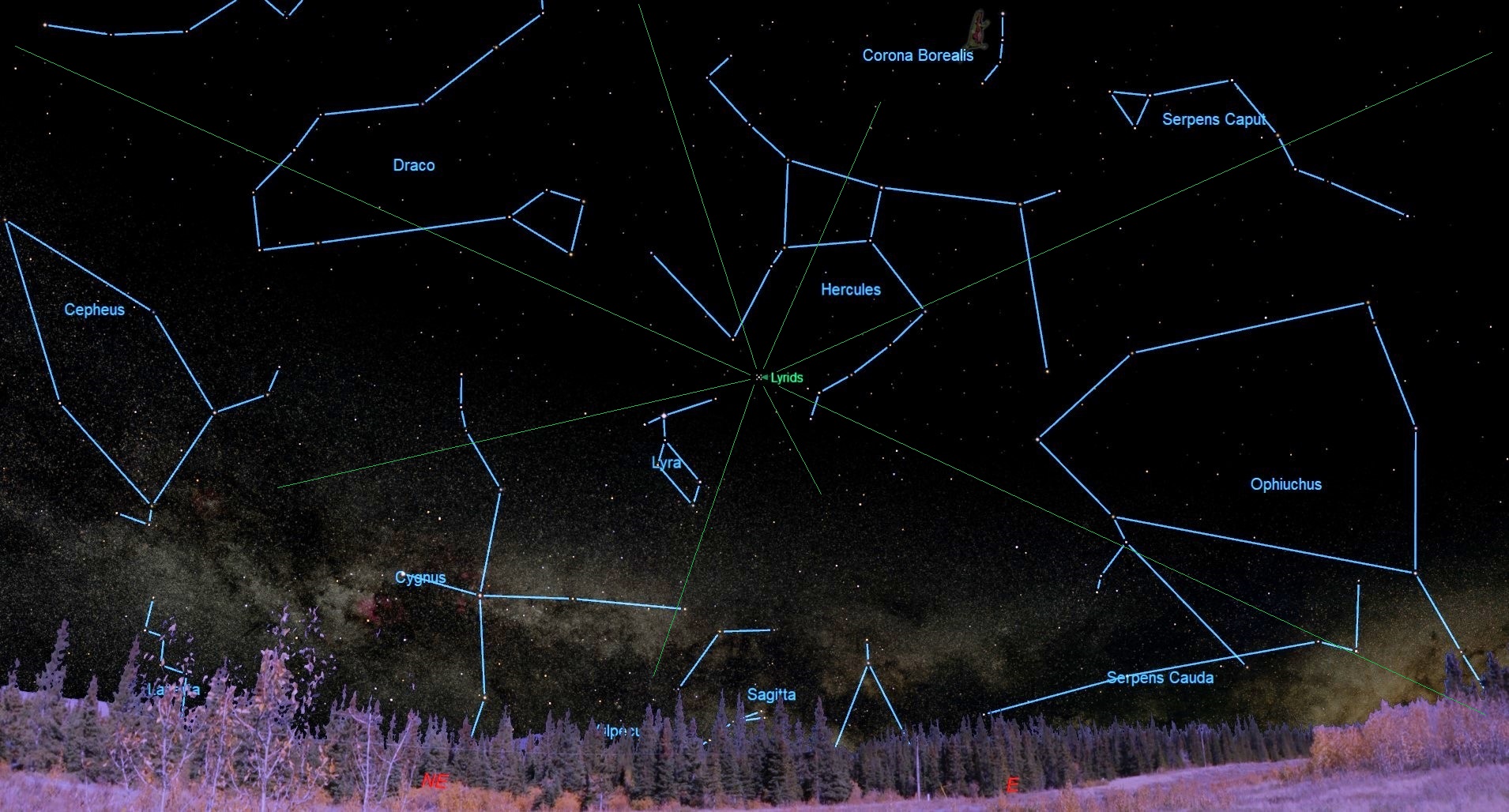

After a lull of some three and a half months, enthusiasts who watch the night sky specifically for "shooting" or "falling" stars will have something to look forward to this month. It will be the return of a faithful meteor shower, recognized as one of, if not the oldest known meteor display: the Lyrid meteors.

While there are many dozens of meteor showers that occur during the course of the year, only ten are recognized as the 'principal' or very best meteor displays. The last such shower to take place was the Quadrantids back on Jan. 3. But since then, there have been no other noteworthy meteor showers to look for so far this year.

