Let's explore the personalities of some of the brightest stars in our sky

If like me, you have been watching the night sky for a long time, you will begin to recognize certain stars and constellations as old friends.

You might even welcome them as they make their first appearance in the eastern evening sky at the start of a particular season, and bid them a fond farewell as they begin to disappear in the west several months later. And with time, you may even learn some of the history and outstanding characteristics of certain stars; like people, no two are really alike.

So, this week, let's explore the personalities of some of the brightest stars in our current evening sky.

Related: The brightest planets in the night sky: How to see them (and when)

More: Night sky, November 2021: What you can see this month

A world's fair 'turn on'

Our first stop is Arcturus in the constellation Boötes, the herdsman, which is now descending the sky slightly north of due west. This orange star of magnitude -0.05 is the fourth brightest star in the night sky and is now known to be 36.7 light-years from us.

But in 1933 astronomers thought it was 40 light-years away.

That year, during the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago, starlight from Arcturus was focused on a photocell attached to the 40-inch (102 centimeters) Yerkes refracting telescope to turn on the lights of the exposition. The astronomers of that time thought they were using radiation that started heading toward Earth in 1893 — 40 years earlier, when the tube and mounting of this giant telescope went on display for the general public at the World's Columbian Exposition in the same city.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Arcturus is a giant star: Although it's roughly the same mass as our sun, it is about 25 times larger and 170 times more luminous.

