SpaceX's new direct-to-cell Starlink satellites are way brighter than the originals

"If the New Space Age goes badly in the end, history will not look favorably on it."

SpaceX Starlink satellites designed to connect directly to smartphones shine nearly five times brighter in the sky than traditional Starlinks, according to recent research.

SpaceX plans to form what it calls "a cellphone tower in space" with thousands of direct-to-cell (DTC) satellites around Earth that offer service straight to unmodified smartphones "wherever you can see the sky." The higher luminosity of these DTCs compared to regular Starlinks is partly because they circle Earth at just 217 miles (350 kilometers) above the surface, which is lower than traditional Starlink internet satellites, whose altitude is 340 miles (550 kilometers), the study reported.

In January 2024, just a week after placing the first batch of six Starlink DTC satellites in orbit, SpaceX used one of them to send text messages. In May, the company successfully demoed a video call, and said it is working with T-Mobile to roll out such cellular service to customers later this year. There are now over 100 DTC satellites in low Earth orbit, including 13 that were launched last week. Following successful testing of the first batch of DTCs, in March SpaceX requested an amendment to their license with the U.S. Federal Communications Commission that would allow them to operate up to 7,500 DTCs in LEO.

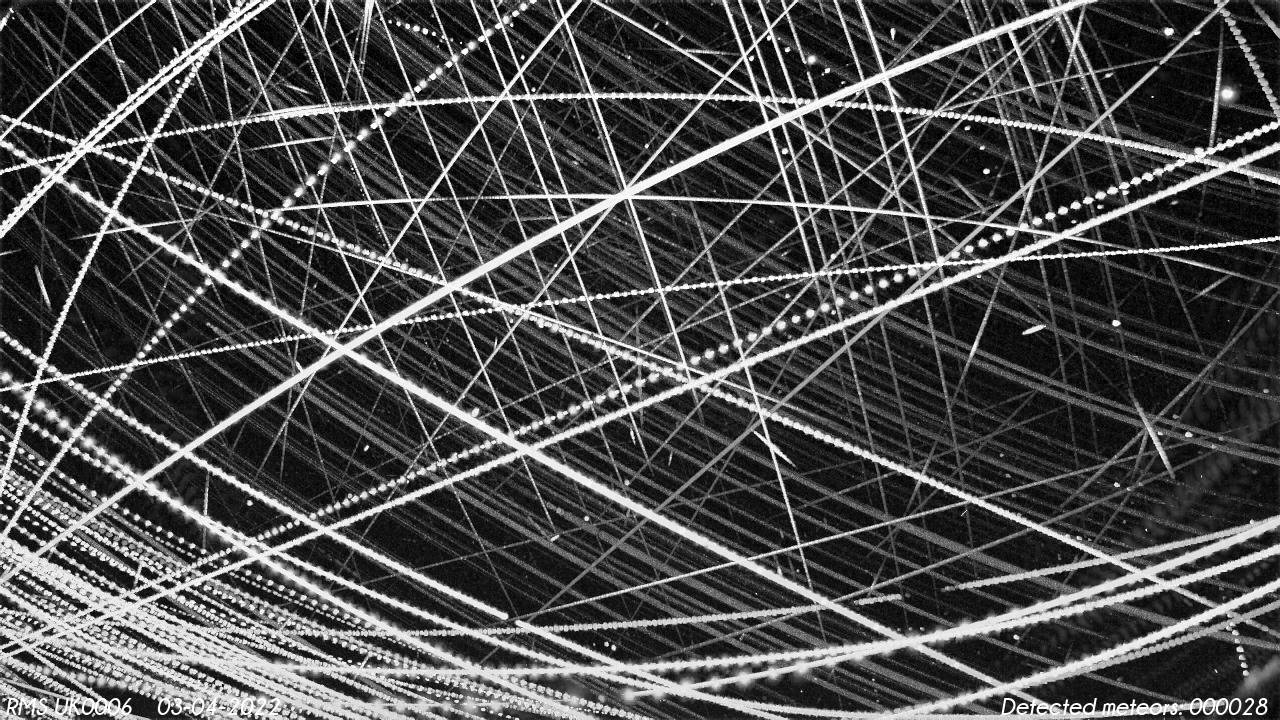

It's always nice waking up to find a #SpaceX #starlink train on the Meteor Cameras from the night before. 🛰️ pic.twitter.com/rGrTAi7KroJuly 28, 2024

At the time the study was conducted, SpaceX had not yet applied its routine brightness mitigation techniques to the DTCs, such as adjusting their chassis and solar panels to reduce the portion of spacecraft illuminated by the sun, study lead author Anthony Mallama of the IAU Centre for the Protection of Dark and Quiet Skies from Satellite Constellation Interference (IAU-CPS) told Space.com.

Related: Blinded by the light: How bad are satellite megaconstellations for astronomy?

