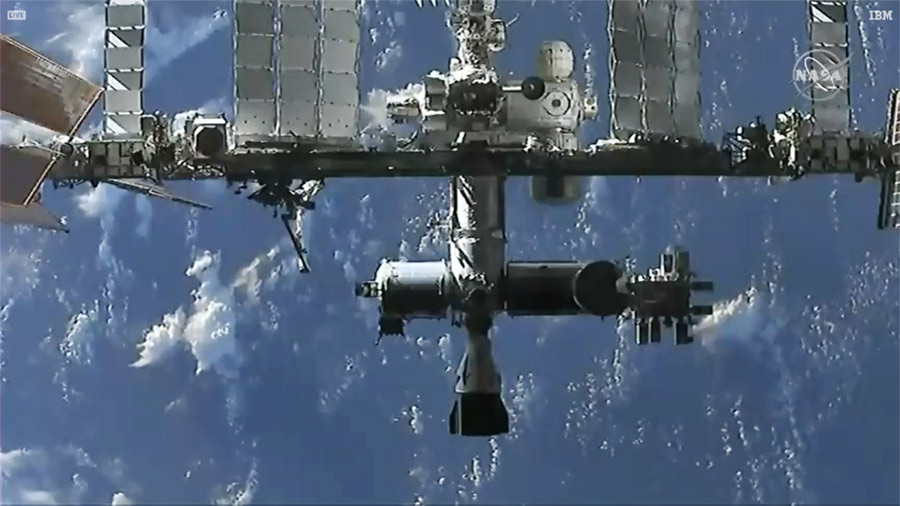

SpaceX Dragon cargo ship delivers Christmas presents (and supplies) to space station

A turkey dinner and presents arrived in time for the holidays.

