Sun breaks out with record number of sunspots, sparking solar storm concerns

The sun hasn't produced this many sunspots in a single month since 2002.

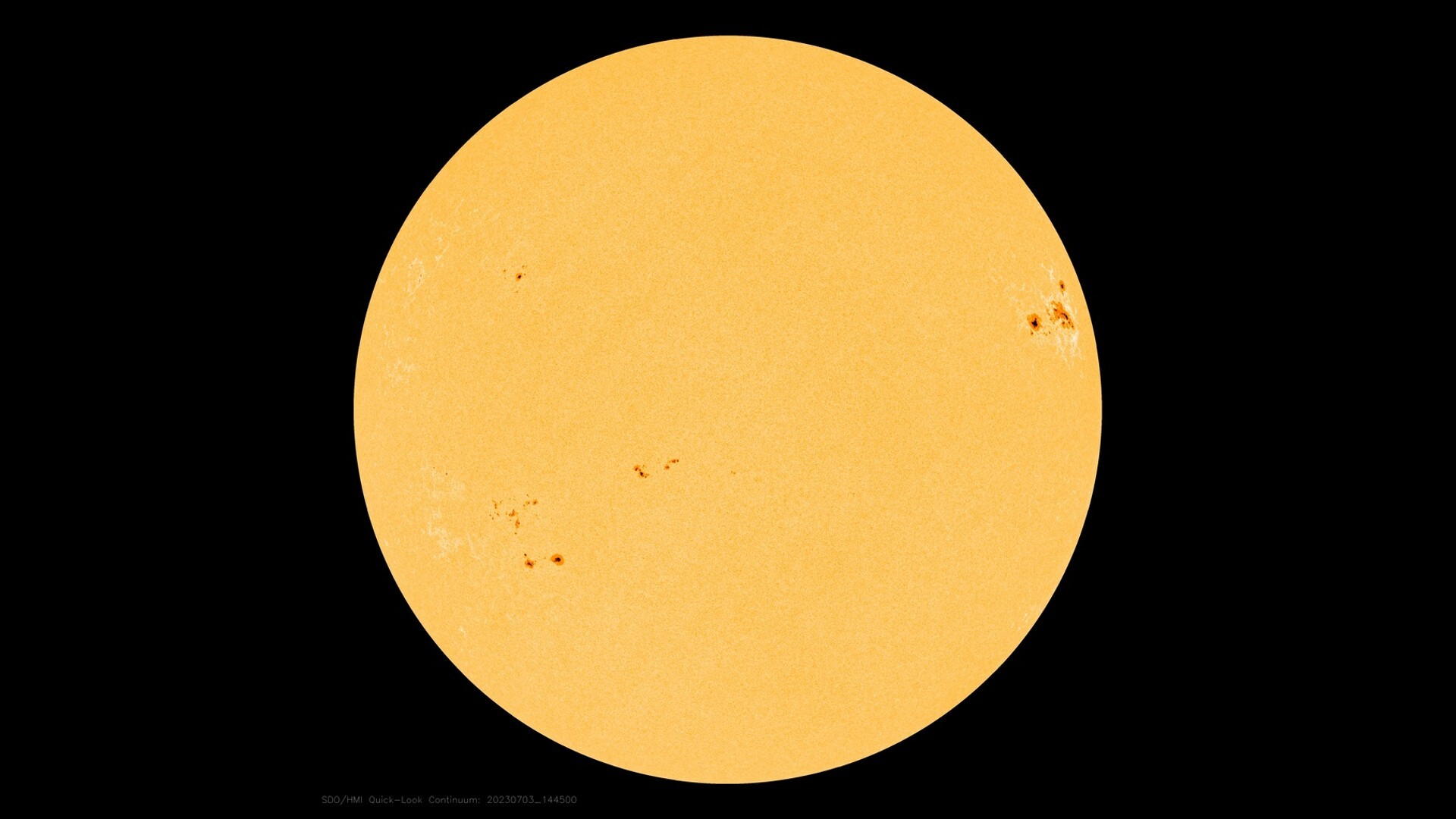

The sun produced over 160 sunspots in June, the highest monthly number in more than two decades.

The data confirm that the current solar cycle, the 25th since records began, is picking up intensity at a much quicker pace than NASA and the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasted, sparking concerns of severe space weather events in the months and years to come.