Kate Tice, SpaceX senior manager for quality systems engineering, acknowledged during the launch webcast in January that DTC satellites will be brighter than regular Starlinks, and said the company plans to work with astronomers to assess the impact on their observations before making hardware adjustments that would dim the DTCs, SpaceNews reported.

SpaceX began applying brightness mitigation techniques to regular Starlinks in 2020, after astronomers voiced serious concerns about the satellites' trails streaking across telescope images, rendering them unusable. Prior to launch, the company now applies a mirror-like dielectric surface to the underside of each Starlink chassis, to help reflect sunlight into space rather than scattering it toward Earth. Post launch, the company adjusts spacecraft chassis and solar panels to further reduce luminosity. Together, these techniques are very effective, reducing Starlink satellites' brightness by a factor of 10, Mallama said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If SpaceX applies these brightness mitigation techniques to the DTCs, which are nearly the same size as the regular Starlinks, the DTCs would still be 2.6 times brighter than their traditional counterparts, Mallama and his colleagues reported in the recent study, which was reviewed internally by IAU-CPS and posted to the preprint server arXiv last month.

However, while DTCs are brighter objects, they move at a faster apparent rate and spend more time in Earth's shadow than regular Starlinks, which would offset some of their negative impact on astronomy observations, the study noted.

"I see it as a tradeoff in parameters rather than an absolute better/worse kind of situation," John Barentine, a principal consultant at Arizona-based Dark Sky Consulting who was not involved with the new study, told Space.com.

Barentine suspects that radio emissions beamed by the DTCs' antennas may be interfering with radio bands protected for astronomy, as the satellites communicate with Earth via radio signals but don't have a dedicated spectrum to do so.

While scientists agree that providing connectivity to remote regions in the world is a worthy goal, the speed at which satellites are being launched to orbit worries many of them — and not just because of their image-scarring brightness. Over a million satellites may soon enter a space around Earth already crowded with thousands of derelict spacecraft, spent rocket bodies and millions of millimeter-sized pieces of junk that zip above us at high speeds. This debris population poses a threat to satellites that provide internet service, navigation and weather monitoring, and sometimes even to astronauts onboard the International Space Station.

Related: Astronomers urged to fight 'tooth and nail' to protect dark skies

Even if we can dodge a disaster in orbit by responsibly de-orbiting derelict satellites, many scientists are concerned that the number of objects circling our planet could still do harm: When they deorbit, they could deposit a significant flux of metals that could alter the chemical makeup of Earth's atmosphere.

"Effects on astronomy are just the tip of the iceberg," said Barentine, who says we may be fast approaching a turning point where tragedy becomes imminent, either in space due to a collision or on the ground from falling debris. "Space policy-making moves far too slowly to effectively deal with all of this."

"Right now, there's not a lot to look forward to that is positive," he added. "If the New Space Age goes badly in the end, history will not look favorably on it."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

-

mikeash Its always shocking to consider the implications or whats allowed to happen. Its a prime example of the mindlessReply

march into orbit. -

shpoople Reply

These satellites pose little risk of space junk and their effect on the Earth's atmosphere is minimal compared to micrometeorite showers and space dust. While the impact on astronomy is a big negative, it mostly effects the most sensitive telescopes on the ground and space telescopes were always the real way forward on that front.mikeash said:Its always shocking to consider the implications or whats allowed to happen. Its a prime example of the mindless

march into orbit. -

mikeash Reply

I wasn't implying satellites as having effects on the atmosphere. I don't know how you got that idea. Read the OP again.shpoople said:These satellites pose little risk of space junk and their effect on the Earth's atmosphere is minimal compared to micrometeorite showers and space dust. While the impact on astronomy is a big negative, it mostly effects the most sensitive telescopes on the ground and space telescopes were always the real way forward on that front. -

Hugh.Jaynus Article is written and posting in August 2024.Reply

They chose to use a picture from 2019, BEFORE SpaceX instituted measures to address astronomers' concerns. Typical lazy and dishonest "journalism".

Also, the end of the article talks about possible satellite collisions with absolutely NOTHING about the collision avoidance standards put forth by NASA. Again, lazy and dishonest journalism.

NASA recommends that satellites be able to avoid collisions if the possibility of a collision is 1 in 10,000. SpaceX has programmed their satellites with a 1 in 1,000,000 possibility - a 100 fold increase in avoidance sensitivity and awareness.

And the article linked to discuss atmospheric pollution due to space debris is just laughable. Absolutely no talk about any possible natural causes, just that it's all man-made. I didn't know mankind could make lead and copper - pretty sure those are naturally occurring elements on the periodic table. But, as usual, scientists with a biased hypothesis magically find evidence that supports their agenda. Funny how that happens when government funds "science".

Articles like this are why people who follow the space industry and actual science know that space.com is not a reputable source information. It's the equivalent of MSNBC in the "news" industry.