's Messenger mission launched in 2004 and arrived in orbit around Mercury in 2011, then spent four years orbiting the tiniest planet in the solar system. Messenger mapped the planet, studied its geology and measured its magnetic field. But in 2015, it came to its own abrupt end, likely skidding to a halt at a cliff face, Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland who took part in the mission, told Space.com.

"That was always destined to be Messenger's fate," Chabot said. "Once it went into orbit, it was never going to leave orbit, and it wasn't going to be able to orbit forever, so it was sort of on a one-way track to the impact into the surface at some point."

But Messenger's impact wasn't like many of the controlled impacts that have sought to approach a surface at as close to a 90-degree angle as possible. "It's kind of barely skimming the surface until it doesn't," Chabot said of Messenger's descent. "It'll have a very flat kind of coming in as compared to sort of head on, so that also should make an interesting shaped crater."

While the Messenger team knows when the spacecraft hit, no one has caught a glimpse of the site since then. However, that might change, thanks to a Mercury mission called BepiColombo run by the European and Japanese space agencies. Chabot said that given what scientists expect about Messenger's crater, they can't be sure yet whether BepiColombo will be able to image the crater. But if it can, the results may teach scientists more about the closest planet to the sun.

"We haven't done any science on that, it hasn't produced any useful data yet, but it has the potential to, and I think that's also kind of exciting," Chabot said. "That could be an added legacy of the Messenger mission, I suppose."

Cassini hits Saturn, 2017

NASA's next gas giant mission launched before Galileo's end, but the team behind the Cassini mission to Saturn knew their own spacecraft might be facing a similar fate at the end of its work. And sure enough, scientists knew they didn't want to risk an uncontrolled crash by the non-sterilized spacecraft on Titan or Enceladus, two potentially habitable moons of the ringed planet.

"We looked at all sorts of things: We could've put Cassini in this great big orbit well outside of Titan's orbit," Linda Spilker, a planetary scientist at JPL and the last project scientist for the Cassini mission, told Space.com. "We could have sent it off to another planet, back to Jupiter, maybe out to Uranus."

But when a team realized that the right Titan flyby would send the spacecraft first into the gap between planet and rings, then inevitably down into the planet itself, the temptation was clear.

Related: In photos: Cassini mission ends with epic dive into Saturn

"The scientists had a range of options of what they could do, but this one, this chance to go so close to Saturn and to address new science questions and satisfy planetary protection, was like win, win, win for the Cassini mission and so that's what we chose to do," Spilker said.

So in 2017, during the last six months of its explorations, Cassini got a whole new view of Saturn as scientists ran through a wishlist of observations that the spacecraft couldn't make earlier in the mission. "There was a whole host of new science that we could do, and that was really a very nice bonus," Spilker said. "We probably wouldn't've thought to try that necessarily, except for the fact we had to satisfy planetary protection."

The mission's finale allowed scientists to calculate the mass of Saturn's rings, to confirm a phenomenon dubbed "ring rain," to determine that Saturn's rotational and magnetic axes are inexplicably similar, and to gather some of the same types of data about charged particles as Galileo had during its own descent 14 years before.

Hayabusa2 hits asteroid Ryugu, 2019

Japan's second asteroid-sampling mission, Hayabusa2, visited a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu with a host of smaller robotic explorer companions. Also tucked aboard the spacecraft was an experiment called the Small Carry-on Impactor, or SCI, that the mission deployed in April 2019.

With this project, the mission team planned to essentially fire a bullet at the asteroid, creating an artificial crater. The mission was even able to catch a photograph of debris splashing out from the asteroid during the impact.

Ryugu itself had already surprised the mission team, as it was much rougher than scientists had predicted from a distance. And the impact, too, wasn't necessarily what asteroid scientists expected.

"That crater just seems to have been such a weak sort of material," Chabot said. "It shows you why we really need to do these experiments on real asteroids in space to understand them. Every experiment that we do is a little bit surprising."

Hayabusa2's impact also made a second type of science possible. The main spacecraft had already collected samples of rock from the asteroid's surface, but after the impact, Hayabusa2 swung in again for a final sampling maneuver inside the crater.

The additional sample meant that once the spacecraft delivered its cargo to Earth in December 2020, scientists could compare the exposed surface of the asteroid with its interior, where rock had been protected from space weathering for countless years.

