Solar activity may peak 1 year earlier than thought. Here is what it means for us

A team of researchers who had previously issued an alternative solar forecast that turned out to be better than NASA's claims the sun's activity will peak next year.

The sun may reach the peak of its current activity cycle in 2024, one year ahead of official predictions, new research suggests. But even after the sun reaches its peak, its wrath will continue to threaten Earth for at least the next five years.

A team of researchers who had previously released an alternative solar cycle prediction that turned out to be more accurate than official forecasts by NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) recently published improved estimates of the current solar cycle's strength and progress.

The team's finalized forecast for the current cycle expects it to peak in late 2024, one year earlier than NASA and NOAA had predicted. The cycle, the team thinks, will reach about 185 monthly sunspots during its solar maximum and thus be somewhat milder than what the team originally forecasted. This peak intensity will place this cycle at about the average compared to the historical record.

Related: Extreme solar storms can strike out of the blue. Are we really prepared?

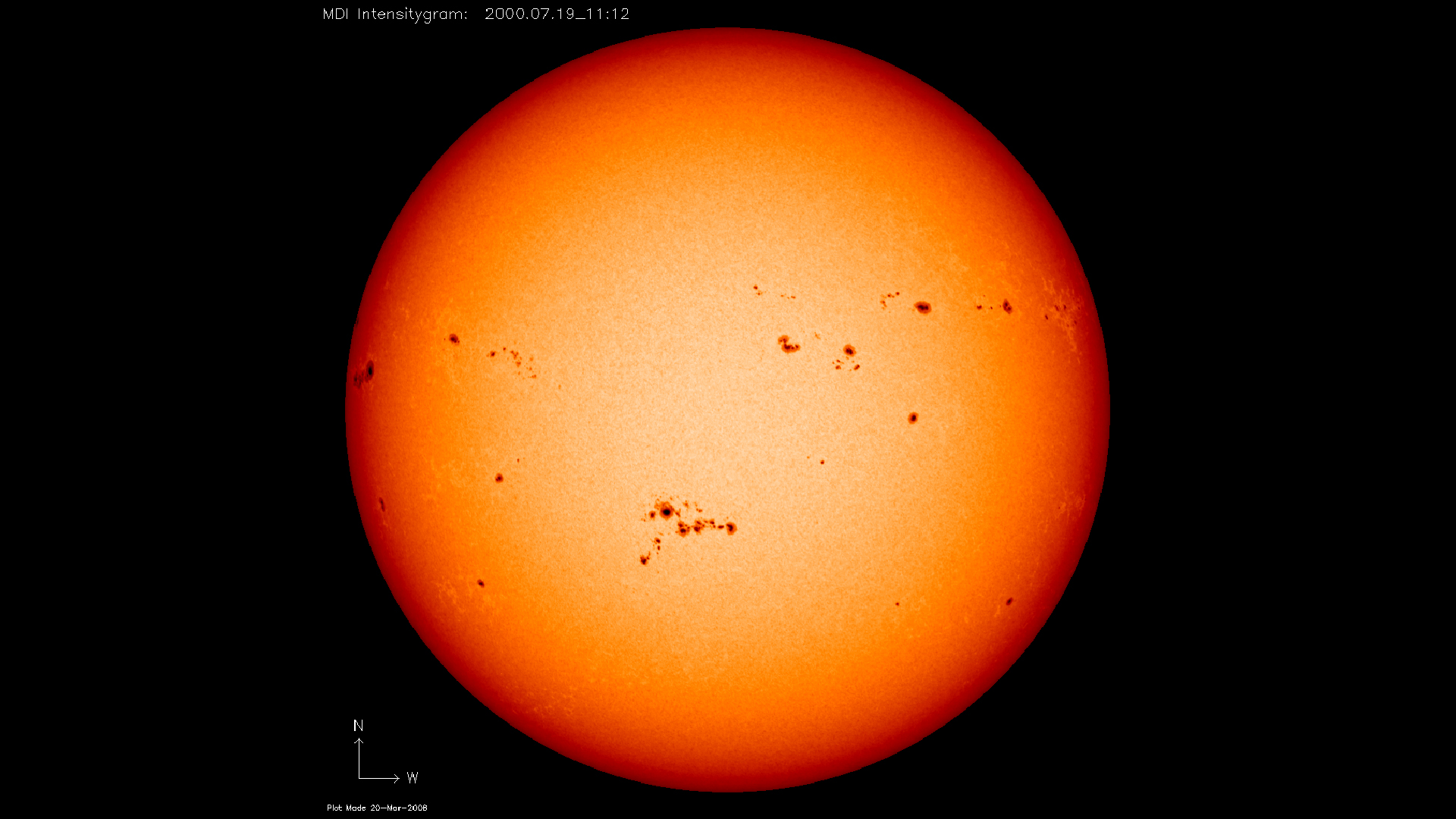

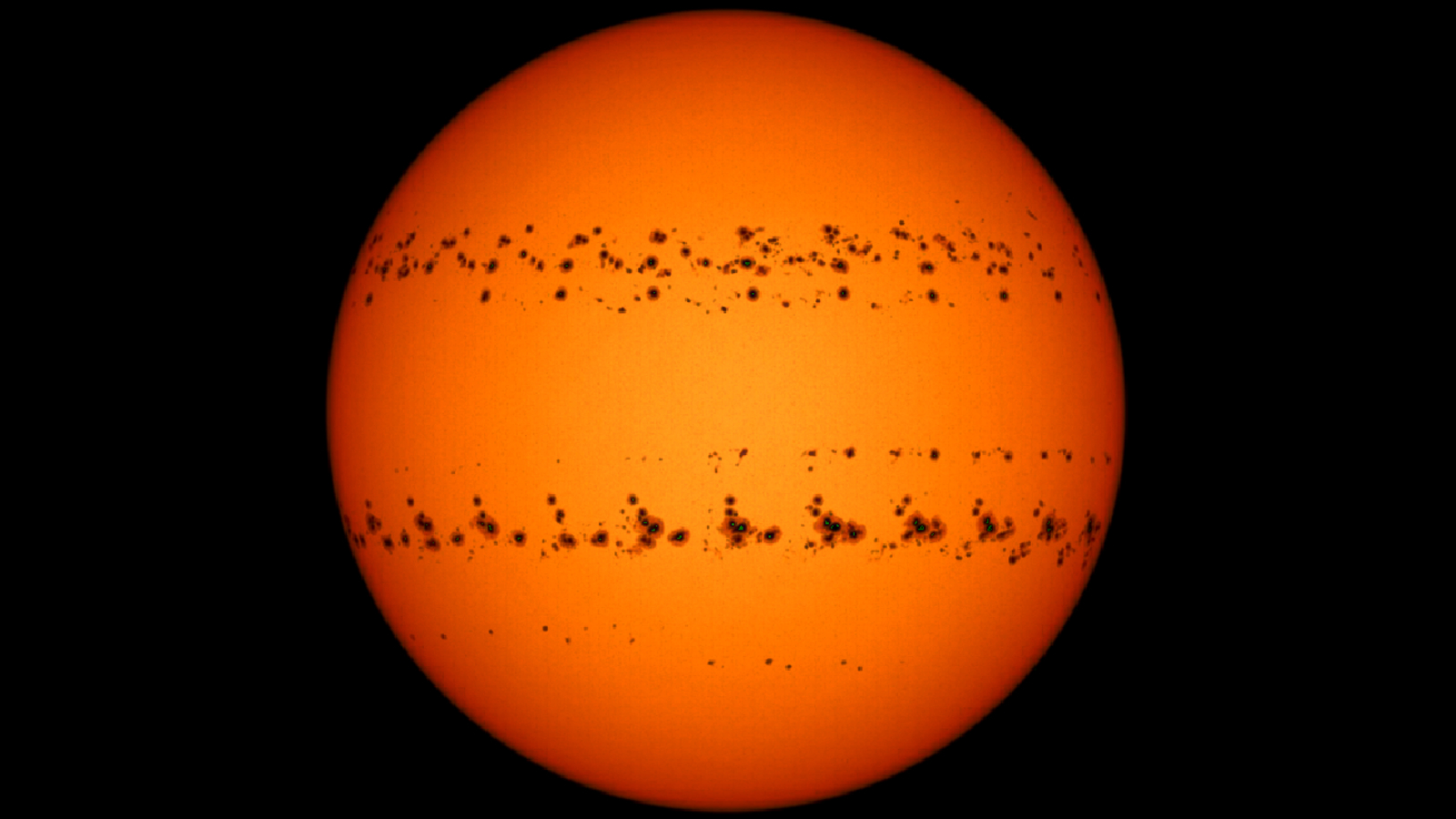