Related: The Brightest Stars in the Sky: A Starry Countdown

Say cheese

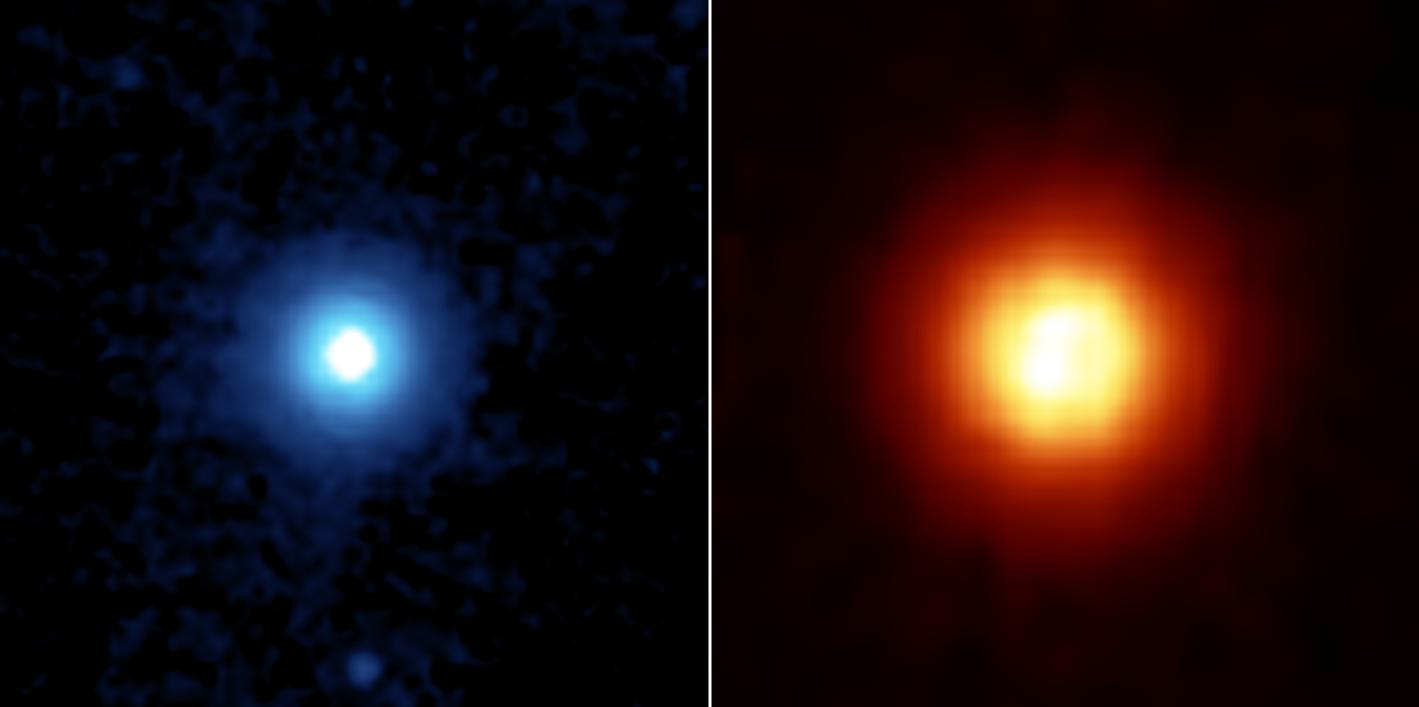

Just to the west of the zenith (the point located directly overhead) is brilliant Vega in the constellation of Lyra, the lyre. At magnitude +0.03 it is just a trifle fainter than Arcturus, yet its blue-white color makes it appear brighter to many people.

On July 17, 1850, Vega became the first star to ever be imaged, when it was captured by William Bond and John Adams Whipple at the Harvard College Observatory using the daguerreotype process. Vega was also one of the first stars to have its distance measured using a process known as trigonometric parallax, which was calculated by Wilhelm von Struve in the 1830s.

At a distance of only 25 light-years from Earth, it is one of four fairly close stellar neighbors. It's about twice as massive and two-and-a-half times larger than the sun, and 40 times more luminous.

Among the most dazzling

In contrast, Deneb in the constellation Cygnus, the swan, is perhaps 2,600 light-years away — so far away that its distance can't be measured trigonometrically.

Nevertheless, Deneb still manages to be ranked among stars of the first magnitude (magnitude +1.25) due to its high intrinsic luminosity, which is about 5,000 times greater than Vega's, placing it among the visually brightest stars known. It's the19th brightest star in the sky and is quite similar to many of the hot young stars that illuminate our winter sky, such as Rigel in Orion, the hunter.

An "outstretched" sun

The closest bright star in our current evening sky is Altair, a mere 16.7 light-years away. Fewer than 50 stars and multiple-star systems are known to be nearer.

Altair is the brightest luminary in the constellation Aquila the eagle at magnitude +0.77, and forms the famous Summer Triangle along with Vega and Deneb. It's nearly twice as massive as our sun and 11 times as luminous.

Interestingly, while our sun takes about 25 days to make a complete turn on its axis, Altair's rotational period takes just nine hours. As a result of this rapid spin, Altair's shape is an oblate spheroid and is noticeably flattened at both poles.

A colossal stellar beacon

Low in the southwest, we can see Antares, in the constellation Scorpius, the scorpion getting ready to leave the evening sky. If the sun was at the center of this immense supergiant, Earth's orbit would be inside the star; it is one of the largest stars visible to the unaided eye.

Antares is quite far away (about 600 light-years) and usually shines at magnitude +0.9, but it can vary by several tenths of a magnitude at irregular intervals.

