One of the respected luminaries of the "Star Trek" universe is seven-time Emmy Award-winning visual effects supervisor, matte painter, prop maker, title designer, and storyboard artist Dan Curry, whose 18-year body of work on "Star Trek: The Next Generation," "Deep Space Nine," "Voyager," and "Enterprise" contributed myriad elements to the shows' integrity and evolution.

A Tai Chi master who has traveled the globe, Curry also created the Klingon martial arts style named Mok'bara and the warrior race's distinctive Bat'leth and Mek'leth weapons.

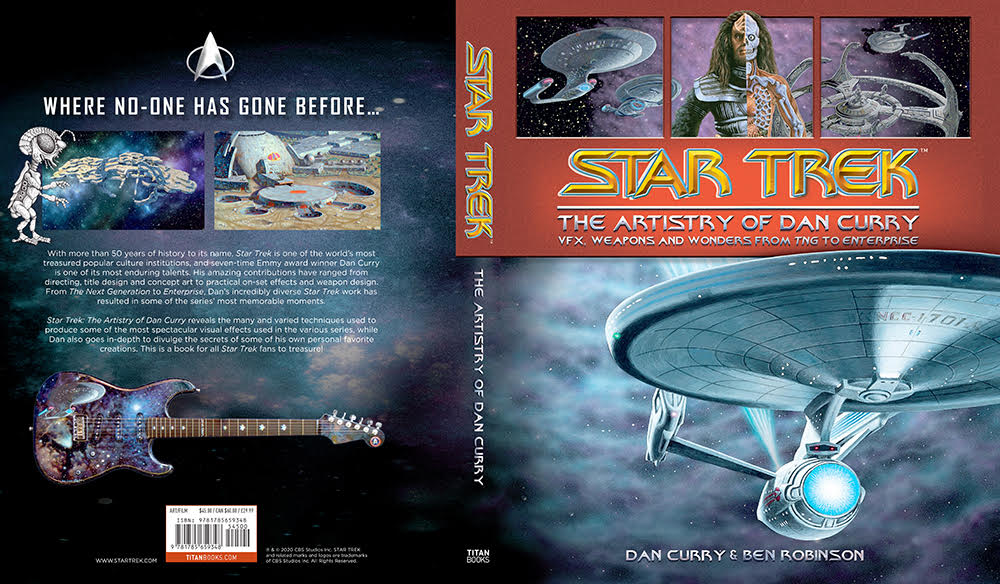

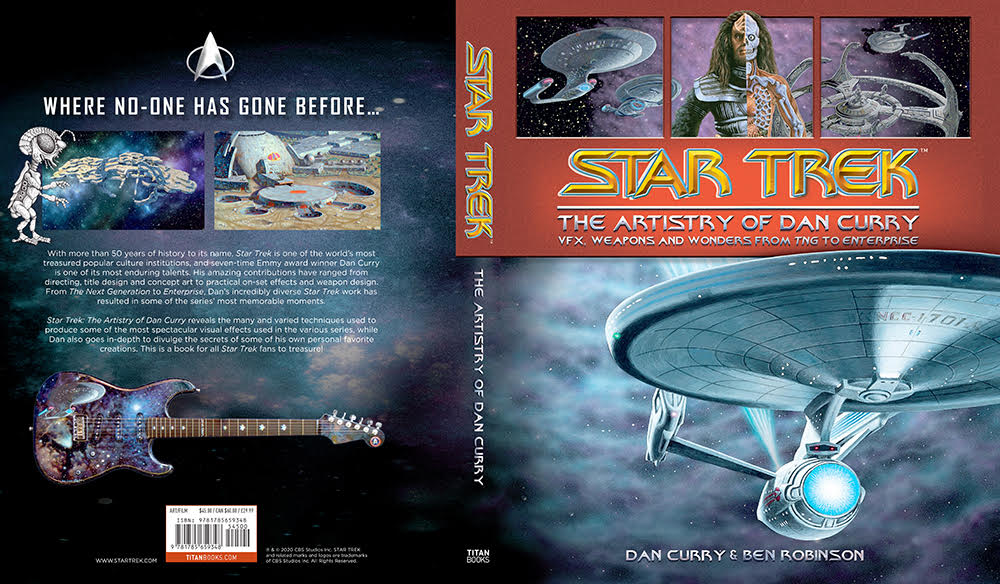

In honor of Curry's innumerable accomplishments over the course of his illustrious career, a deluxe new coffee table book titled "Star Trek: The Artistry of Dan Curry" (Titan Books, 2020) beams to Earth orbit on Dec. 1.