The current cycle, the 25th since records began in 1755, kicked off in 2019 and, according to official predictions, was supposed to be extremely mild, peaking with about 115 monthly sunspots in 2025. The solar cycle is the approximately 11-year ebb and flow in the sun's magnetic activity that manifests in the number of sunspots, solar flares and eruptions. These cycles vary in intensity, with the weakest on record having produced less than a hundred spots per month during the maximum and the strongest peaking with nearly 300.

Cycle 25 followed the extremely weak Cycle 24, and NASA and NOAA thought it would be just as underwhelming. However, since Cycle 25 picked up momentum in 2022, it has been steadily outpacing the official predictions in line with the alternative forecast issued by a team led by NASA research scientist Robert Leamon and Scott McIntosh, the deputy director at U.S. National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

But why do Leamon and McIntosh's results diverge so much from the official estimates, and why are they closer to reality than what the bigwigs agreed on? It turns out that solar cycle forecasting is still rather crude and with only 25 cycles on record, the amount of data available for computer modeling is limited.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In their studies, Leamon and McIntosh therefore explore alternative ways of predicting the sun's behavior based on the star's magnetic activity. By analyzing historical records, they found that the strength of every subsequent cycle depends on the time when the magnetic field of the previous cycle completely dies. This event, which the team dubbed the terminator, doesn't happen exactly at the minimum, but up to two years later when the next solar cycle is slowly waking up.

"There's always the overlap between the old and the new," Leamon told Space.com.

The researchers think that understanding solar cycles not as framed by the miminums but rather by the terminator events can produce more accurate predictions.

"If you measure how long a cycle is, not the minimum to minimum, but from terminator to terminator, you see that there is a strong linear relationship between how long one cycle is and how strong the next one is going to be," said Leamon.

The original prediction Leamon and his colleagues made was based on the expectation that the terminator event ending Cycle 24 would arrive in mid-2020, which would suggest a very strong Cycle 25. Cycle 24, however, ended up lingering for a year and half longer, with its magnetic field eventually completely disappearing in December 2021.

"When the [terminator] event actually happened, we changed the input and that gave us a somewhat milder prediction than what we expected originally," said Leamon.

