Amateur astronomers capture groundbreaking photos of sun's corona during partial solar eclipse

"Most people just dismiss partial eclipses. But I wanted to go to this partial eclipse to try to get the corona — and I did it! This has opened the door to new dreams and challenges."

In an achievement that defies conventional wisdom among astronomers, a trio of eclipse chasers has captured what experts confirm is the first documented observation of the solar corona during a partial solar eclipse.

The remarkable images — taken from Quebec, Canada, during the March 29, 2025, partial solar eclipse — reveal the sun's outer atmosphere — a feature typically visible only during the brief moments of totality during a total solar eclipse.

"The corona is often captured during the partial phases of annular and total eclipses, but no one ever tried to capture it during a partial eclipse," exclaimed Mike Kentrianakis, an eclipse chaser and astrophotographer from New York City. Kentrianakis, a veteran of 29 solar eclipses and known as the "Oh my God!" guy for his viral Alaska Airlines video in 2016 (plus the addictive remixed version), observed the eclipse at sunrise from the shoreline at Les Escoumins, Quebec, on the north side of the St. Lawrence River, with fellow eclipse chaser Kevin Wood.

While shivering in temperatures of 14 degrees Fahrenheit (minus -10 degrees Celsius), they appear to have captured the inner corona silhouetting the moon .

"It's a really interesting observation that could be repeated in the future," said Matt Penn, a solar physicist and adjunct assistant professor at Southern Illinois University Carbondale who has studied the corona extensively. "It's something that could be used to study the corona in a new way."

Related: Partial solar eclipse delights skywatchers around the world (photos)

Where and when the corona was captured

The location was no fluke. They shot video of the sun rising at 6:22 a.m. EDT while it was already 87% eclipsed, having used astronomy apps — including PeakFinder and PhotoPills — to make sure they would see something very unusual. But it wasn't the corona they were looking for. Rather, they wanted to snap the two 'horns' of the sun appearing on the horizon separately on each side of the moon's silhouette.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"I call them solar headlights — it was like there was a great car headed toward me out there; it was phenomenal," said Kentrianakis, who later posted a video, initially just showing this unique "double sunrise" effect.

Then, he noticed something unexpected in his shots: traces of the solar corona. That was uploaded, too, and then processed color and monochromatic versions. Another photographer who stopped by their location, Jason Kurth, later posted images of the faint solar corona on Instagram and a video of the sunrise on YouTube, which was featured as NASA's "Astronomy Picture of the Day" on April 1.

Why the corona looks like a ring

No one else who photographed the eclipse captured the dark portion of the moon silhouetted against the light of the solar corona. To be clear, this was a photographic corona; no one saw it with their own eyes.

The impression of a ring around the lunar limb results from a contrast in brightness. "Near the surface of the sun, in the low corona, it's very bright, and you can see that during eclipses — it's comparable to the brightness of the surface of the full moon," Penn said. "But as you go even just one solar diameter away, it drops by a factor of 100 or 300 in intensity, so the corona has a very steep intensity gradient."

Explaining the corona

Until recently, astronomers and eclipse chasers assumed that the solar corona could be observed only during the totality phase of a total solar eclipse, when the moon completely blocks the sun's bright disk, or photosphere.

"The corona is something like a million times fainter than the everyday sun that we see in the sky," said Dan Seaton, a solar physicist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, who specializes in coronal observations.

This extreme difference in brightness between the corona and the photosphere has historically made observations of the corona impossible outside of totality. Even during the partial phases of a total eclipse, the remaining sliver of the sun's disk is still bright enough to overwhelm the faint corona.

The importance of light scattering

We don't see the corona during the day because of an effect called Rayleigh scattering. "The light from the sun scatters in the atmosphere, and the atmosphere is so much brighter than the corona, so it's just not visible," Seaton said.

It's why the sky is blue and why sunrises and sunsets look red. "Scattering in the Earth's atmosphere turns out to be much brighter in every location on the planet than the corona itself," Penn said. "So the light that's reflected off atmospheric dust gets scattered into your eyes."