That will change soon thanks to the Lyrid meteor shower.

Dutch-American meteor expert Peter Jenniskens refers to the Lyrids as "The proverbial swallow of spring for observers in the northern hemisphere." This, he adds, follows "the low meteor rates in the cold months of February and March."

This is a good year for observing the annual Lyrid meteor shower. Its peak should come on Tuesday morning, April 22, when moonlight will pose little interference. This year, the moon will be in a waning crescent phase, only 36 percent illuminated and will not rise until around 3:30 a.m. local daylight time.

Peak time uncertain

But although the Lyrids are a reliable meteor display, they nonetheless come with a disclaimer: They are often elusive; their surge of activity usually lasts just a few hours at most. According to the 2025 Meteor Shower Calendar of the International Meteor Organization (IMO), the time of maximum activity is anticipated to come at around 1330 Universal Time (UTC) or 9:30 a.m. ET. This is based on results collected from observations spanning the years 1988 to 2000. That predicted time would favor those living in Hawaii where predawn skies will be dark, as opposed to the contiguous U.S. where the sun will have already risen.

However, in more recent years the time for the Lyrid peak has been more variable and if applied to this year, it might come as early as 10:30 UT to as late as 18:00 UT. If the former time rings true this year, it would mean that those living in the Mountain and Pacific time zones of the western U.S. would have an advantage in that the peak would come before the start of morning twilight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