While the space agencies predicted a maximum monthly number of sunspots during the 25th solar cycle's maximum to reach a modest 125, the star is now on a trajectory to peak at just under 200 monthly sunspots, and some scientists think this peak may arrive in just one year.

"Highest monthly average sunspot number since September 2002!" solar physicist Keith Strong shared on Twitter on Sunday. "The June 2023 [sunspot number] was 163.4, the highest value for over 20 years."

Related: NASA mission to 'ignorosphere' could improve space weather forecasts

HIGHEST MONTHLY AVERAGED SUNSPOT NUMBER SINCE SEPTEMBER 2002! The June 2023 SNN was 163.4 the highest value for over 20 years. The CM model is now forecasting a peak for SC25 of just under 200, the CM model at 125 (SC42 was 116). Any Grand Solar Minimum believers left out there? pic.twitter.com/uw0JCeooe1July 1, 2023

On Sunday (July 2), one of these sunspots, the darker, cooler areas on the star's surface that feature dense, strong magnetic fields, produced a powerful solar flare, an energetic flash of light, that caused a temporary radio blackout in the western U.S. and over the Pacific Ocean, according to Spaceweather.com. Such events might become more common in the near future as the solar cycle approaches its maximum.

And contrary to the original NASA and NOAA forecast, this maximum might get rather fiery. More sunspots means not only more solar flares but also more coronal mass ejections, powerful eruptions of charged particles that make up solar wind. And that can mean bad space weather on Earth. Intense bursts of solar wind can penetrate Earth's magnetic field and supercharge particle's in Earth's atmosphere, which triggers mesmerizing aurora displays but also causes serious problems to power grids and satellites in Earth's orbit.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tom Berger, a solar physicist and director of the Space Weather Technology Center at the University of Colorado, Boulder, told Space.com in an earlier interview that after a major solar storm that hit Earth in October 2003, satellite operators lost track of hundreds of spacecraft for several days. This happened due to the increase in gas density in the highest layers of the atmosphere that correspond with the low Earth orbit region where many satellites, as well as the International Space Station, reside.

As the otherwise thin gas in this region interacts with the solar wind, the atmosphere swells up, causing satellites to suddenly face much more drag, or resistance, than they do in calm space weather.

"In the largest storms, the errors in the orbital trajectories become so large that, essentially, the catalog of orbital objects is invalidated," Berger told Space.com. "The objects can be tens of kilometers away from the positions last located by radar. They are essentially lost, and the only solution is to find them again with radar."

Experts worry that due to the growth in the number of satellites and space debris fragments that the low Earth orbit experienced since the last serious solar storm, such a situation might result in orbital chaos that could last for weeks. During this period, the risk of dangerous collisions with space debris fragments would be exceptionally high, creating further risk to satellite operators.

Various operators have already experienced early space weather trouble, including SpaceX, which lost a batch of 40 new Starlink satellites after launching them into what they thought was just a mild solar storm. The mishap that took place in February 2022 saw the brand new spacecraft burn-up in Earth's atmosphere when they couldn't raise their orbits after launch due to the unexpected drag. The European Space Agency (ESA) also reported problems last year after its three Swarm satellites, which study the planet's magnetic field, started losing altitude at a rate never seen before. Operators had to use the spacecrafts' thrusters to prevent them from falling to Earth in the denser gas.

During extreme events, charged solar particles can even damage spacecraft electronics, disrupt GPS signals and knock out power grids on Earth. During the most intense solar storm in history, the Carrington Event of 1859, telegraph clerks reported sparks flying off their machines, setting documents ablaze. The disruption to telegraph services in Europe and North America lasted for several days.

NASA solar physics research scientist Robert Leamon told Space.com in an earlier interview that the worst solar storms tend to arrive during the declining phase of odd solar cycles. Some challenging years might therefore lie ahead for spacecraft operators.

"Since Cycle 25 is odd, we might expect the most effective events to happen after the maximum, in 2025 and 2026," Leamon said. "This is because how the poles of the sun flip every 11 years. You want the pole of the sun in the same orientation compared to the poles of Earth so that then causes the most damage and the best coupling from the solar wind through Earth's magnetic field."