However, Penn added, the overall intensity of that light not only overwhelms the corona but also fluctuations caused by noise in that signal. "Unless you're at a really high-altitude site with a coronagraph telescope that handles and controls scattered light very carefully, you're not going to see the corona from the ground at all, except, of course, during a total solar eclipse," Penn explained.

So, why was the corona visible? "If there's a lot of dust and scattering, not only does it scatter the light from the solar sphere, but it also blocks the light that would be coming from an object like the moon — or the corona," Penn said. "They had low scattered light, and the transmission was high enough."

That was mostly about the location and timing. "They determine whether or not the photosphere is visible, and whether or not they got the chance to see the corona without the photosphere swamping it," Penn said.

What made this unprecedented observation possible was likely a perfect convergence of conditions over the St. Lawrence River. "Out over this large body of water, the air is very still and pretty clean — there's not a lot of dust," Seaton said. "It was the best atmospheric conditions you could have."

The deepness of the eclipse — about 88% as the sun rose — was also key. "That reduces the shadow still darkening the sky — not nearly as much as it would during a total eclipse, but it's still reducing the sky brightness by a factor of 10," Seaton said.

By positioning himself so precisely, Kentrianakis effectively used Earth itself as a second occulting disk, blocking the brightest portion of the sun and allowing only the corona to be visible above the horizon. There were also some clouds in the far distance, which may have shaded the sky just enough to allow the corona to be visible up to 20 seconds after the appearance of the "car headlights" at the moment of sunrise.

The timing of this eclipse coincided with solar maximum — the peak of the sun's 11-year activity cycle — which likely provided an additional advantage. "We're at solar maximum right now," Seaton said. "So the corona is brighter than it would be at solar minimum, and it's more distributed around the sun, so there's more corona to see." There was a slightly larger target to capture.

Taking the shot

Meticulous planning was at the heart of this achievement. "I was looking at the map, and I said, 'Wait a minute; the sun is rising in the Northeast, and the eclipse is happening in the Northeast,'" Kentrianakis said. "And I thought, 'If the sun is rising eclipsed, and the sun is 88% covered, that means the bright part of the sun is below the horizon — and the corona is above the horizon!'"

This rapid decrease in brightness means that even with perfect conditions, capturing the corona requires precise exposure settings and equipment. Kentrianakis used modest gear — a Canon M100 mirrorless camera with a 15-200 mm lens. Kentrianakis had to do a lot of bracketing, taking lots of shots using many different exposures.

Related: How to photograph a solar eclipse

"I didn't know what I was going to get; I didn't know if I was going to get anything at all," he said.