Lonely and dusty

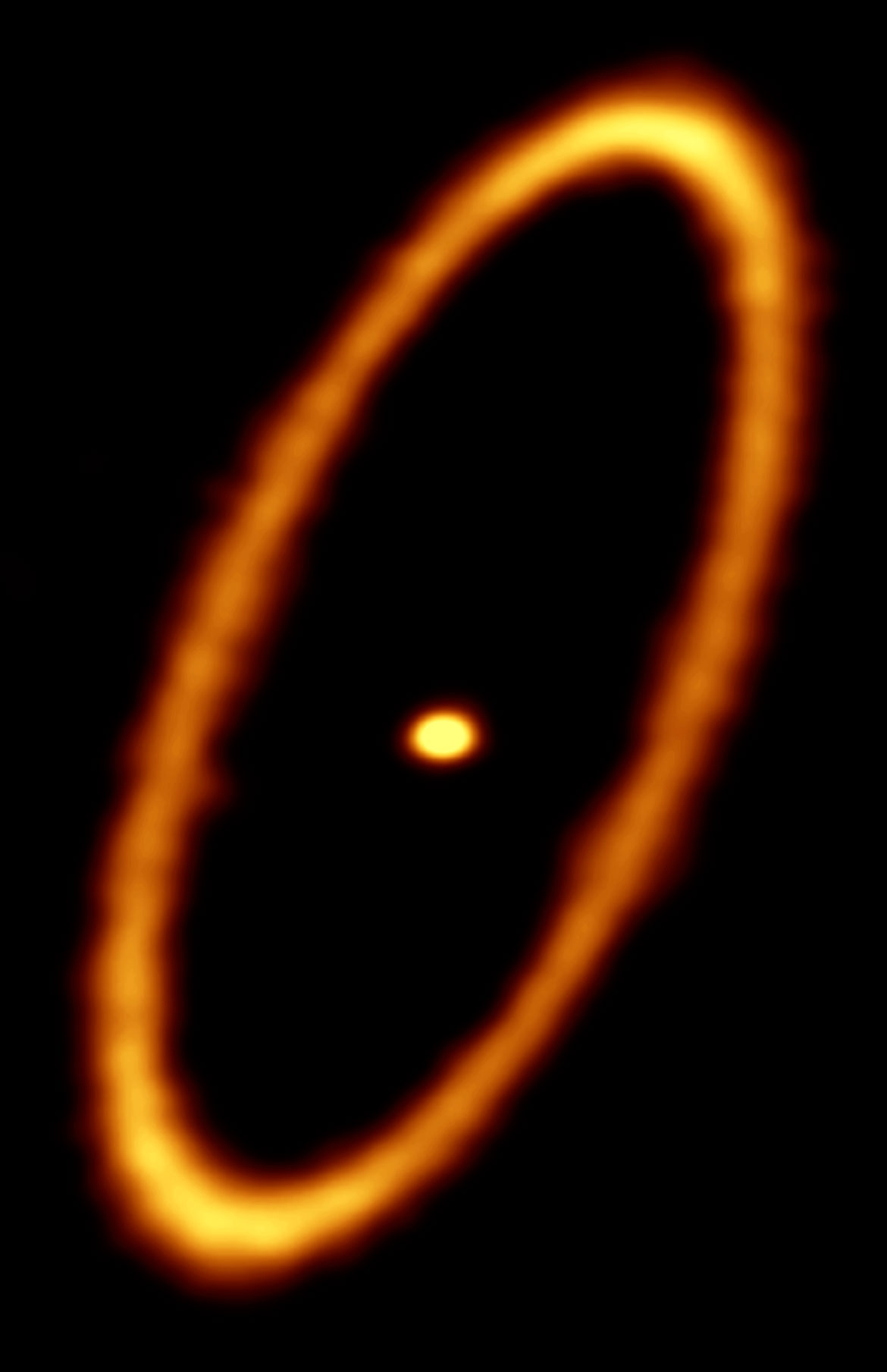

At the mouth of Piscis Austrinus, the southern fish, lies Fomalhaut, the only bright star in the so-called "watery" part of the sky. The lack of bright stars nearby makes Fomalhaut seem much more conspicuous than its +1.16 magnitude suggests, and is why it's sometimes referred to as the "solitary one."

Fomalhaut is 25 light-years away and is nearly twice as large as the sun and about 17 times more luminous. It is also apparently surrounded by a disk of dust and debris, which in 2008 was believed to be an extrasolar planet (designated Fomalhaut b, and later, in 2014, named Dagon).

Here comes winter!

Finally, the harbinger of the brilliant winter parade has made its appearance in the northeast for observers in mid-northern latitudes. If you lie north of +44 degrees, Capella is circumpolar — that is, it never rises or sets but makes a circle around Polaris, the North Star, and is visible throughout the entire year. It is the most sunlike of autumn's bright stars; an exceedingly close double star whose components are slightly cooler but substantially brighter and more massive than our own star.

Capella is 42.9 light-years away, and at magnitude +0.08 it is only slightly fainter than Vega. In addition, Capella and Vega are on opposite sides of the pole, at about the same distance from it — an imaginary line between the two stars would nearly pass through Polaris. When one star is high, the other is low, and as we turn the corner toward the fall, Vega is high overhead while Capella is only now just emerging into view.

But come three months from now, when it will certainly be much colder, it will be Capella near the top of the frosty skies during mid-evening, while Vega is about to drop out of sight in the northwest.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.