Dark matter data salvaged from balloon-borne telescope that landed hard on Earth

'Our telescope got to the point where it was completely destroyed.'

A NASA telescope that launched on a football-stadium-sized balloon earlier this year lost communication with Earth and suffered damage upon landing in Argentina in June.

Luckily, the data it had collected — 200 gigabytes' worth of stunning images of galaxy clusters taken while floating 100,000 feet (30,000 meters) above Earth's surface — had been copied to old-fashioned SD drives and parachuted to the ground safely, showing that valuable science data can be salvaged even in a "worst-case scenario," scientists reported on Tuesday (Nov. 14).

The $10 million balloon-borne observatory, known as the Super Pressure Balloon Imaging Telescope (SuperBIT), was designed to give astronomers pocket-friendly observations of celestial objects. The main goal was to help map dark matter around galaxy clusters, primarily by measuring how the celestial objects warp space and time around them.

Related: Meet SuperBIT, the next-generation telescope that rides above the clouds on a balloon

After lifting off in April from Wānaka Airport in New Zealand, SuperBIT circled Earth about five times to capture images of its galaxy cluster targets in visible to near-ultraviolet light wavelengths. Its targets included the star-forming regions of the Tarantula Nebula 161,000 light-years from Earth, the two colliding Antennae galaxies 60 million light-years away and the Pinwheel spiral galaxy, among others.

SuperBIT's planned 100-day-long mission was shortened to 40 days due to "conflicting wind predictions," at which point the telescope made its way back to the targeted landing spot, a remote hill in Argentina. Upon touchdown, however, the parachute failed to disconnect from its payload after an equipment failure, dragging the telescope over rough terrain for a couple of kilometers while high winds blew overhead.

"Our telescope got to the point where it was completely destroyed, and we lost high-bandwidth communications," Ellen Sirks of the University of Sydney, lead author of the new SuperBIT study, said in a statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Usually, data gathered by balloon-borne telescopes like SuperBIT is downloaded using a satellite, but quick downloads require line-of-sight communications, something that is not always feasible.

"In our case, we were getting so much data per night that it would just be incredibly slow and expensive to retrieve this data mid-flight," Sirks said. "At the moment, the most efficient way for us to download data is to copy it onto an SD drive and just drop it to Earth, which is kind of crazy, but it works well."

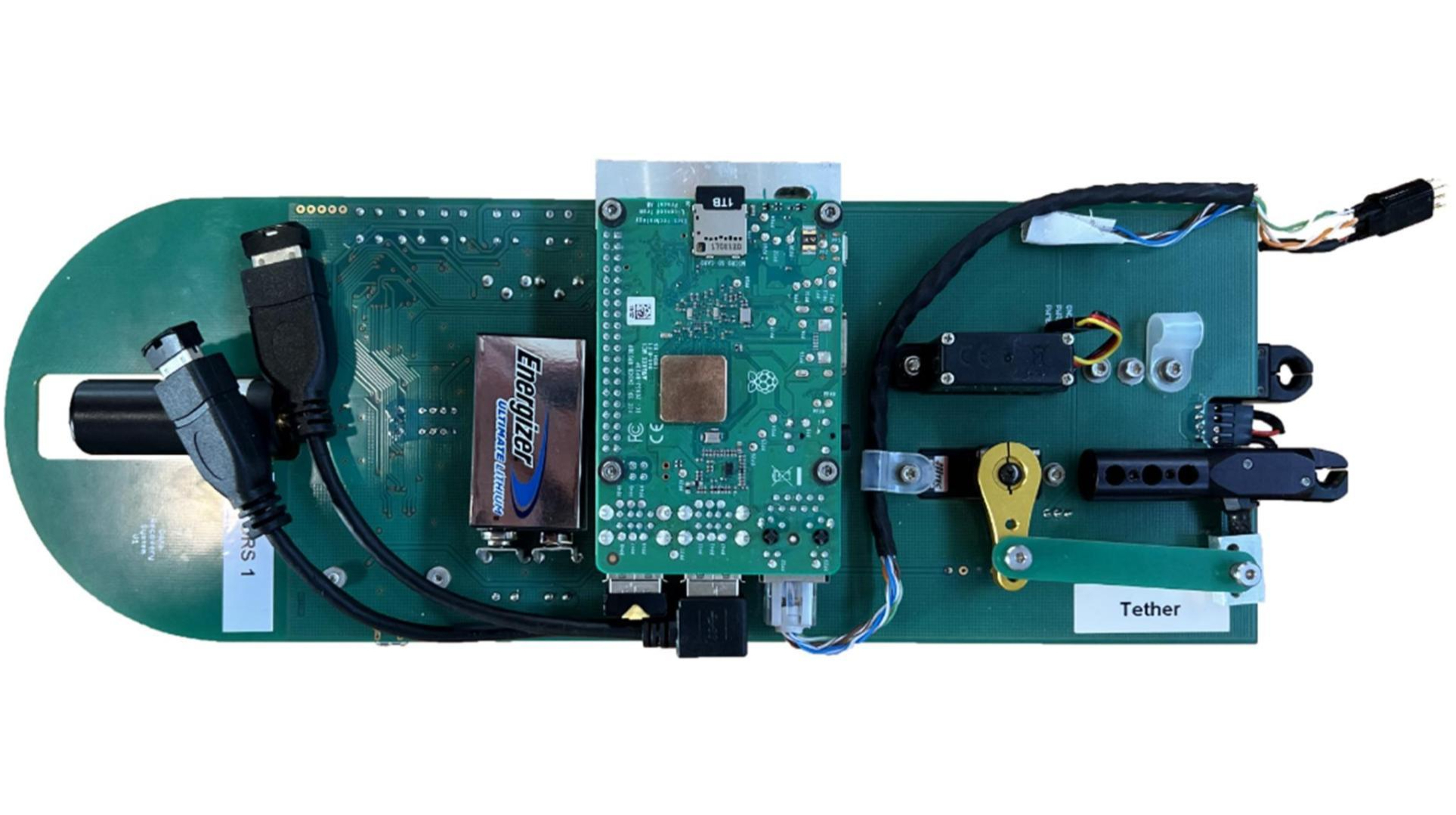

So she and her colleagues from Australia, the U.K., the U.S., Canada, Europe and Taiwan developed "recovery packages" consisting of tiny computers with SD cards that store data, a homemade satellite link for communication with the telescope and parachutes sheathed in waterproof chicken roasting bags.

Retrieving SuperBIT's recovery package from the Argentinian countryside was a mission in itself and included help from the local police, scientists involved with the mission say.

"We couldn't find one at first, and when we did, there were cougar tracks in the snow near it, so we thought maybe the chicken roast bag was not the best idea," said Sirks. "It was quite funny. But we did retrieve them quite easily."

Although Sirks and her team have been developing this system for about five years, the recent mission marked the first time they tested it in its final configuration. Not only did it work, Sirks said, "it was really quite essential to the mission's success."

"It's got to the point where NASA wants to start producing these packages for other science missions as well, so this was really our final test to show that this system works."

This research is described in a paper published on Tuesday in the journal Aerospace.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social