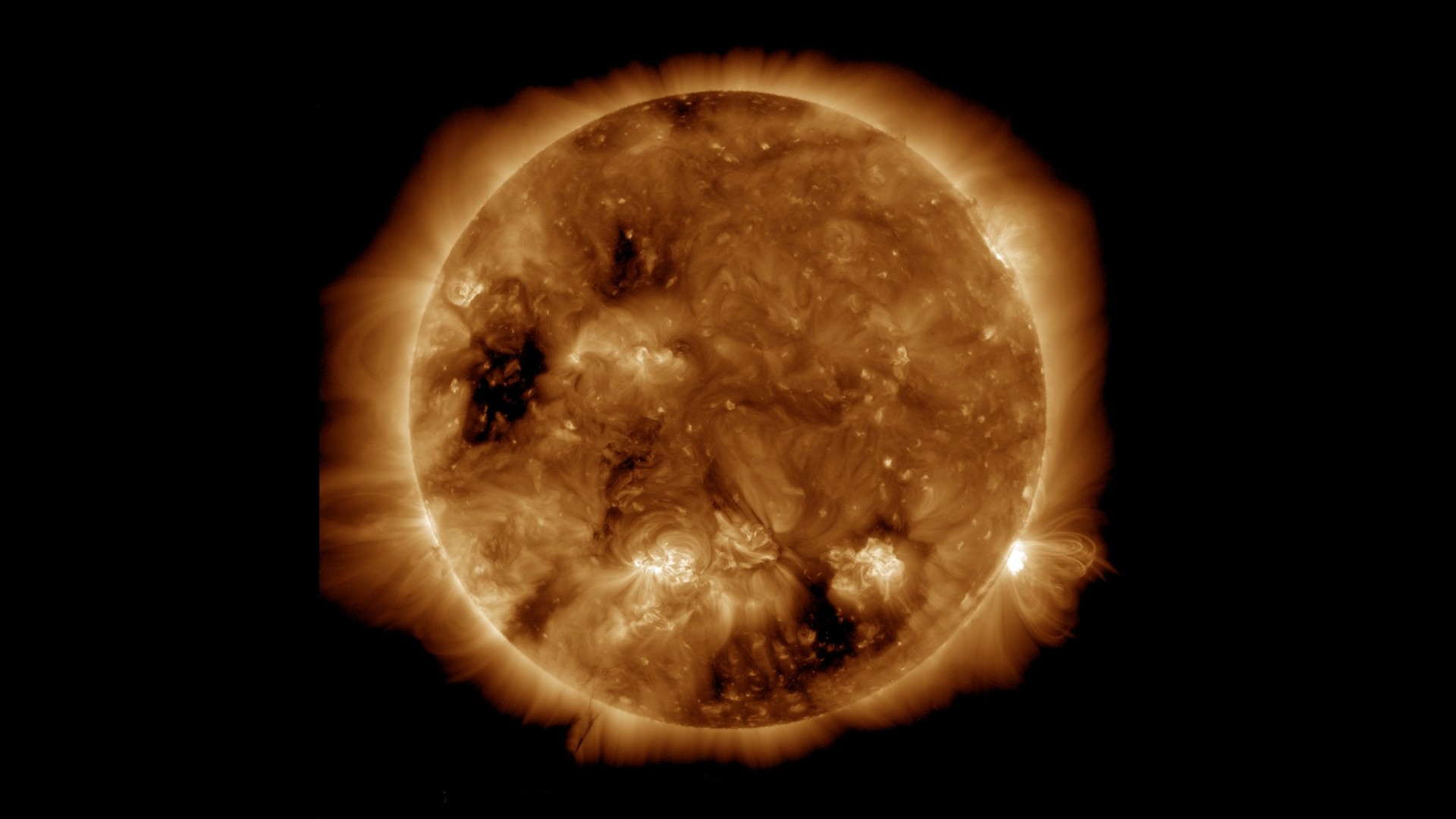

The terminator events are part of what scientists call the Hale cycle, a 22-year cycle of magnetic activity that encompasses two 11-year solar cycles. During the Hale cycle, magnetic waves of opposing polarity move from the sun's poles toward the equator where they meet and cancel each other out. When these magnetic field lines are about halfway through their journey, the sun's magnetic field flips, which corresponds with the approximate time of the solar maximum. The Hale cycle is complete when the magnetic field returns to its original state after two solar cycles. The terminator, the canceling out of the magnetic waves at the equator, can be observed in historical records of sunspot generation as a complete disappearance of sun spots in the star's equatorial region.

Based on their calculations, Leamon and his colleagues expect the sun's magnetic field to flip in mid-2024, with the solar maximum of the current solar cycle to arrive a few months later.

For us on Earth, that means we are likely heading into a period of more frequent and more intense aurora displays, but also of more intense space weather events that can create trouble in Earth's orbit. Auroras are produced from the interactions between material that flows from the sun and Earth's magnetic field. Similar reactions that produce these stunning natural light shows, however, thicken Earth's residual atmosphere at high altitudes where satellites orbit. That leads to increased drag that can cause satellites to fall from orbit, among other problems. In February 2022, SpaceX lost a batch of 40 brand new Starlink satellites after launching them into what forecasters considered to be only a mild solar storm.

The arrival of the solar maximum will not mean that we will be out of the woods when it comes to the risk of disruptive space weather events. Leamon said that according to available data, powerful solar flares and eruptions frequently take place on the downside of odd-numbered cycles, such as the current Cycle 25. In the case of even-numbered cycles, the risk of dangerous solar storms is highest during the first part of the cycle.

"Since Cycle 25 is odd, we might expect the most effective events to happen after the maximum, in 2025 and 2026," said Leamon. "This is because how the poles of the sun flip every 11 years. You want the pole of the sun in the same orientation compared to the poles of Earth so that then causes the most damage and the best coupling from the solar wind through Earth's magnetic field."

The biggest solar storms of the current cycle, Leamon added, are therefore mostly likely going to happen after the maximum.

"We need to be vigilant for about five more years," he said.

The team's latest forecast was published in January in the journal Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.