Equinox increases chances of geomagnetic storm from solar eruption this week

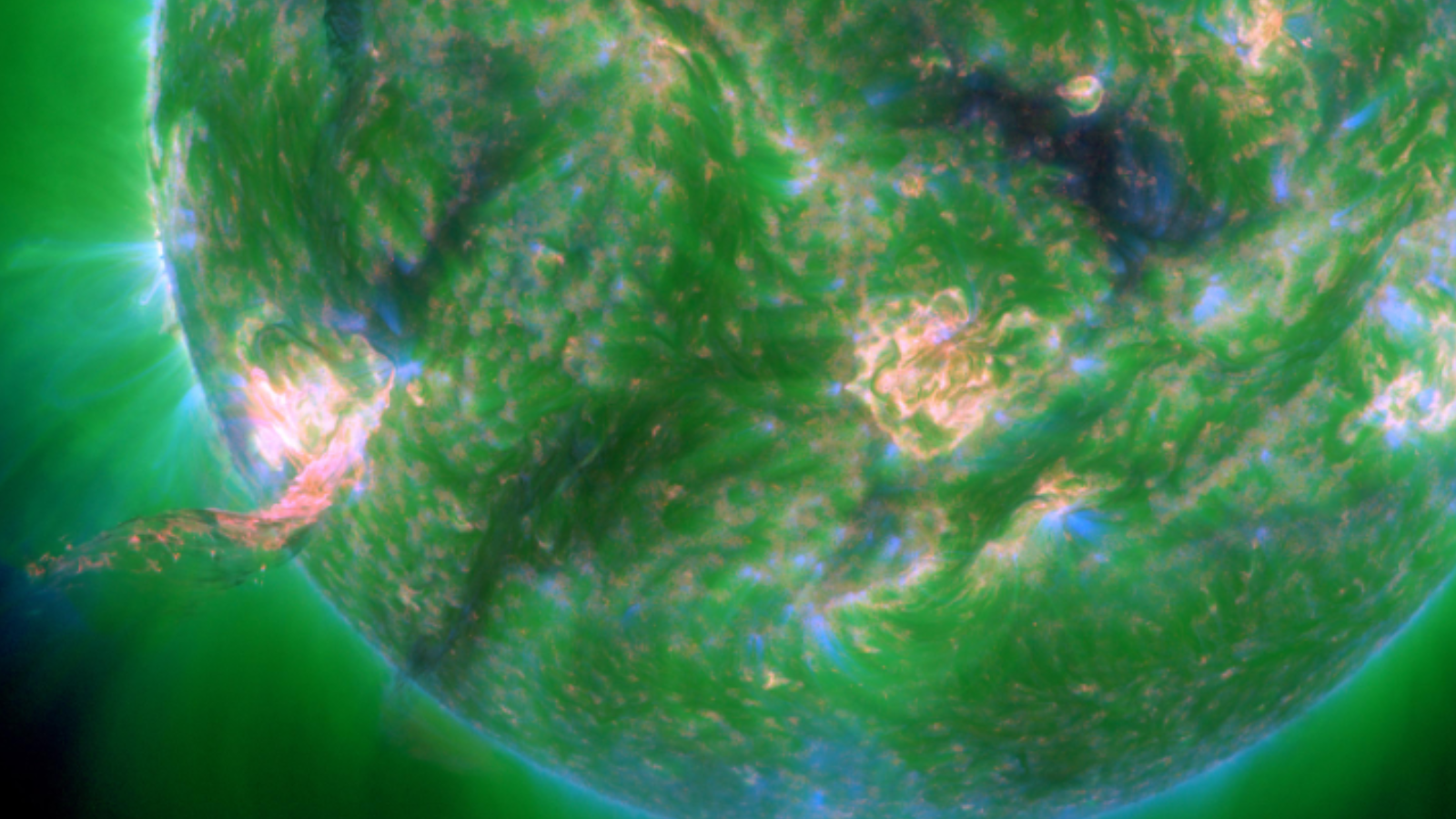

The sunspot AR3835 erupted on Sunday (Sept. 22) during Earth's equinox when a glancing blow can cause a geomagnetic storm.

Earth could experience a geomagnetic storm on Wednesday (Sept. 25) after the sun lashed out with a huge spout of plasma. The probability of our planet experiencing effects from the geomagnetic storm may be higher due to the fact that this particular solar outburst occurred around the same time as Earth's autumnal equinox.

The coronal mass ejection (CME) was unleashed on Sunday (Sept. 22) at 5:39 p.m. EDT (2139 UTC) when a sunspot designated AR3835 erupted unexpectedly with an M-class solar flare. Solar scientists weren't expecting this eruption because AR3835 had seemed too stable to explode, according to SpaceWeather.com.