Co-written with author Ben Robinson, this 204-page hardback spotlights the achievements of one of "Star Trek's" most valued alumni, with rare concept art, behind-the-scenes stills, and secrets to how Curry and his colleagues created the impressive legacy of special effects magic.

We spoke with Curry regarding this rich retrospective of his time on "Star Trek," what he loved most about the series' starships, how time in the Peace Corps influenced Klingon culture, memories of Gene Roddenberry, and how he helped create the Star Trek Stratocaster guitar.

Space.com: Looking back on your "Star Trek" career, what are some defining moments that stand out?

Dan Curry: The first outstanding moment was my first day walking on "The Next Generation" set. The cast was there in costume and the crew was on the beautiful sets designed by Herman Zimmerman. The outsides of the sets are thin plywood walls with two-by-two wooden frames that support them. When you go from outside the set on the soundstage with its concrete floor, lights, gear, and people hanging around, then walk through a door and suddenly you're in the 24th century.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

I asked one of the crew members who the captain was and he said, "Oh, that bald guy over there." Then Patrick [Stewart] came out and delivered his first line. He was the captain. I was immediately aware that I was in the presence of a truly great actor.

Space.com: Being such an influential part of four “Star Trek” series, why do you believe the franchise is so resilient and revered?

DC: Well, that goes back to Gene Roddenberry's genius and his vision. I think the enduring appeal of "Star Trek" is that it promises a future where our species has it together in terms of conquering poverty, racism, and developing a truly comfortable relationship with our own technology, which has yet to happen in today's world. I think what makes the appeal of "Star Trek" is that future.

I also think there are issues like the Prime Directive, which was Gene's response to the colonialism of the 19th century, where more advanced nations would just show up with their better technology, plant a flag, and feel they had the right to control them.

The Prime Directive stated that if the crew of a Federation starship encounters a more primitive species then we should not use our technology to change who they are and what their culture is. People want to believe we can evolve into a species where individuals are free to develop themselves to the best of their ability. That's always been the promise of our country, and has yet to be achieved. The dream of that halcyon future keeps audiences coming back.

Space.com: What was your gateway into sci-fi and which Hollywood movies struck a nerve?

DC: I've always been a science fiction fan, even as a little kid I had spacemen toys, toy spaceships and enjoyed making my own spaceships, which I ended up doing on "The Next Generation" a lot. Important films for me were "Earth vs. The Flying Saucers" and "The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad," where I could tell that there were different levels of reality within the image.

After seeing "The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms" and reading how it was done, I made a crude rear-projection system by taping tracing paper inside a cardboard box and rear projecting images of my brother running around pretending to be chased by dinosaurs, and in the foreground, one frame at a time, stiffly moving toy dinosaurs. That was my first endeavor in visual effects.

But the most significant film for me was "Forbidden Planet," which was the first big-budget, cerebral, science fiction epic that influenced every science fiction film of stature to come. Even as a boy watching it, I could tell there were paintings, there were models, cartoon animation, and they all blended together to create a new cinematic reality and that's what I wanted to do.

Another film, which led to me doing over one-hundred title sequences, was “Spartacus.” Saul Bass' brilliant work made me aware of the power of the title sequence.

Space.com: In all the series you worked on, which Federation Starship was your favorite and why?

