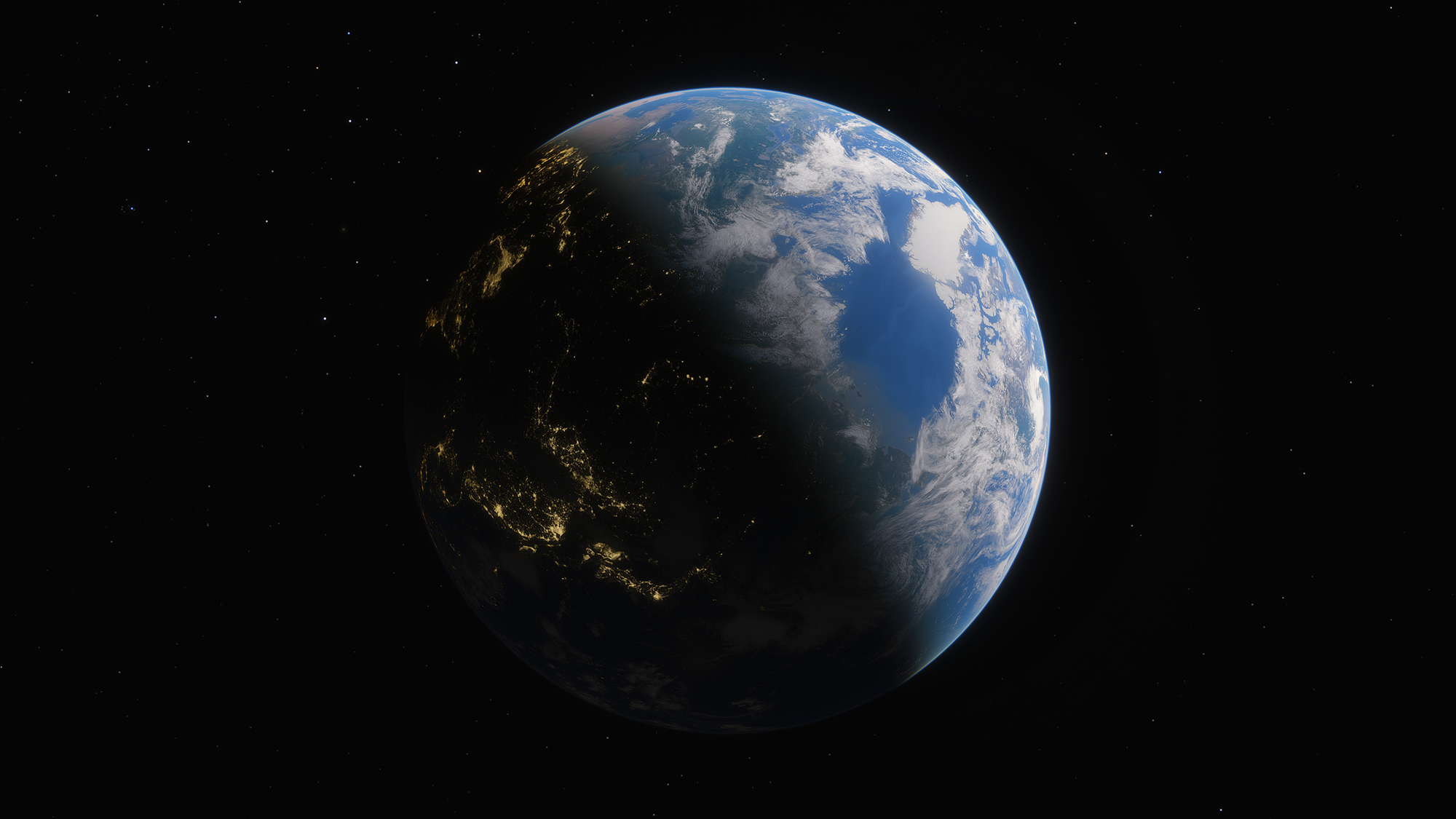

Summer will arrive in the Northern Hemisphere on Saturday (June 20) at 5:43:32 p.m. EDT (21:43:32 GMT). The June solstice also marks the beginning of winter for those in the Southern Hemisphere.

It will be a celestial event that will likely get a good deal less attention than April's so-called "supermoon," the biggest full moon of the year. After all, you can see the moon, but the solstice is merely a calculation. You can't even see the change in the span of daylight, which, for those living at mid-northern latitudes is virtually the same on June 20 as the day before and will have diminished by only half an hour by July 23. In short, summer doesn't arrive with banners and fanfare, and for some places summer heat has already been well established since early May.

At the moment of the solstice, the sun will appear to be shining directly overhead for a point on the Tropic of Cancer (latitude 23.5 degrees north) in the central Pacific Ocean, 817 miles (1,314 kilometers) east-northeast from Honolulu. With the prime exception of Hawaii, we can never see the sun directly overhead from the other 49 U.S. states, but on Saturday, at around 1 p.m. local daylight time, the sun will attain its highest point in the sky for this entire year.