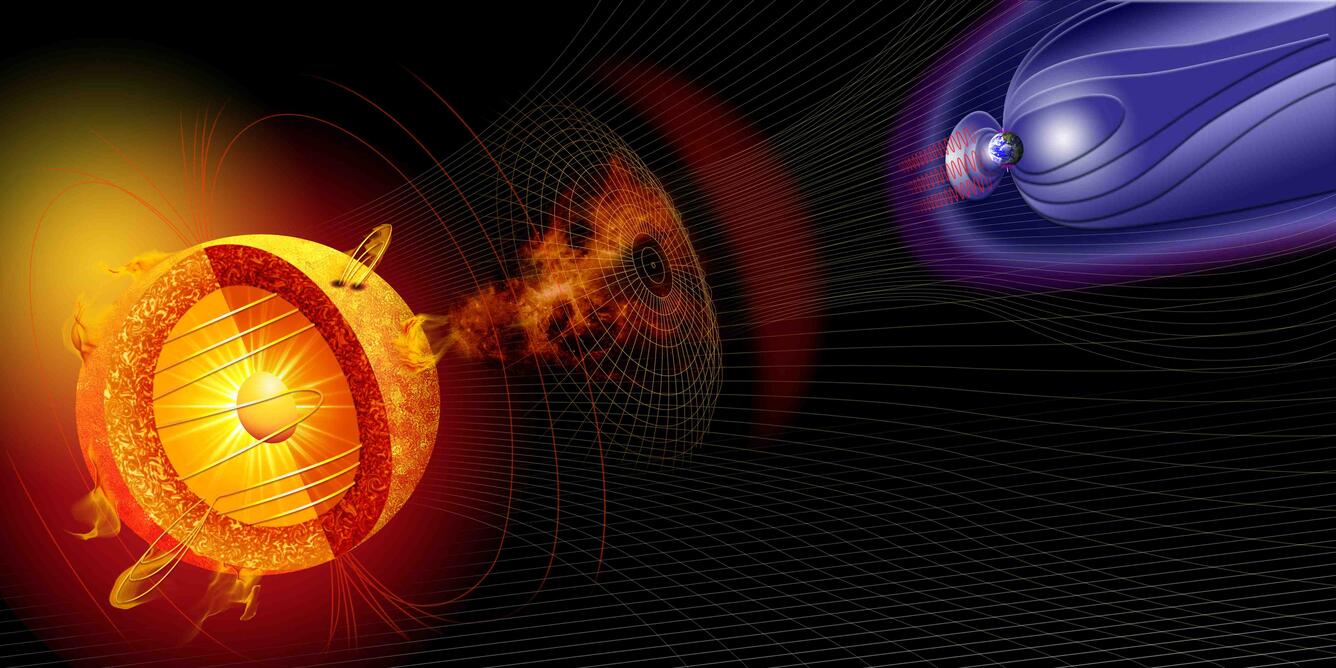

Currently rocketing toward Earth at over 650,000 miles per hour (1,046,073 kilometers per hour), this tendril of solar plasma will only strike a glancing blow on Earth's protective magnetic bubble, the magnetosphere, with the majority missing Earth, according to NASA modeling. This normally wouldn't trigger a geomagnetic storm, but that might be different on Wednesday because of the timing of this CME.

When geomagnetic storms do strike, they can disrupt communication and power infrastructure and, in extreme cases, blackouts. At high altitudes, geomagnetic storms can also result in stunning displays of light called auroras.

The NOAA Space Weather Prediction Center ranks geomagnetic storms on a scale of G1 to G5. These storms rise in severity, with G5-scale geomagnetic storms being the most extreme events capable of causing complete collapse or blackouts of power and communicatons systems. A G1 or G2 storm, such as that which could potentially occur on Wednesday, has a slight risk of impacting infrastructure at high latitudes.

Related: Sun fires off X-class solar flare, increasing aurora viewing chances into weekend

Equinoxes occur when Earth's rotational axis aligns with its orbit around the sun. During the equinoxes, Earth does not appear to tilt with respect to the sun. This means the sun sits directly above the equator and both hemispheres get the same hours of daylight and night.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The autumnal equinox 2024 occurred at 8:44 a.m. EDT (1244 GMT) on Sunday, marking the first day of Autumn for the northern hemisphere and the first day of Spring for the southern hemisphere.

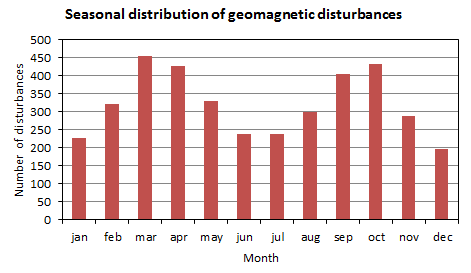

The weeks around Earth's two equinoxes mark an increase in geomagnetic storm frequency.

This is probably due to the fact that as Earth orientates its poles to point at the sun, the magnetosphere and the sun's magnetic field become aligned, whereas they tend to be misaligned throughout the rest of the year. At times of misalignment, charged particles from the sun, such as CMEs and solar winds, receive a slight deflection from the magnetosphere, meaning we avoid their full impacts.

This deflection doesn't occur during periods around the equinoxes when the magnetic fields of our planet and our star are well connected. This is called the "Russell-McPherron effect," and it was first suggested in 1973 to explain the seasonal variation in geomagnetic storm frequency.

Similarly, Earth experiences the least geomagnetic storms around the months of the solstices, December and January, and again during June and July, when Earth's pole are pointed towards the sun. Data collected from 1932 to 2014 has shown geomagnetic storms are, on average, about twice as likely around the times of the equinoxes as they are around the time of the solstices.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.