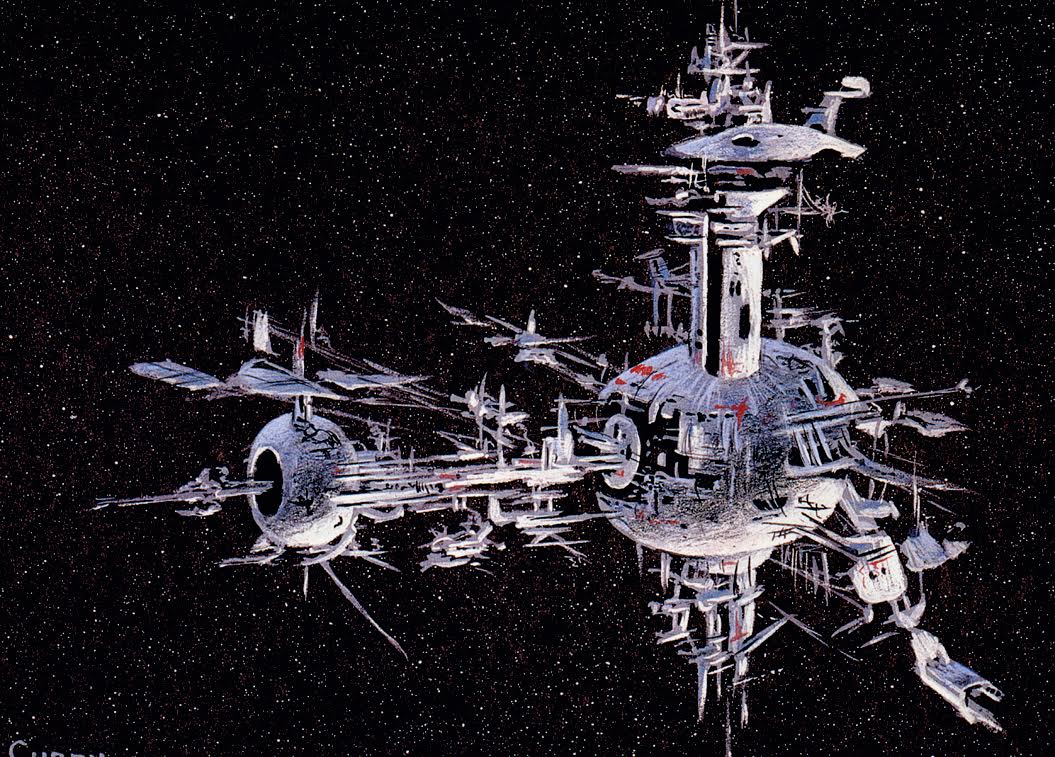

DC: That's difficult to determine. They all owe a debt to Matt Jefferies' innovative Enterprise-1701 for the original series. That combination of the classic flying saucer with other superstructures, and of course the parallel warp drive nacelles.

The Enterprise-D, designed by Andy Probert under production designer Herman Zimmerman's supervision is elegant, and beautifully fluid. I always loved photographing that ship and just being in the presence of the beautiful models of the 1701-D. First, the one made by the team at ILM, then the four-footer made by Greg Jein. I always loved that ship.

Then "Deep Space Nine" arrived, also designed under the supervision of Herman Zimmerman. That model was constructed by the great model maker Tony Meininger. I fell in love with that station the first time I saw the rough plywood mockup.

"Voyager" came along, primarily designed by Rick Sternbach under production designer Richard James' supervision. That was a smaller, sleeker starship that had all the classic Federation elements like the twin nacelles and the main saucer shape, although in Voyager's case it was like an upside-down spoon.

Finally, the Enterprise NX-01 for "Star Trek: Enterprise," that ship was definitely one of my favorites. That was the first time we didn't have a physical model as it was an all-digital show. Kudos to Pierre Drolet who built the digital model. He put so much love into it with incredible detail so we could get really close to it on screen.

Choosing a favorite ship is like being asked which child you like best. You love them all and appreciate their differences.

Space.com: Do you own any prized mementos kept from the TV shows?

DC: Not much. It was frowned upon. Anything I wanted, I'd ask the producers for. I do have Bat'leth #1 and Mek'leth #1 and I have a little hand prop from "Deep Space Nine," a Cardassian device like an alien iPad that has my face on it as a deceased mad scientist. I have some of the shards left over when we'd blow up a model. Sometimes I'd make space debris made out of plastic parts melted over a candle. If we came upon a destroyed spaceship, the random plastic parts would be the debris that would fly by. I did keep a lot of my storyboards and concept sketches.

Space.com: What do you remember about your interactions with Gene Roddenberry?

DC: Well, we would talk a lot about visual effects but many of our personal discussions were philosophical … talking about what he felt were important themes for the show. One very fond memory was going to visit the mockup of the International Space Station. My son was quite young at the time and I brought him along. Gene at that time was in a wheelchair he'd ride around in. My son got tired so he toured the space station riding on Gene's lap chatting with him.

I also enjoy my friendship with Gene's son, Rod, who was an intern in the visual effects department while he was in high school. Rod has taken the legacy of his father's creation in a very honorable direction and does a lot of philanthropic work. He's someone who has earned my respect over the years by being a really great person.

Space.com: "Voyager" celebrates its 25th anniversary this year. How was that an important series in the development of the "Star Trek" franchise?