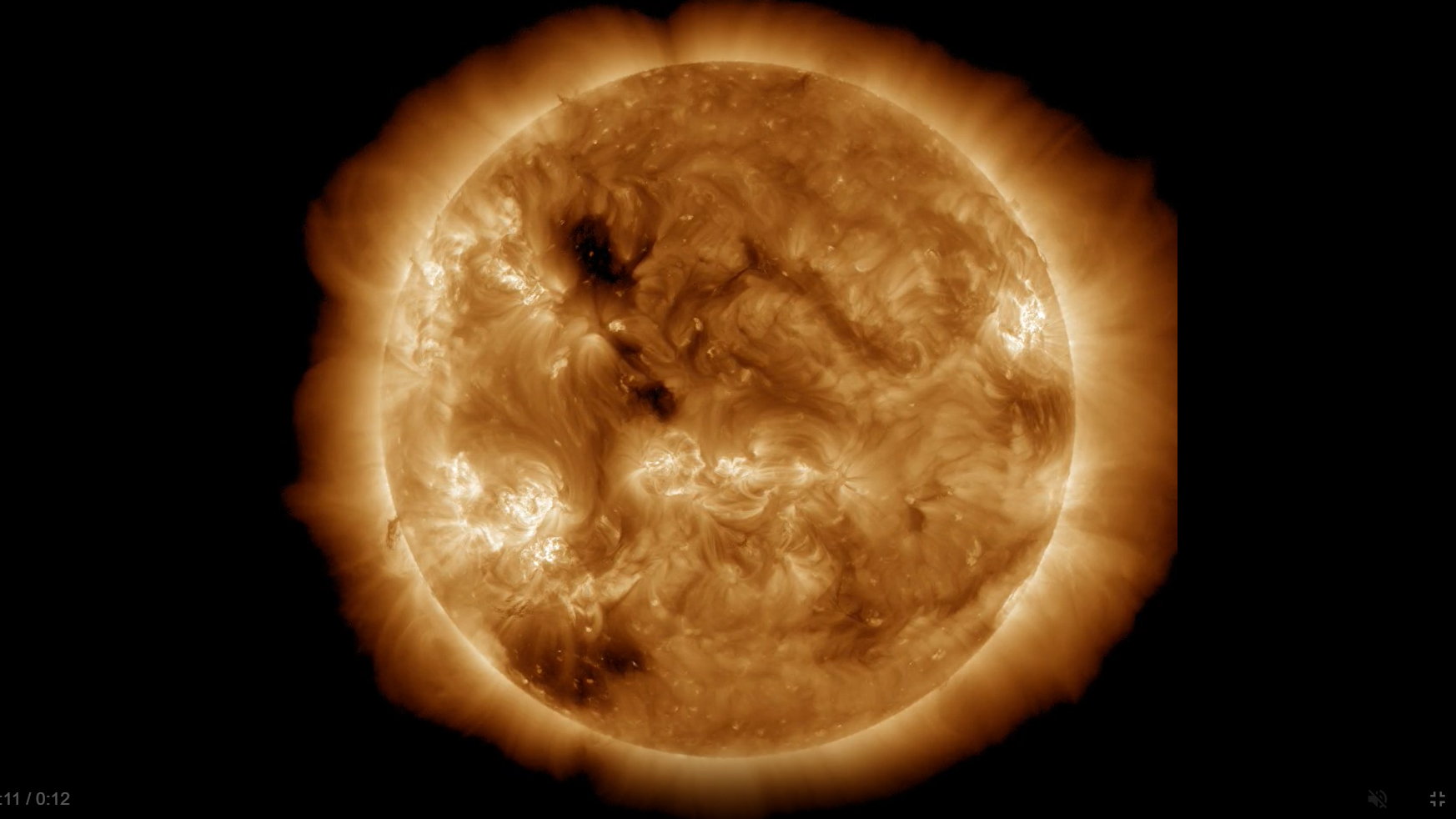

In the meantime, space weather forecasters continue to monitor the sunspot that sparked yesterday's flare as well as several other sunspots that are brewing on the sun's face. The forecasters warn that more solar fireworks are possible in the week ahead. So far, no coronal mass ejection is heading our way but auroras may get a boost from high speed solar wind streaming from a hole in the sun's magnetic field, the U.K. space weather forecaster Met Office said in a statement.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.