Sun's gravitational lens could help find life on exoplanets

The sun's gravity could act like a giant magnifying glass to help view distant exoplanets in amazing detail.

The sun's gravitational field could be used as a giant magnifying glass to observe distant exoplanets in a much greater detail than is currently possible, a new study suggests.

In the study, a team of researchers from Stanford University proposed a technique for studying exoplanets that uses gravitational lensing, an effect that occurs around massive celestial bodies where the gravity of the objects is strong enough to bend spacetime. An object viewed through this bent region of spacetime appears closer and larger, as if observed through a magnifying lens. Combining the power of space-based telescopes with gravitational lensing could improve the precision of imaging of exoplanets, planets that orbit other stars, 1,000 times, the researchers said in a statement.

"We want to take pictures of planets that are orbiting other stars that are as good as the pictures we can make of planets in our own solar system," Bruce Macintosh, a physics professor at the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford and deputy director of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology (KIPAC) said in the statement. "With this technology, we hope to take a picture of a planet 100 light-years away that has the same impact as Apollo 8's picture of Earth."

Related: Einstein's gravitational lenses could clear up roiling debate on expanding cosmos

So far, however, the technique described in this study only works in theory. For a telescope to be able to use gravitational lensing with the sun, it would have to be placed 14 times farther away from the sun than the dwarf planet Pluto, the scientists said in the statement. No human-built spacecraft has ever ventured that far.

Since even the nearest exoplanets are tens of light-years away, it would take an extremely large telescope to see them in detail without gravitational lensing. The scientists estimate that a telescope would have to be 20 times wider than Earth to view those worlds in detail, the researchers said.

With gravitational lensing, the team thinks that they would be able to see surface structures on these planets with observatories the size of the Hubble Space Telescope.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The solar gravitational lens opens up an entirely new window for observation," Alexander Madurowicz, a PhD student at KIPAC and lead author of the study, said in the statement. "This will allow investigation of the detailed dynamics of the planets' atmospheres, as well as the distributions of clouds and surface features, which we have no way to investigate now."

Once they can see such minute details, astronomers would be able to easily determine whether life could exist on any of these distant worlds.

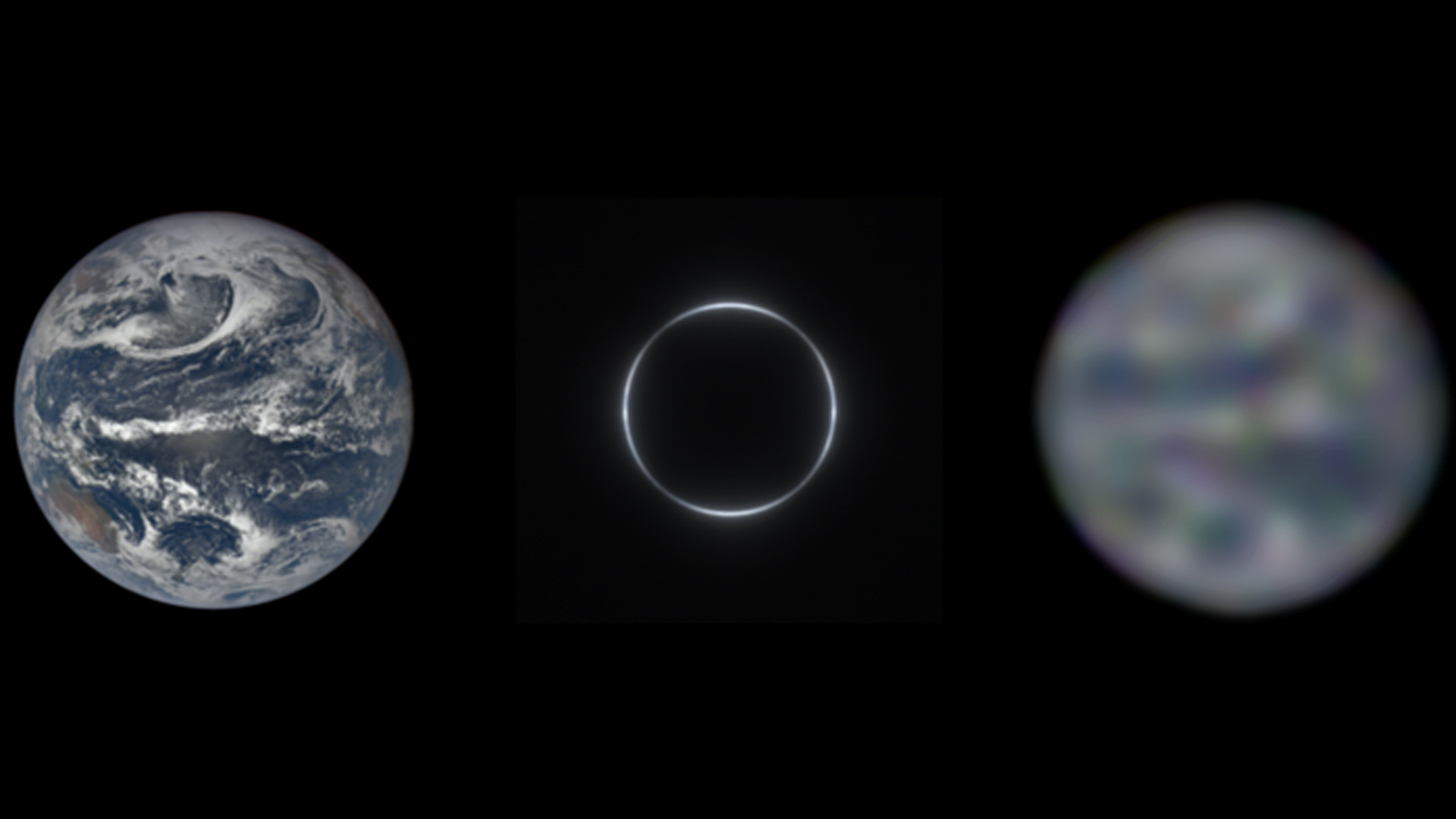

The gravitational lensing method described in this study would enable astronomers to reconstruct the image of a planet's surface from a single picture taken looking directly at the sun, according to the researchers. With this newly-described technique, a telescope's view of an exoplanet would create a "ring of light" in the sun's gravitational lens. A special algorithm designed by the Stanford University team could then undistort the light by "reversing the bending from the gravitational lens, which turns the ring back into a round planet," the researchers said in the statement.

"By unbending the light bent by the sun, an image can be created far beyond that of an ordinary telescope," Madurowicz said. "So, the scientific potential is an untapped mystery because it's opening this new observing capability that doesn't yet exist."

The work was inspired by an earlier paper by scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California. This paper proposed a space-based telescope that would use rockets to scan around the rays of light from a planet to reconstruct a clear picture. The technique, however, would require a lot of fuel and time, the researchers said.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.