DC: It broke some ground by having a female captain. Kate Mulgrew took the job very seriously and took courses in science so she'd have a real grasp of what her character was all about. It was a very enjoyable cast to work with. I had a great opportunity to oversee the design of the title sequence as well. The producers were very busy, so I had the chance to pick out dream places I'd like to go if I was in space. Doing that title sequence was one of my happiest experiences. Jerry Goldsmith’s inspiring theme music gave the visuals majesty.

I really liked the premise of being in an uncharted part of our galaxy, the Delta Quadrant, so we could do all sorts of new things because we could encounter species that were new to the franchise. One of my favorite episodes was, "Basics Part 1 and 2," where our crew was marooned on a planet inhabited by primitive neolithic people. We got to create lava streams and volcanos, and a cave monster that ate our stunt coordinator Dennis Madalone. That was great fun

"Voyager" took on a lot of interesting themes. I liked the holographic doctor, brilliantly portrayed by Bob Picardo. It was a fresh look at the "Star Trek" universe, but from a different perspective.

Space.com: Can you tell us about your guitar-making hobby and that stunning "Star Trek" guitar?

DC: My colleague Ron Moore, who started as visual effects coordinator working with me, and then became visual effects supervisor, is also an excellent guitarist. He had the idea to do an art guitar. So we went down to Corona, California and had meetings with the Fender people. They sent me some guitar parts and we decided to go with the Stratocaster pattern.

I got home and started laying out the guitar and drawing things on it. George Amicay, Fender's master carver, carved the ships in high relief, primed the guitar, then sent it back to me. I did the final painting. Then Alan Hamel, head of the Fender Custom Shop, personally did all the electronics. It may be the only Fender Stratocaster without a separate pick guard because I wanted a seamless canvas to work on. It was in the Fender Museum for years.

Space.com: How did your time in the Peace Corps and travels though Asia influence some of the Klingon culture seen in the shows?

DC: After college I volunteered for the Peace Corp and was assigned to community development in northeast Thailand building small dams and bridges on tributaries of the Mekong River. I found out that each village had a generations-old, secret martial art they would practice. In ancient times they had no outside help to defend themselves from marauders. I began my interest in martial arts at that time, but also my interest in the architecture of Laos and Thailand and Nepal.

