Starshade exoplanet-hunting missions may be technologically daunting, but they're not beyond NASA's reach, recent research suggests.

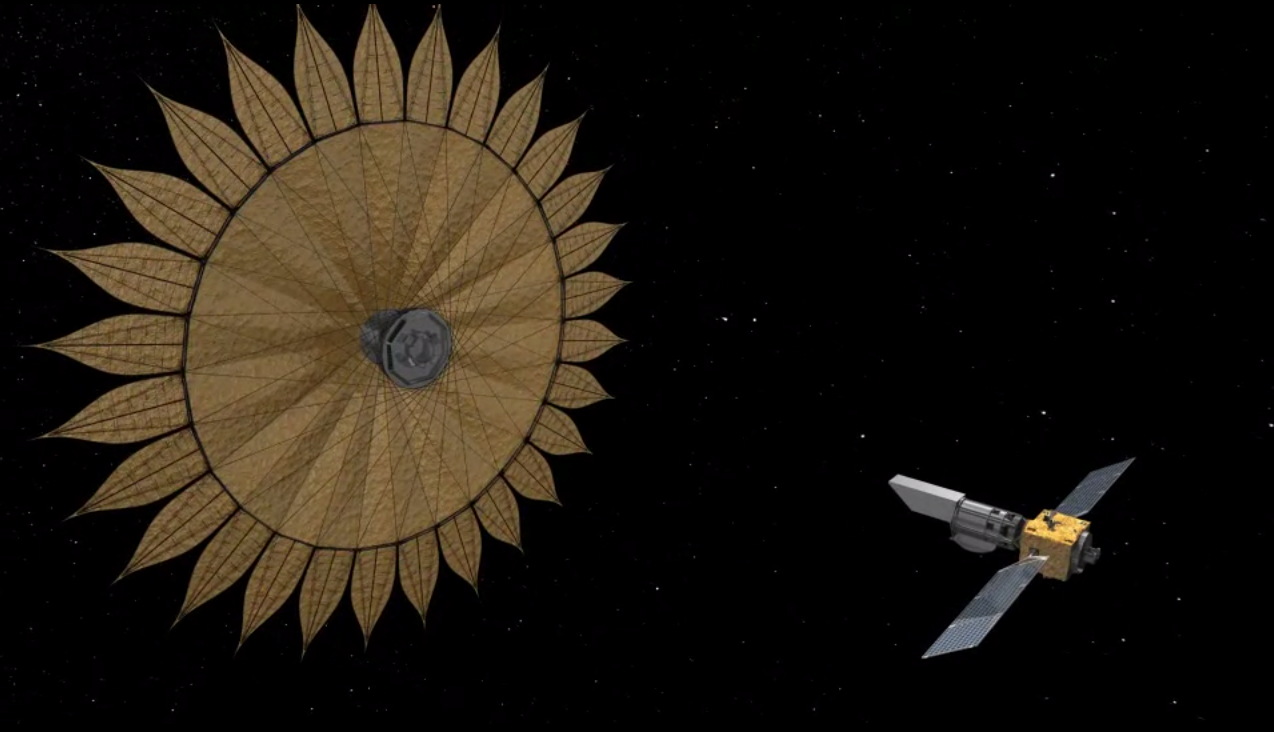

Such a mission would employ a space telescope and a separate craft flying about 25,000 miles (40,000 kilometers) ahead of it. This latter probe would be equipped with a large, flat, petaled shade designed to block starlight, potentially allowing the telescope to directly image orbiting alien worlds as small as Earth that would otherwise be lost in the glare.

(Instruments called coronagraphs, which have been installed on multiple ground-based and space telescopes, work on the same light-blocking principle. But coronagraphs are incorporated into the telescope itself.)

RELATED: The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)

There are no starshade missions on NASA's books as of yet. For such a project to work, the two spacecraft would need to be aligned incredibly precisely — to within about 3 feet (1 meter) of each other, NASA officials said.

"The distances we're talking about for the starshade technology are kind of hard to imagine," Michael Bottom, an engineer at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California, said in a statement.

"If the starshade were scaled down to the size of a drink coaster, the telescope would be the size of a pencil eraser, and they'd be separated by about 60 miles [100 kilometers]," Bottom added. "Now imagine those two objects are free-floating in space. They're both experiencing these little tugs and nudges from gravity and other forces, and over that distance we're trying to keep them both precisely aligned to within about 2 millimeters."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Slight alignment failures could theoretically be detected by a camera inside the space telescope. Small amounts of starlight will always leak around the starshade, forming a light-and-dark pattern on the scope. The camera would pick up misalignments by recognizing when the light-and-dark pattern was off-center.

Bottom devised a computer program that tested whether this technique could actually work — and the results were encouraging.

"We can sense a change in the position of the starshade down to an inch, even over these huge distances," Bottom said in the same statement.

Meanwhile, fellow JPL engineer Thibault Flinois and his colleagues came up with their own suite of algorithms, which use information from Bottom's program to determine when the starshade should autonomously fire its thrusters to maintain alignment.

Put together, this work — which is detailed in a report completed earlier this year — suggests that starshade missions are technologically feasible. Indeed, it should be possible to keep a big starshade and a space telescope aligned at distances up to 46,000 miles (74,000 km), NASA officials said.

"This to me is a fine example of how space technology becomes ever more extraordinary by building upon its prior successes," Phil Willems, manager of NASA's Starshade Technology Development activity, said in the same statement.

"We use formation flying in space every time a capsule docks at the International Space Station," Willems added. "But Michael and Thibault have gone far beyond that and shown a way to maintain formation over scales larger than Earth itself."

- 7 Ways to Discover Alien Planets

- 10 Exoplanets That Could Host Alien Life

- Incredible Technology: Space Tech on the Horizon

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.