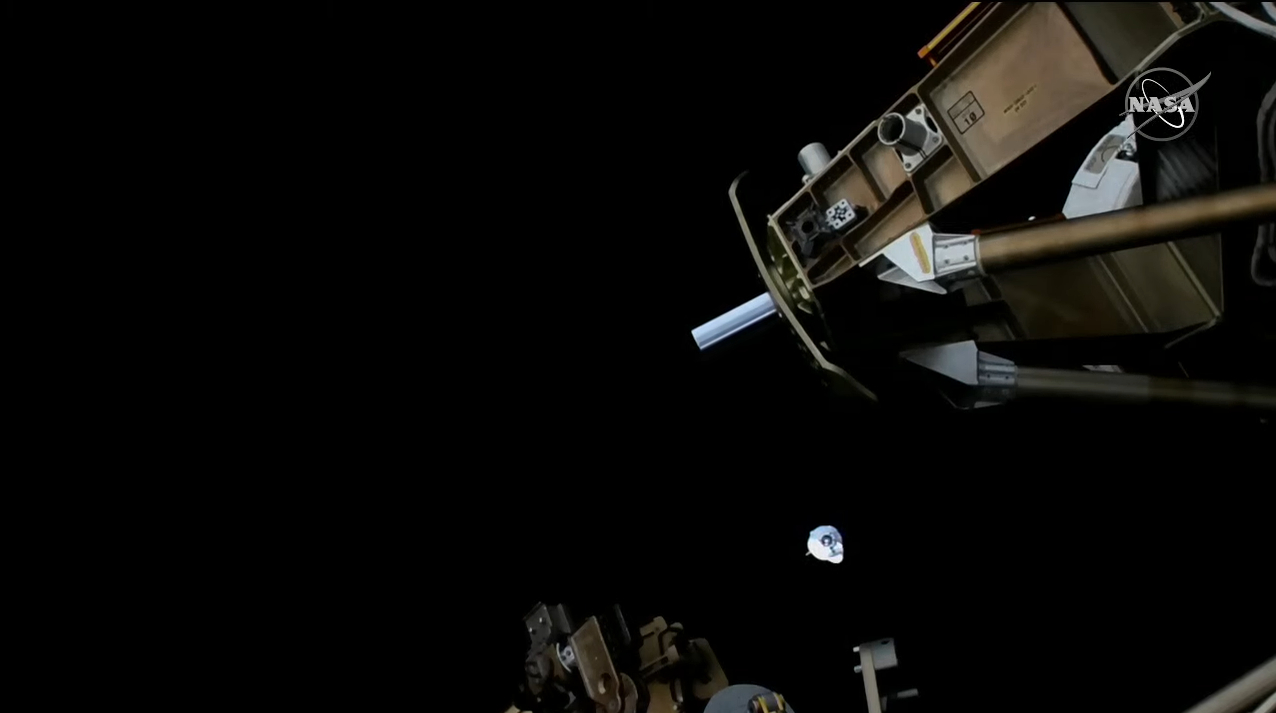

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — A SpaceX Dragon capsule arrived at the International Space Station early Wednesday (Dec. 22), carrying with it a holiday haul of science gear and Christmas treats for the astronauts living on the orbital outpost.

The autonomous Dragon resupply ship docked itself at the orbital outpost at 3:41 a.m. EST (0841 GMT), ahead of its planned 4:30 a.m. docking time. It parked itself at the space-facing port on the station's Harmony module, with NASA astronauts Raja Chari and Tom Marshburn monitoring the docking from inside the station.

The Dragon capsule blasted off on its cargo mission for NASA, called CRS-24, early Tuesday (Dec. 21) atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida. It delivered 6,500 pounds (2,949 kilograms) of research experiments and supplies for the crew. With Christmas just days away, NASA did pack a special dinner for the seven astronauts on the space station.

"I won't get in front of Santa Claus and tell you what's going to be sent up, but we are going to have some gifts for the crew," said Joel Montalbano, NASA's space station program manager, before the Dragon launched. "We're also going to fly some special foods for Christmas dinner. So you can imagine turkey, green beans, we have some fish and some seafood that's smoked. We also have everybody's favorite, fruitcake."

The research gear tucked inside will support a variety of experiments in the life sciences, pharmaceuticals, and many other fields.

Space laundry with Tide

NASA's upcoming Artemis moon missions will send crews back to the moon for the first time in decades, but it will also serve as a stepping stone to Mars. To that end, NASA is trying to figure out how it will feed, clothe, and protect its astronauts on extremely long-duration missions.

One investigation flying on CRS-24 will help them do just that. Together with Proctor and Gamble, the makers of Tide detergent, NASA is looking at how to wash clothes in space. This initial step will test how well the actual detergent holds up to the stresses of microgravity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The agency estimates that it will need approximately 500 pounds of clothing per astronaut for a three-year trip to Mars. That amount can be decreased by providing the crews with the capability of washing clothes in orbit. (Currently, astronauts wear their clothes many times before tossing them out and grabbing a new set.)

"Once you start having extended trips out in space, laundry is a must-have," Mark Sivik, senior director and research fellow at Proctor and Gamble told Space.com. "We looked at what it would take for a crew of four to do laundry and we minimized that."

"What we've developed here is fully degradable and designed to work within the space station's closed-loop system," he added.

The Tide experiment will help put NASA on a path that leads to laundry in space. For this first iteration, researchers will be looking at how the specially designed detergent performs in space. Tide is also sending up a follow-on experiment next year that will look at how effective the detergent is at fighting stains while in space.

The detergent used will be a scaled-back version of the detergent we use at home, that is designed specifically for performance apparel. Since the astronauts work out multiple times per day, and wear more performance-active clothing, this is what the detergent will target.

It will run for about six months, coming back to Earth sometime during the summer. The research will not only provide future space travelers with a means of freshening their clothes but could prove effective for people in areas that don't have immense water supplies. That's because the detergent is designed to be used with less water while also performing as you would expect.