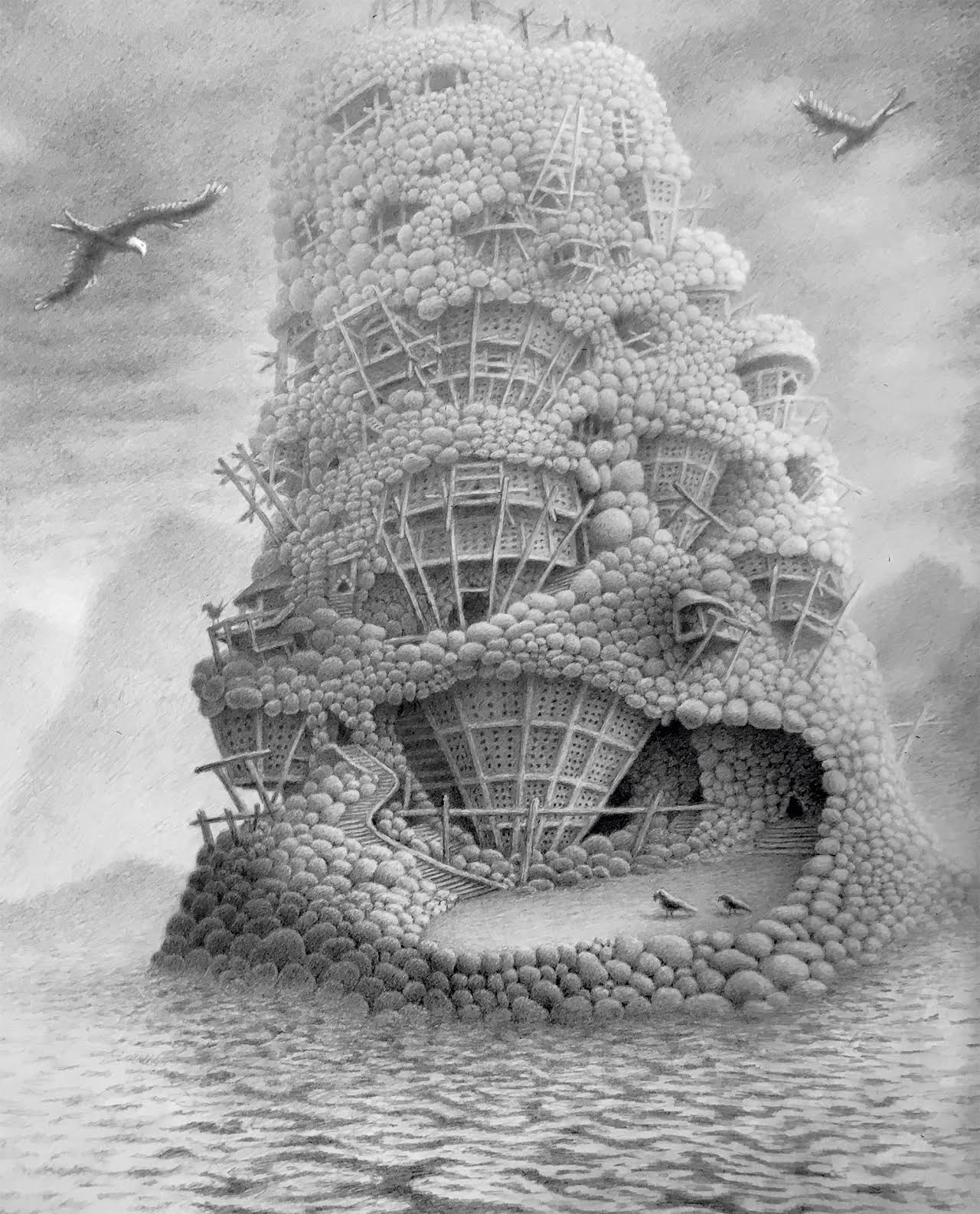

So when you see exteriors of Klingon cities or Klingon outposts, most of them were matte paintings by the great Syd Dutton. I'd work with him on evolving a style that was a composite of Thai, Lao, and Nepali architecture. I did some of the matte paintings myself, like the Klingon Lamasery, which is a Tibetan-looking building on a mountaintop inspired by a train trip I took through the Canadian Rockies.

When we had an episode where Worf was to inherit a bladed weapon, the art department sent down a weapon that looked like a pirate's cutlass. It was cool, but familiar. I felt we needed to do something better than that. I'd been imagining a weapon for years, but never had a reason to bring one into existence. I made one out of foam core and that became the Bat'leth.

Space.com: If given the keys to the kingdom for any "Star Trek" show, where would you take it?

DC: That's an interesting question. I would want to go with a new ship and a new crew like the people doing the current "Star Trek" shows. Make it optimistic but serious about exploration and stress the potential for humanity to reach a higher level of enlightenment.

"Star Trek" realized its responsibility to not only inspire but educate their audience, and be a source of inspiration about relating ourselves to other species.

Space.com: How did being part of "Star Trek" affect your life as an artist, husband, and father?

DC: I had lots of opportunities to go off and do other features but I decided to stay with "Star Trek" because I felt part of the family. I was a member of the 18-year club of people that stayed with it from the beginning of "The Next Generation" to the end of "Enterprise."

My son grew up visiting the sets and knowing everybody. Until "Enterprise" ended, there was never a time when "Star Trek" wasn't a part of his life. One of the things I tried to stress with him growing up was that the principal characters always tried to make the right and honorable decision when confronting adversity. For me "Star Trek" was something I felt was a calling that became important to me to be a part of that legacy.

The illusions that created the universe of "Star Trek" were the result of many gifted and dedicated artists. There was no single hero of its visual effects. I was very fortunate to design and create a lot of things that became part of the "Star Trek" franchise. I feel it was a decent legacy to leave behind when I ultimately move into the non-biological phase of existence.

Titan Books' "Star Trek: The Artistry of Dan Curry" is available on Dec. 1.

Editor's note: All images from Star Trek: The Artistry of Dan Curry by Ben Robinson & Dan Curry provided by publisher by Titan Books. © 2020 CBS Studios Inc. © 2020 Paramount Pictures Corp. Star Trek and related marks and logos are trademarks of CBS Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jeff Spry is an award-winning screenwriter and veteran freelance journalist covering TV, movies, video games, books, and comics. His work has appeared at SYFY Wire, Inverse, Collider, Bleeding Cool and elsewhere. Jeff lives in beautiful Bend, Oregon amid the ponderosa pines, classic muscle cars, a crypt of collector horror comics, and two loyal English Setters.