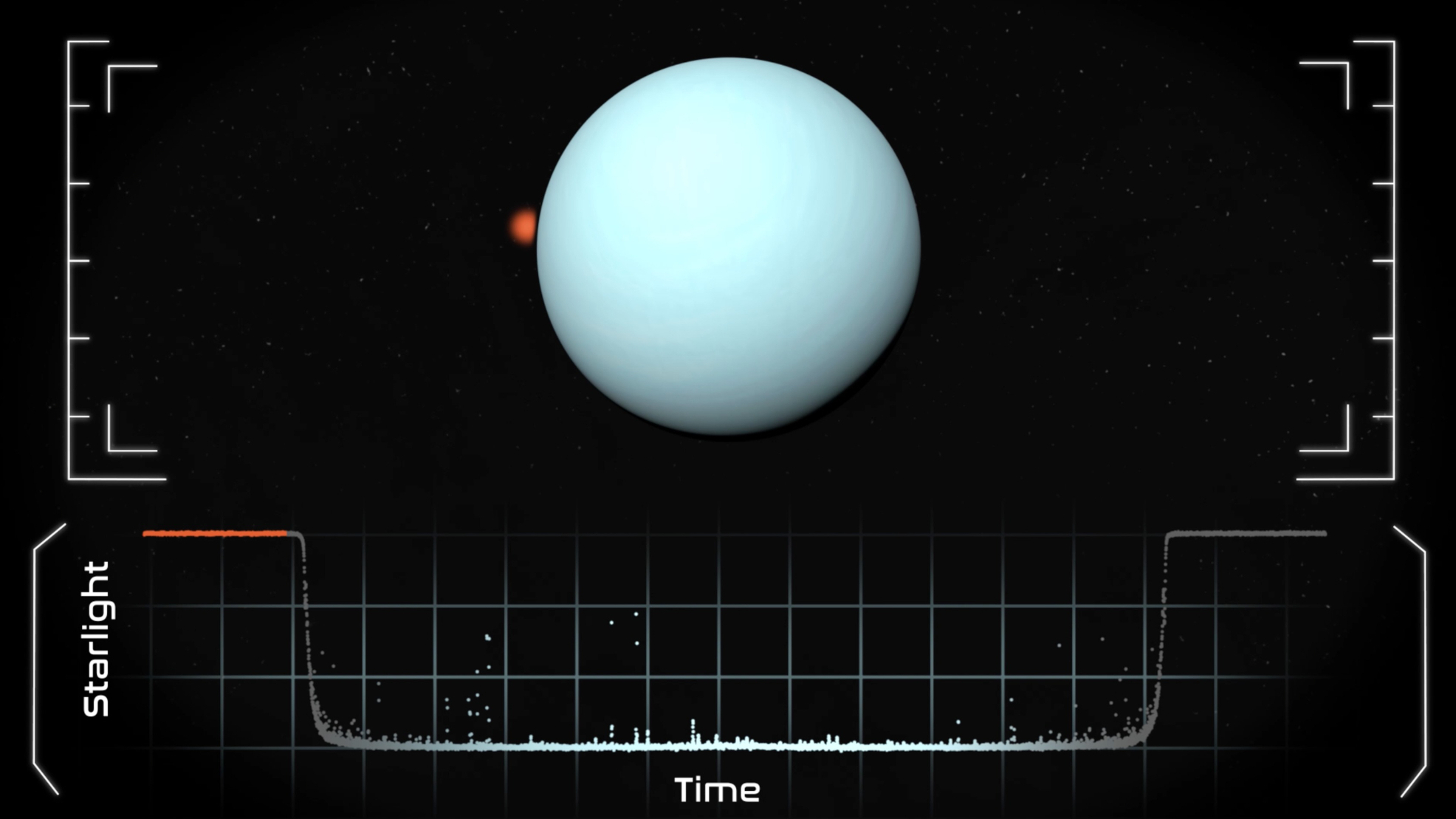

Predawn hours best time to watch

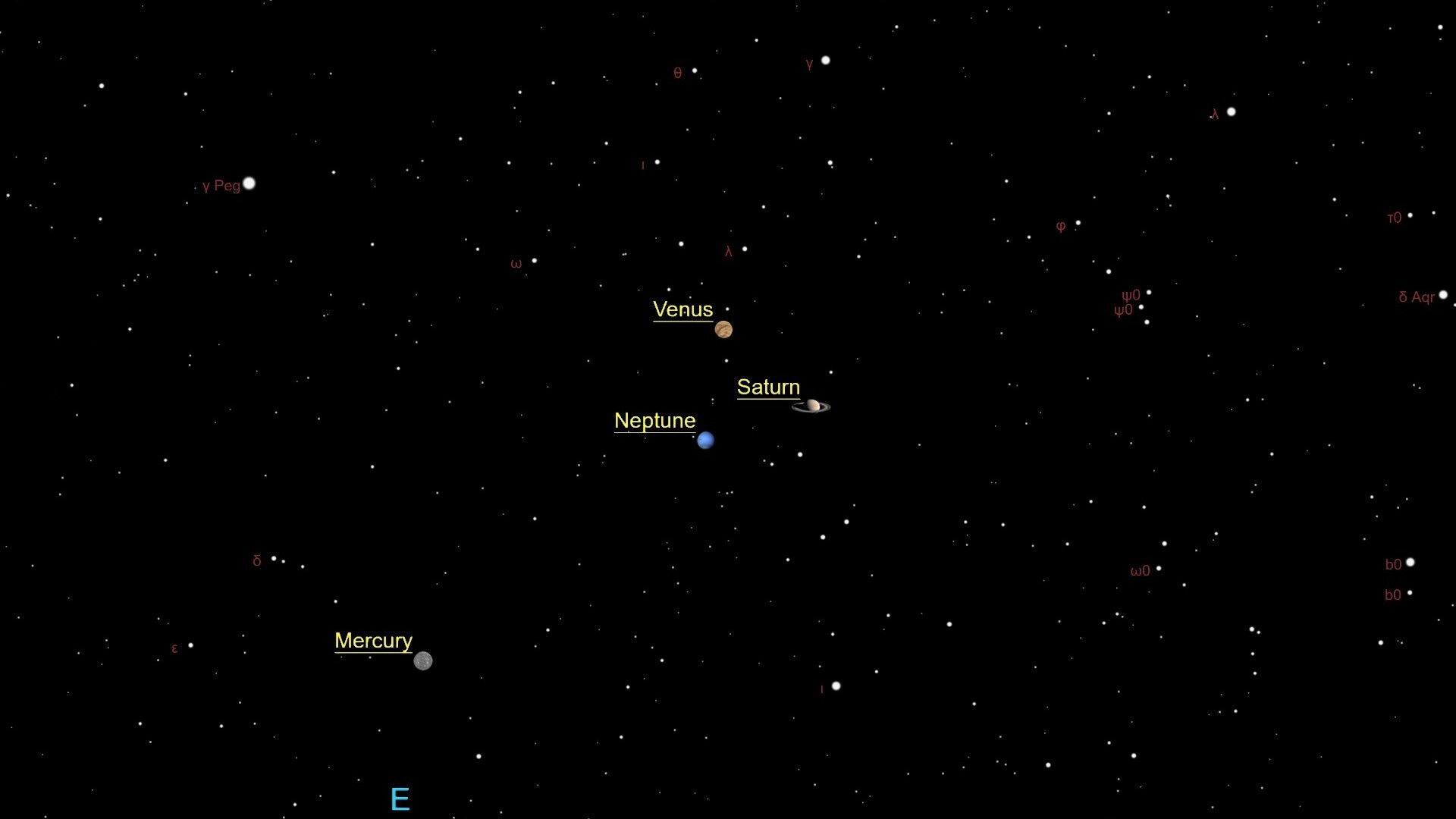

The meteors appear to radiate from around the brilliant star Vega in the constellation of Lyra the Lyre (hence the name "Lyrids"). Any meteor whose path, extended backward, comes within a few degrees of Vega is likely to be a Lyrid. While hardly a rich display — at their peak, one may be expected to average a meteor sighting about every three to five minutes; they're considered to be one of the weaker of the principal displays — Lyrid meteors are categorized as very bright and fairly fast.

You can start watching for them beginning around midnight when Vega will be situated about one-third up in the east-northeast sky. When the first light of dawn is about to break at around 4:30 a.m., Vega has climbed to a position very high — almost overhead — above the eastern horizon.

Bolts out of the blue

The Lyrids are also known for occasional surprises.

There are a number of historic records of meteor displays believed to be Lyrids, notably in 687 B.C. and 15 B.C. in China (where records say "stars fell like rain"), and A.D. 1136 in Korea when "many stars flew from the northeast." On April 20, 1803, many townspeople in Richmond, Virginia, were roused from their beds by a fire alarm and were able to observe a very rich Lyrid display between 1 and 3 o'clock. The meteors "seemed to fall from every point in the heavens in such numbers as to resemble a shower of skyrockets."

That stupendous Lyrid shower of 1803 was completely unexpected, primarily because very little was known about meteors in the 18th and early 19th centuries. But in 1867 Austrian astronomer, Edmund Weiss, and German astronomer, Johann Gottfried Galle made independent calculations that demonstrated that the progenitor of the Lyrid meteors is due to the cosmic dross that was left behind in the wake of Comet Thatcher, which circles the sun in a roughly 415-year orbit and was last seen in the spring of 1861.

More recently, a brief outburst of about 90 per hour was seen in 1922. And then from Japan, 112 meteors (most of them were Lyrids) were seen in 67 minutes on April 22, 1945. Then, in 1982, the hourly rate unexpectedly reached 90 for a single hour and 180 to 300 for a few minutes.