Related: Stunning summer solstice photos (gallery)

Since the sun will appear to describe such a high arc across the sky, the duration of daylight in the Northern Hemisphere is now at its most extreme, in most cases lasting over 15 hours. However, contrary to popular belief, the earliest sunrise and latest sunset do not coincide with the summer solstice. The earliest sunrise actually occurred back on June 14, while the latest sunset is not due until June 27. Dawn breaks early; dusk lingers late.

The hottest days are yet to come

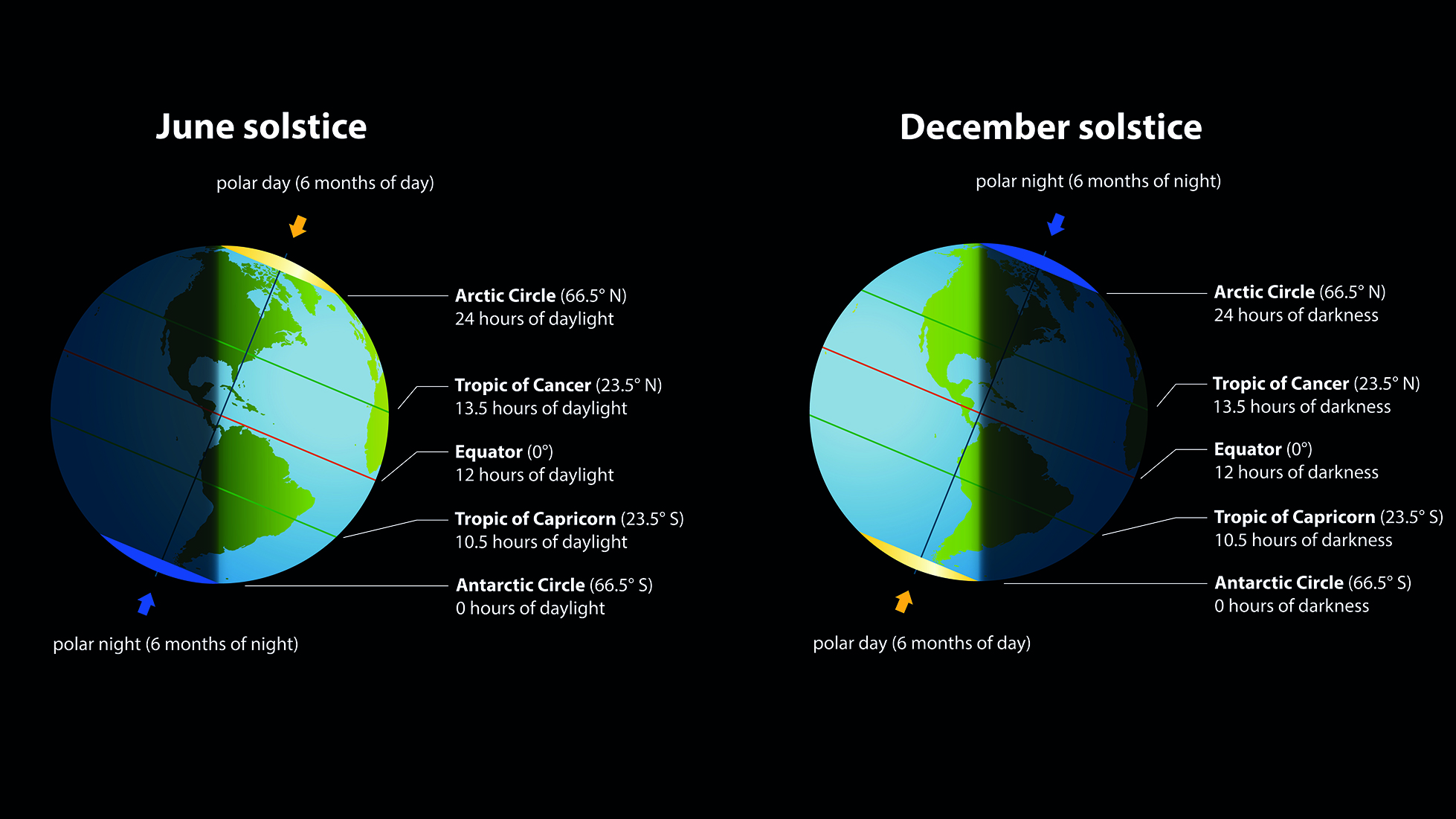

As astronomy books explain, the plane of the Earth's equator is tilted 23.5 degrees to our orbit around the sun. During the year varying amounts of sunlight strike different regions of the planet. Both the angle of incidence of the radiation and the length of daylight change significantly.

