Scientists reveal secrets about elusive mid-sized black holes

A new computer model is uncovering new the clues.

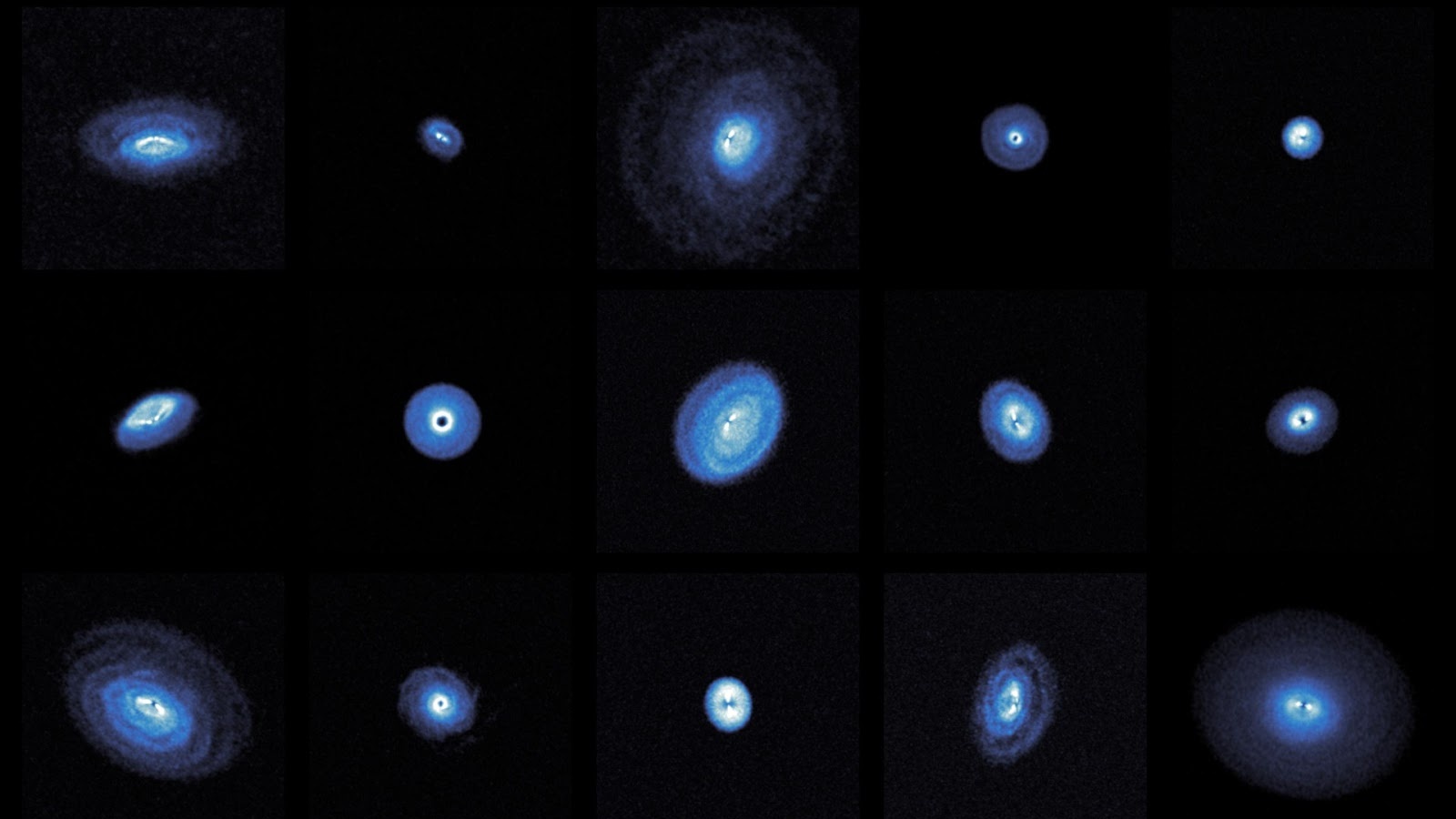

Scientists are uncovering how mysterious medium-sized black holes may arise from collisions of massive stars.

Until recently, there have been just two types of black holes: stellar black holes, which are 10 to 100 times the mass of our sun, and supermassive black holes, which are millions or more times larger and lurk at the heart of galaxies like the Milky Way.

In 2019, however, significant evidence for what's called an intermediate-mass, or mid-sized, black hole arose.

The gravitational wave detectors LIGO (the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory) and Virgo detected the gravitational wave GW190521, which was so powerful that it must have been triggered by a collision that gave rise to a black hole much larger than the upper limit for stellar black holes. However, at the same time, the object was nowhere near enough massive to be a galactic supermassive black hole.