Perfecting crystal growth

Protein crystal growth experiments are commonly sent to the space station because microgravity is an excellent platform to grow perfect, uniform crystals.

The crystals can then be used to test a variety of different drugs to treat ailments from arthritis to cancer.

Inspiration for one such treatment came from the body's own immune system. Monoclonal antibodies (MAB) attack a specific target by triggering the body’s immune response.

Given via transfusion, monoclonal antibodies can be made to lock onto specific targets inside a cell (or on its surface) and have fewer side effects compared to other treatments. However, in order to be an effective form of treatment, the MABs need to be administered in large doses intravenously. By sending this experiment into space, the pharmaceutical company Merck Research Labs is hoping it can make higher concentrations of high-quality antibodies.

It's also hoping that other companies will see the simplicity of its experiment and be inspired to do their own space-based research. Paul Reichert of Merck told Space.com that the idea for this experiment came in 2016 after he saw a video of NASA astronaut Kate Rubins using a pipette as part of another investigation.

Reichert realized that experiments didn't have to be incredibly complex to get the same results. The design of this experiment is simplistic, comprised of a few syringes affixed to a board. Reichert said that he hopes to be able to grow many small, perfectly-shaped protein crystals that the company can then use to improve its cancer treatment therapies.

STEM in space

Students from two different universities are sending experiments into space as part of NASA's Student Payload Opportunity with Citizen Science (SPOCS). The teams partnered with students in grades K-12, which acted as citizen scientists, as a means of doing real-world research.

Engineering students at the University of Idaho developed a payload to look at how microgravity affects bacteria-resistant polymers. Studies conducted on the station have revealed that bacteria are present on surfaces around the space station, and this experiment hopes to determine which coatings (polymers) have the best bacteria-resistant properties.

"The goal of our project is to help further space travel by reducing bacteria growth and disease on the International Space Station," Adriana Bryant, the team leader, told Space.com.

The team worked with a class of third graders from Moscow, Idaho to select two bacteria-resistant polymers that were sent into space. The experiment will run for roughly 30 days and is designed to be fully autonomous once it's plugged into the space station's power.

Teams will analyze the data collected when it comes back to have an idea on which of its polymers are the most resistant to bacteria in space.

Another team from Columbia University will look at antibiotic resistance in microgravity. The team is sending two different types of bacteria into space, which are known to interact here on Earth. The experiment will run for approximately 14 days and once its data is received back on Earth, the Columbia team are hoping to determine how each bacteria behaves individually when treated with certain antibiotics and how they behave together in space and how effective treatments are for it.