The total energy we receive from the sun is called "insolation," and were that the only factor that regulated our temperatures, then right now the Northern Hemisphere would be experiencing the hottest weather of the year. But it doesn't work that way because our atmosphere in the temperate regions continues to receive more heat than it gives up to space, a situation that lasts a month or more, depending on the latitude.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If we were to check long-term weather records for, as an example, in New York's Central Park, we would find that the hottest stretch of average temperatures run from July 8 through Aug. 9; 3.5 to more than 7 weeks after the solstice.

And a reverse process occurs after the winter solstice in December. The solar heating depends directly on the sun's altitude in the sky, which also controls its daily path and the number of hours the sun is above the horizon.

On April 12, the sun takes the same path across the sky as on Aug. 31. But because of the seasonal lag, New Yorkers have seen a couple of inches of snow (in 1918) or a temperature as low as 25 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 4 degrees Celsius) in 1976 on the first date and sweltered through 100 degrees F (38 degrees C) on the other day, as happened in 1953.

For far northern climes, it's "mid-summer"

In the more northerly parts of the world, the solstice is looked upon not as the start of summer, but rather as mid-summer. If, for example, you were to visit Norway or Sweden at this time of year, you would find the local inhabitants making merry in celebration of Midsummer's Day, which by ancient custom is June 24, a day also linked with the name of St. John the Baptist. At night, fires are lighted in the mountains in other parts of Europe.

In northern Scandinavia, above the Arctic Circle, the phenomenon of the midnight sun at solstice time is a seasonal clock which seems to divide summer — if not the whole year — into two distinct parts. It's looked upon as the annual period of climax, when the conquering sun scores its grandest victory over the forces of darkness. If you look at things from this perspective, you come to realize that it's hard to regard such a time as the beginning of a season which to all appearances has actually reached its height.

North of latitude 55 degrees, since the start of May, a twilight glow has persisted through the night; dim at first, but now at the solstice it appears quite bright. And it will persist all the way through July before finally fading out completely in early August; such subarctic twilights virtually abolish night.

Even places well outside of the Arctic Circle, the sun goes below the horizon for only 8 or 9 hours. From Philadelphia, Chicago and Denver, taking twilight into account, there are only about five hours of total darkness.

Now for something a little different

If the plane of the Earth's equator were not tilted 23.5 degrees, but was oriented straight up and down, we would not have seasons. Every day around the globe would be 12 hours long, and each day the sun would appear to describe the same path across the sky. But thanks to the tilt of the Earth's axis, the sun describes a slightly different path across our sky and the duration of daylight changes slightly with each passing day.

On many world globes, you might have noticed in the eastern Pacific Ocean an unusual looking plot or graph in the shape of a figure eight or a bowling pin. This is called an analemma and its purpose is to depict the position of the sun in the sky, as seen from a fixed location on Earth at the same mean solar time, as that position varies over the course of a year.

The bottom of the "8" appears wider than the top, because at the bottom (close to the time of the winter solstice) the Earth, moving in its elliptical orbit around the sun, is also closest to the sun in its orbit. It therefore is moving fastest and appears to take a wide, sweeping turn at the bottom of the analemma plot. Conversely, when the sun appears at its most northerly position in the sky (the summer solstice), we find it positioned near the top of the "8." And because the Earth is also nearing its farthest point from the sun (called "aphelion") and moving slowest in its orbit during early July, the upper loop appears decidedly smaller.

So thanks to Earth's axial tilt and our elliptical orbit, the sun's daily position for a specific time of the day, plotted over the course of the year, describes this lopsided figure eight in the sky.

And if you've ever watched the 2000 movie "Castaway," perhaps you noticed that Chuck Nolan, played by Tom Hanks, who was stranded on a remote island, constructed an analemma on the wall of a cave and utilized it as a calendar — thus he knew when the trade winds changed directions in order to make his escape. Robert Zemeckis, who directed and co-produced this film, is to be commended in having Nolan's analemma oriented upside-down (since his island was in the Southern Hemisphere). However, the one hitch to this whole concept is that in order for an analemma to work properly, you need to periodically check it against an accurate timepiece, and unfortunately, the pocket watch that Nolan's girlfriend (Kelly) gave him, stopped working after it became drenched with sea water.

Oh well ... that's Hollywood.

A final thought

Be advised that one minute after the solstice arrives, the sun will have already begun its annual southward migration, and the length of daylight will begin to get shorter. It will be imperceptible at first, but once we cross over into August most everyone will start to notice that the early mornings are not so bright, and that evening darkness is coming decidedly earlier.

The days won't begin to lengthen again until three days before Christmas. As American author, journalist and naturalist, Hal Borland once wrote: "Summer is a promissory note signed in June, its long days spent and gone before you know it, and due to be repaid next January."

But summer is here now. So make it a good one!

- Infinite loop: see the sun's yearlong figure-eight in the sky (photo)

- Why the night sky changes with the seasons

- What if winter lasted for years like it does on 'Game of Thrones'?

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

-

Wolfshadw Days start getting shorter as we in the Northern Hemisphere begin our slow, inexorable crawl towards Winter!Reply

-Wolf sends