So maybe it wouldn't hurt to set the alarm clock for 3 or 4 a.m. on Tuesday morning, for a brief look out the window. Hey ... you never know.

Normally this shower is above one-quarter peak strength two days before and after maximum, so if the weather in your area is unsettled on the morning of the 22nd, you still have a chance to catch a few Lyrids a day or two before or after the time of their peak activity.

Bonus meteor show?

In addition to the Lyrids, there is also a possibility — albeit quite small — of sighting a brilliant fireball meteor that perhaps is even capable of dropping a meteorite. This declaration is based on two coincidences dating back to the 1960s.

A shadow-casting fireball that passed over northern New Jersey on April 23, 1962, and an exploding meteor (bolide) seen on April 25, 1969 over England, Wales and Northern Ireland and dropped a nearly 10-pound (5 kg) stony meteorite. Both fireballs apparently have much in common.

After orbital computations were made both in the U.S., and Great Britain, it was discovered that these dazzling meteors had remarkably similar orbits and had possibly originated either in the asteroid belt, or as perhaps the debris from an unknown short-period comet. Some astronomers believe that there might be a sparse stream of meteoroids which Earth might encounter during the final week of April. Some of these chunks of stone just might give rise to associated fireballs and perhaps even meteorite falls.

Both the 1962 and 1969 fireballs emanated from a part of the sky near the constellation Corvus the Crow, which is composed of four moderately bright stars in the shape of a quadrilateral. Corvus can be found at nightfall about one-quarter up in the south-southeast part of the sky. It crosses the meridian shortly after 11 p.m. local daylight time and sets in the west-southwest around 4 a.m.

So, if you're out and about during the overnight hours of April 23-24 and/or 24-25, be vigilant. If you're very lucky and nature is in a show-off mood, you just might catch sight of an outstandingly bright meteor blazing a south-to-north path across the night sky.

Want to try and capture the Lyrids on camera? See our guides on how to photograph meteors and meteor showers the best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky and Telescope and other publications.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.