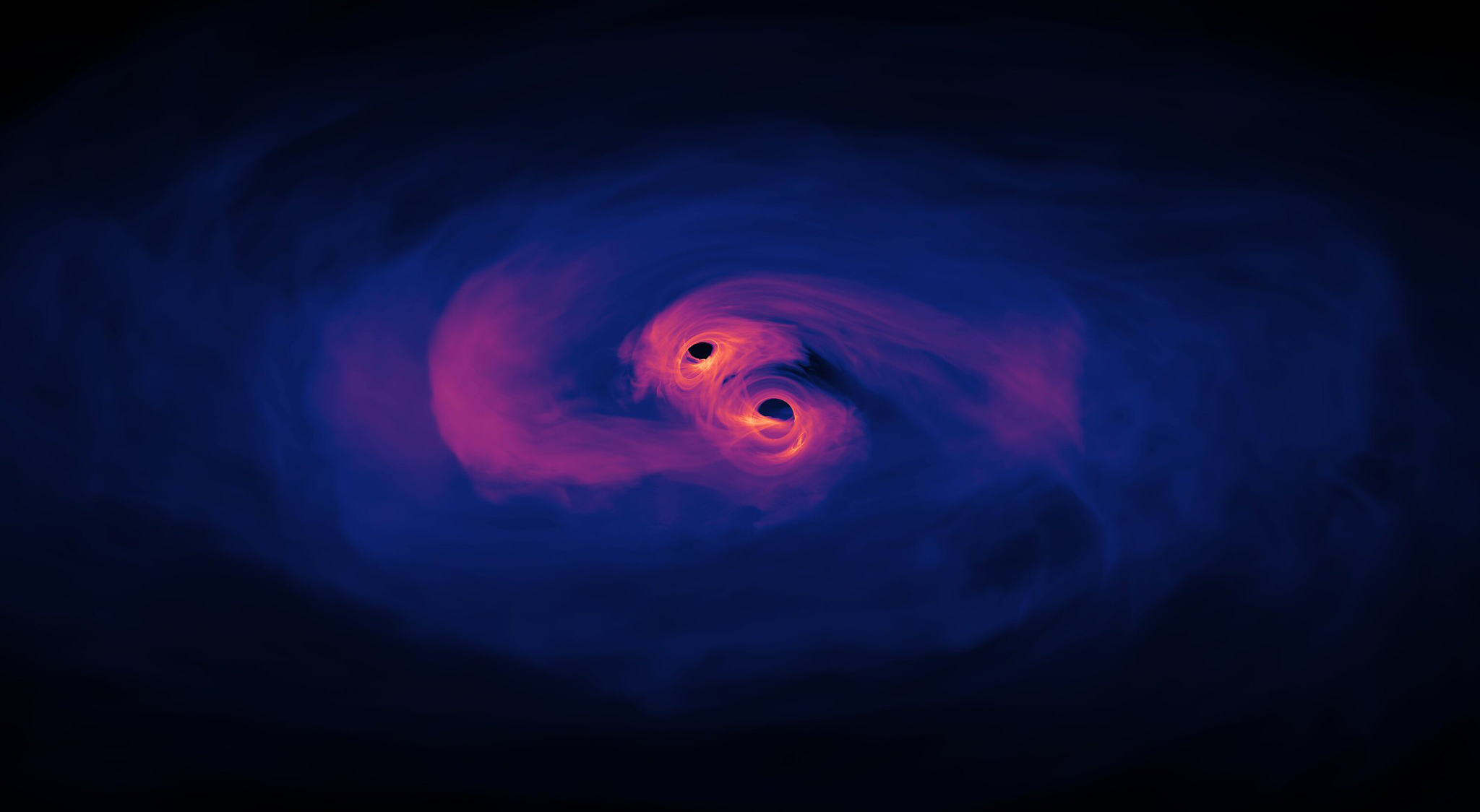

Related: Watch two monster black holes merge into one in this intricate NASA simulation (video)

Even before the detection of GW190521, astrophysicists hypothesized that such mid-sized black holes must exist, as they would provide the missing link between the two observed varieties.

When researchers modeled the birth of GW190521, they found that it must have been triggered by a collision between two progenitor black holes, one as massive as 85 suns and one somewhat smaller with 66 solar masses. The resulting black hole would have a mass of 140 suns, which falls within the previously unseen intermediate category.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A new study now suggest that that medium-sized black hole could also have been born from a collision of two giant stars

According to astrophysicist Michela Mapelli, an astrophysicist at the University of Padova in Italy and leader of the new research, no one has simulated collisions of such massive stars before.

Mapelli leads a research project called DEMOBLACK, which uses computer simulations to model how black holes emerge and merge inside clusters of stars. And the new study came out of this work.

The team in this new study began its simulation with two stars: one very young hydrogen-burning star about 40 times as massive as the sun and one older star with a mass of about 60 suns. The older star is in the later, red giant stage of its evolution, when stars burn helium in their core and balloon to sizes hundreds of times greater than their original size.

Scientists know that stellar black holes are born when old stars collapse at the end of their lives. But due to physics constraints, these black holes can be only 65 times as heavy as the sun at the most, according to LIGO. That obviously means that both of the progenitor black holes, which scientists believe gave rise to GW190521, already had to be products of earlier mergers or have eaten up a lot of matter since their birth.

Models suggest that stellar black holes can form so-called binary systems, when they orbit each other while gradually getting closer and closer. Eventually, they merge. Repeated collisions and mergers could produce black holes of much higher masses, of up to 10,000 times the mass of the sun, Mapelli said.

Some theorists believe that medium-sized black holes somehow formed in the early universe shortly after the Big Bang as the so-called primordial black holes. Alternatively, black holes are believed to grow by devouring surrounding matter, but that fails to explain the sheer sizes of those that lurk inside galaxies.

Scientists hope that discovering more medium-sized black holes will help them crack those mysteries in the future.

The new study was presented on Monday (April 11) at the April meeting of the American Physical Society.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter at @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.