Next up: DART to hit asteroid Didymos moonlet Dimorphos

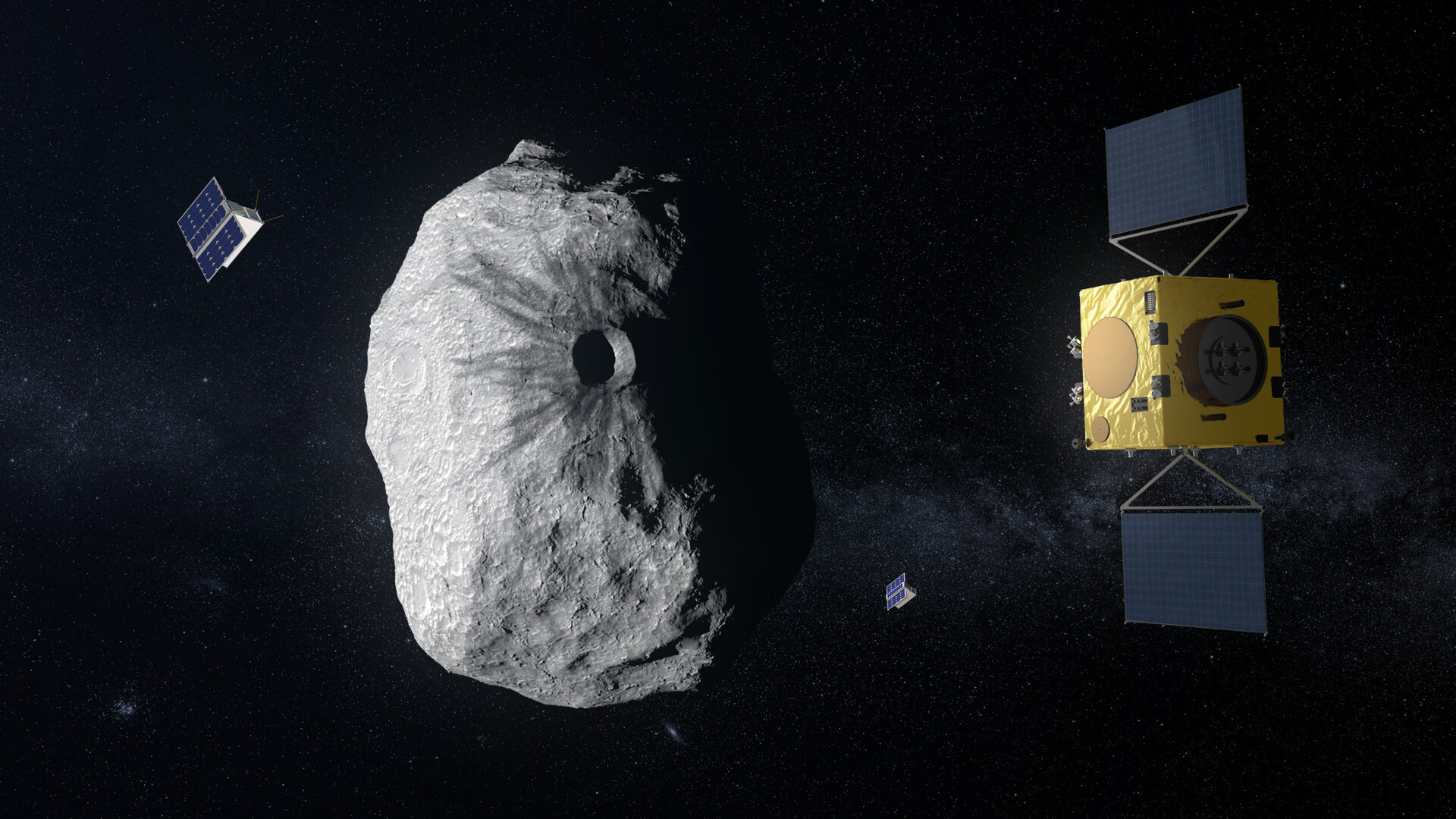

Next year, another spacecraft will join the ranks of stunning departures. NASA's Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART), which is scheduled to launch this fall, is bound for a pair of near-Earth asteroids. When it arrives in the autumn of 2022, DART will deploy a small cubesat, then crash into the smaller of the pair, a rock called Dimorphos.

The $330 million mission is NASA's first planetary defense mission and is designed to help scientists understand what would truly be necessary to redirect an asteroid that appeared to be on a collision course with Earth. But asteroids, of course, are also fascinating scientific targets. While DART doesn't carry any scientific instruments, its cubesat will film the entire impact to beam back to Earth, and a successor mission from the European Space Agency called Hera will study the crater later this decade, after the dust has cleared.

"That's one of the reasons that we're really excited about Hera as well, because you will be able to see that impact crater then, which will tell you a lot about how this material is put together," Chabot said.

Even the science observations will in part feed into the mission's planetary defense priorities, since different structures of asteroids may respond to deflection attempts differently — and, in turn, will crater in different ways.

"The models that our impact group runs predict very different craters depending on how strong that material is, depending on how the boulders are distributed on the surface," Chabot said.

To date, scientists have generally been surprised by what asteroids look like up close. Both Hayabusa2 and NASA's OSIRIS-REx asteroid-sampling mission arrived at their targets and showed scientists much more rugged worlds than expected. But scientists also wonder whether an asteroid as small as Dimorphos would follow that trend.

"Is it more of a coherent shard of material, or is it really just still this loosely held together kind of rubble pile?" Chabot said. They're questions that DART will destroy itself to help answer.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.