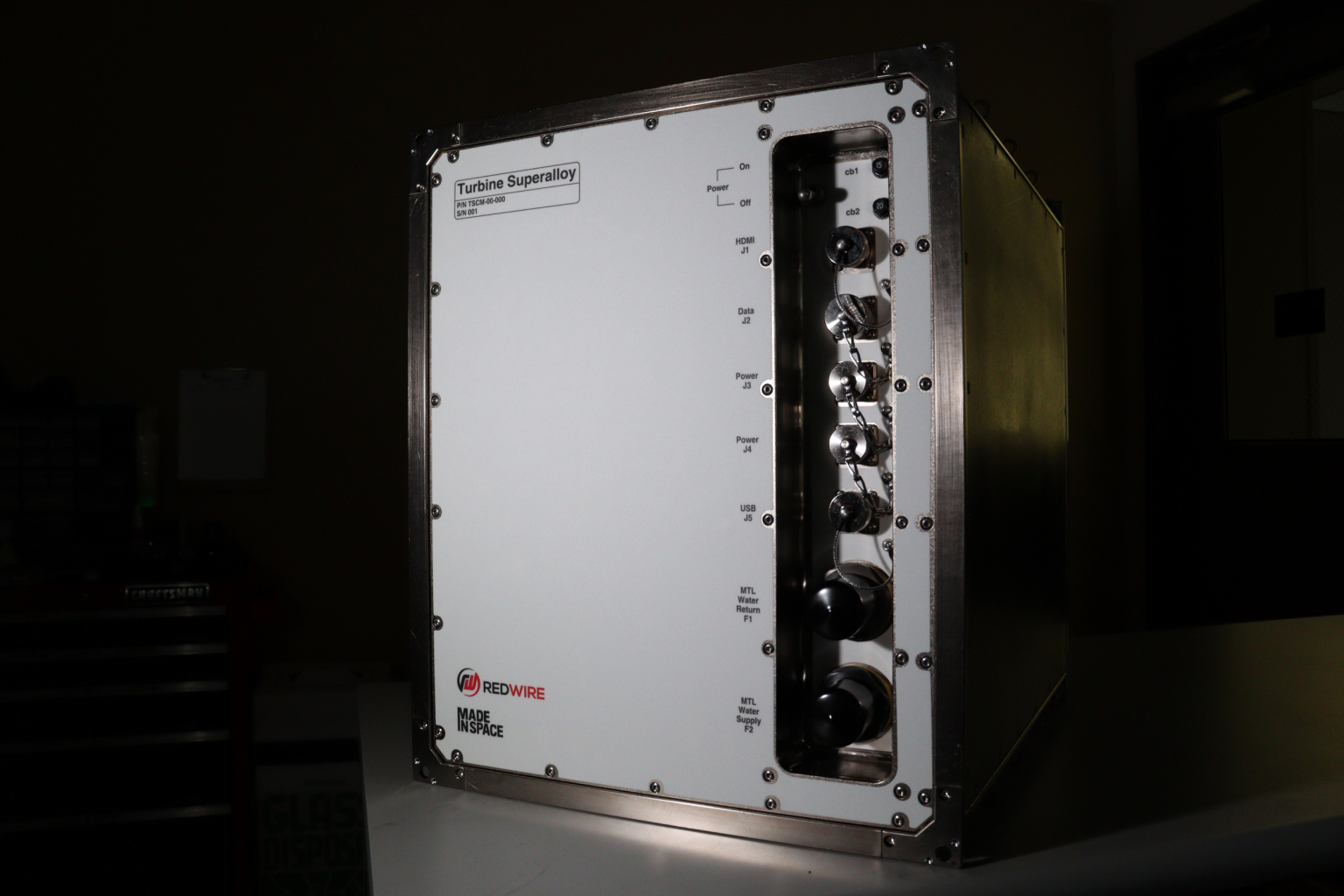

3D-printing a superalloy in space

The Turbine Superalloy Casting module (SCM) is a commercial manufacturing device that processes heat-resistant alloys in microgravity. Alloys are materials that are made of at least two different chemical elements, one of which is a metal.

The experiment is designed by Redwire Space, which has already sent numerous payloads into orbit, including the first 3D-printer in space by Made In Space, which Redwire acquired in 2020.. By trying to print alloys in space, the company is hoping to look to the future when humanity will need to build things on other worlds as well as improve products here on Earth.

The team is expecting to see more uniform structures in the space-based prints versus the ones done terrestrially, which could help produce improved materials here on Earth, like turbine engines. These types of engines are used not only in the aerospace industry but also as a means of generating power.

The Dragon capsule is on its second trip to the International Space Station (it first flew in June of this year) and will remain docked to the orbital outpost for roughly 30 days. It will return to Earth in January.

Follow Amy Thompson on Twitter @astrogingersnap. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Amy Thompson is a Florida-based space and science journalist, who joined Space.com as a contributing writer in 2015. She's passionate about all things space and is a huge science and science-fiction geek. Star Wars is her favorite fandom, with that sassy little droid, R2D2 being her favorite. She studied science at the University of Florida, earning a degree in microbiology. Her work has also been published in Newsweek, VICE, Smithsonian, and many more. Now she chases rockets, writing about launches, commercial space, space station science, and everything in between.