Where this partial eclipse was total

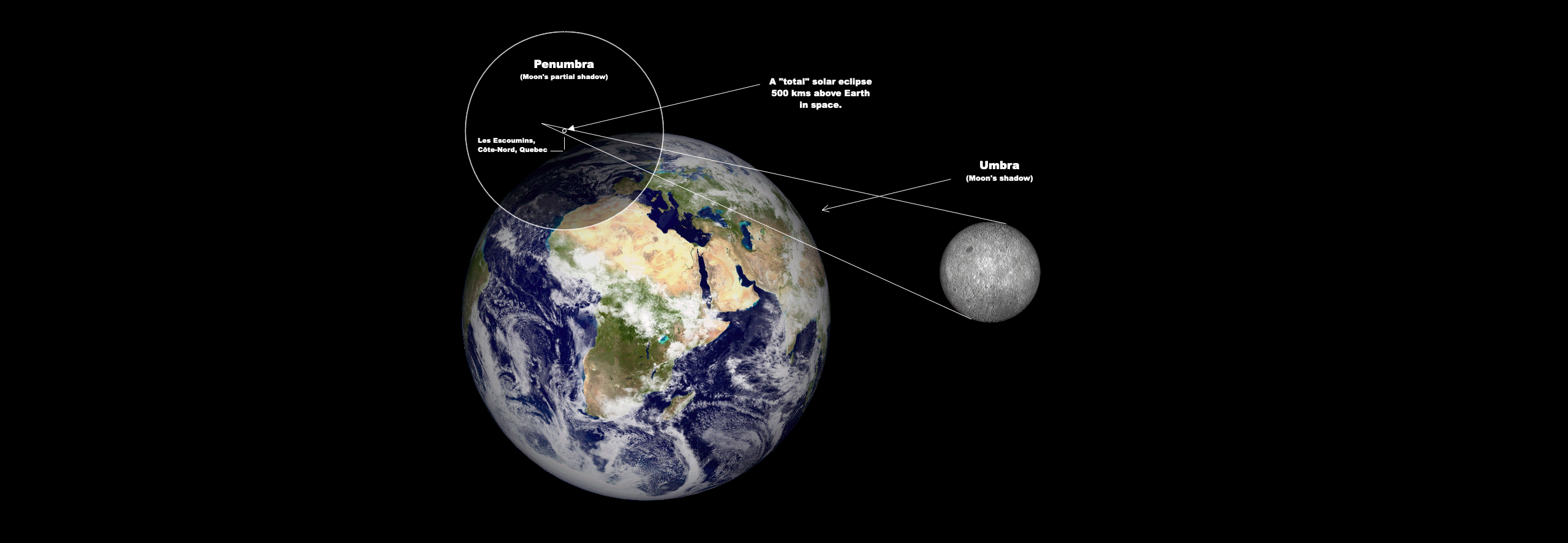

As Kentrianakis and others were shooting a partially eclipsed sunrise, a total solar eclipse was going on above their heads. When a deep partial eclipse occurs on Earth, a total solar eclipse must be occurring just above it. After all, the moon is always projecting a shadow into space — what astronomers call an umbral cone. It's only when Earth moves through this shadow that any kind of eclipse can occur.

According to Mariusz Krukar, an astronomer at Astro-Geo-GIS who remotely observes solar eclipses (including the April 8, 2024, eclipse from Spain), a total solar eclipse was visible 315 miles (507 kilometers) above Les Escoumins — just above the orbital height of the International Space Station.

Views of the solar corona from Earth should not have been possible. "I drove twice as far as the umbra was above my head — 675 miles [1,086 km] one way to see a 'totality' pieced together by the moon, Earth's horizon and clouds," Kentrianakis said.

Eclipses come in families called saroses, with each member separated by 18 years, 11 days and 8 hours. Each saros begins as a slight partial eclipse and, over many centuries, can become a total eclipse. The March 29 eclipse was in Saros 149, whose next member is a total solar eclipse for Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula on April 9, 2043.

This photographic breakthrough could present new challenges and opportunities for observations of the corona during future partial eclipses. The capturing of one of the sun's most elusive features is bound to inspire others to chase partial eclipses, particularly those occurring at sunrise or sunset, Seaton said.

"My sincere hope is that the stuff that Mike has done is going to be something that other people will get excited about and maybe try to improve on," Seaton said. "Ordinary people who are not professional astronomers creating opportunities to see something that's rare is a way of engaging the public with these really rare astronomical phenomena."

Seaton was the lead author of a paper describing observations of the corona in polarized light during the annular solar eclipse on Oct. 14, 2023. "We also published the plans to 3D print a coronagraph that anybody could use to build their own and go to any partial eclipse and give this a try," Seaton said.

When is the next partial solar eclipse?

Eclipse chasers who want to attempt this achievement will have to go to great lengths. The next time it will be possible to observe a partially eclipsed sunrise will be on Sept. 21, 2025, when a 72% eclipsed sun will rise — but that will be the view from the Southern Cross Subglacial Highlands in Antarctica. After that, there will be a chance to see a 70% eclipsed sunrise from western Canada on Jan. 14, 2029.

The capturing of the solar corona — one of nature's most beautiful and mysterious phenomena — during a partial eclipse is a reminder that there are still discoveries to be made, and scientific expeditions and adventures to be had. For Kentrianakis, eclipses are all about the excitement of the expedition and the thrill of the chase.

"Most people just dismiss partial eclipses,” he said. "But I wanted to go to this partial eclipse to try to get the corona — and I did it! This has opened the door to new dreams and challenges."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jamie is an experienced science, technology and travel journalist and stargazer who writes about exploring the night sky, solar and lunar eclipses, moon-gazing, astro-travel, astronomy and space exploration. He is the editor of WhenIsTheNextEclipse.com and author of A Stargazing Program For Beginners, and is a senior contributor at Forbes. His special skill is turning tech-babble into plain English.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.