On Tuesday, Feb. 19, you'll no doubt hear the mainstream media proclaiming that on that night Earthlings will witness a "supermoon."

It's a term — or, more specifically, a branding — of relatively recent origin; it came not from astronomy, but astrology, and was coined by astrologer Richard Nolle in 1979. Nolle arbitrarily defined a supermoon as a new or full moon that occurs when the natural satellite is at or near (within 90 percent of) its closest approach to Earth in a given orbit (perigee).

Interestingly, nobody paid much attention to Nolle's definition until March 19, 2011, when the full moon arrived at an exceptionally close perigee, coming within 126 miles (203 kilometers) of its closest possible approach to Earth.

Suddenly, the term "supermoon" went viral. But why? [How the 'Supermoon' Looks (Infographic)]

Likely, it was due to an event that happened eight days earlier, on March 11 of that year: the Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which registered 9.1 on the Richter scale; in its aftermath, some speculated that the moon's gravitational pull could trigger earthquakes. And because the moon will be unusually close to Earth on Feb. 19, people have inferred that more potent quakes are possible with the upcoming supermoon.

Nolle, in his website back in 2011,said, there will be "a major geophysical stress window, centered on the actual alignment date but in effect from the 16th [of March] through the 22nd; you can expect a rash of moderate-to-severe seismic activity (including Richter 5+ earthquakes, tsunami and volcanic eruptions)." For many people, it seemed Nolle had presaged the deadly 2011 event in Japan.

Despite Nolle's comment, there is absolutely no solid scientific correlation between earthquakes and the moon's distance from the Earth. (And there were no significant quakes, tsunami or volcanic eruptions from March 16t to 22, 2011.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Nevertheless, in anticipation of the March 19, 2011, full moon, somebody doing some research dredged up Nolle's "supermoon" definition and launched what I refer to as the "supermoon syndrome."

Supermoon branding "watered down"

For years, astronomers classified a full moon that coincided with perigee as a "perigean full moon," a term that received little or no fanfare.

Now, it seems that every time a full moon coincides with perigee, it is referred to as a supermoon. Once a year, the moon turns full within several hours of perigee; after next Tuesday, the next time this will occur will be on April 7, 2020.

And yet, last month's full moon, on Jan. 20, which occurred about 15 hours before perigee, and next month's full moon, on March 20, which comes nearly 26 hours after perigee, are also being branded as supermoons. That's seemingly because they fall within 90 percent of the moon's closest approach to Earth — or, in other words, within the top 10 percent of the closest full moons.

Even some reputable astronomy sites endorse this definition.

So now, in most years, we have not just one but three supermoons.

But just how "super" is that?

Unrealistic expectations

If you step outside and look at the moon on Tuesday night and expect to see something special, you'll likely be disappointed. At least last month's so-called supermoon was accompanied by a total lunar eclipse. Still, tons of images are posted to the internet in advance of a supermoon, depicting exceedingly large, full moons from images taken with telephoto lenses, implying that the moon is going to look amazingly large in the sky.

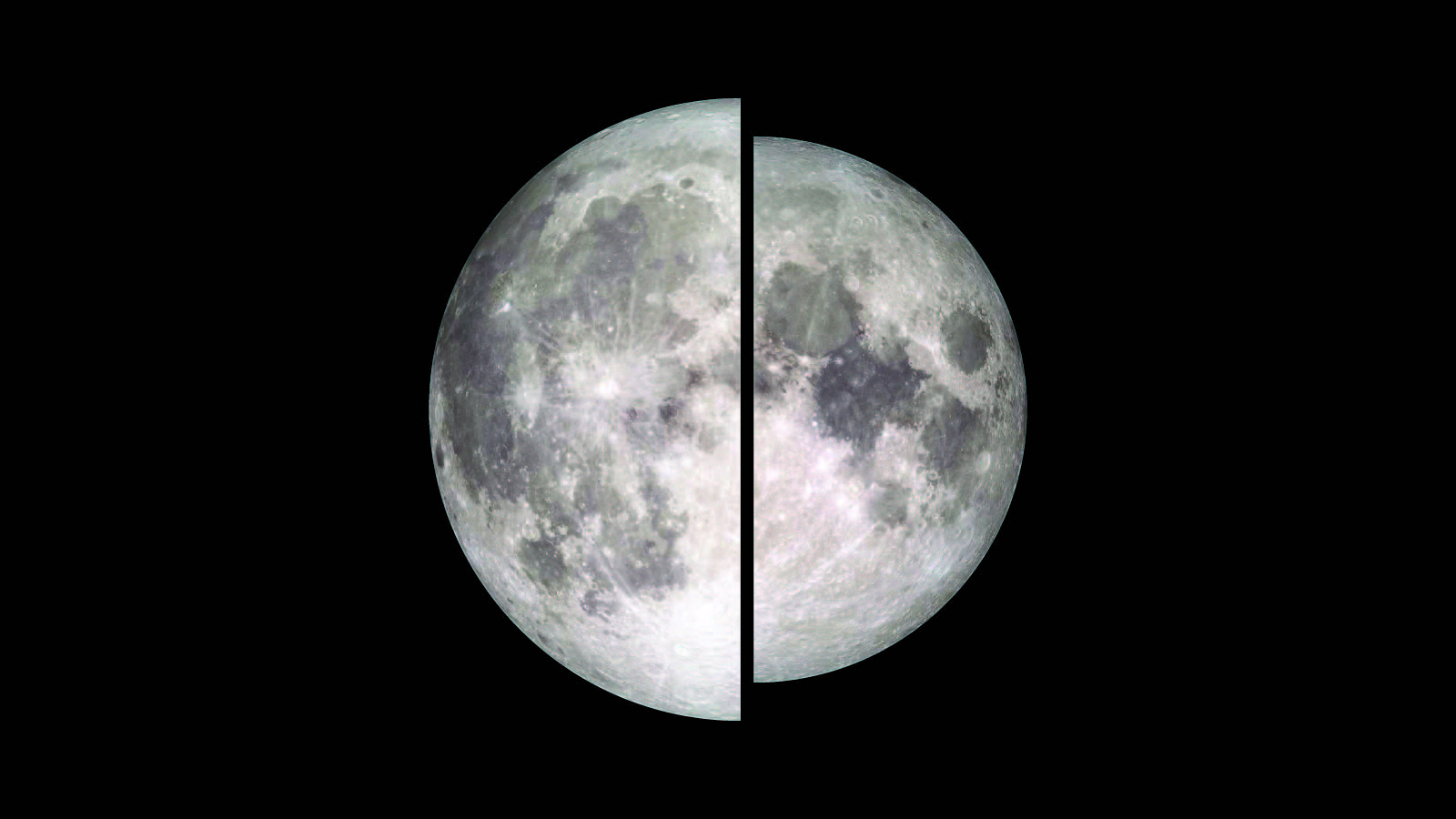

At its closest on Tuesday, the moon will be 221,681 miles (356,761 km) from Earth. But that's only 7.2 percent closer than the natural satellite's average distance from our planet. So, while Tuesday's moon will indeed be the "biggest" in apparent size, unless you catch the moon when it's either rising or setting — and appearing briefly larger than normal because of the famous "moon illusion" — Tuesday's full moon will look pretty much like any other full moon.

In fact, in an "official" sense, that Tuesday night moon will not be full at all!

Full moon on Tuesday will occur at 10:54 a.m. EST (1554 GMT) — during the daytime, with the moon below the horizon — so Americans will not get to see the exact moment that the moon is full. When the moon comes above your local horizon on Tuesday evening, technically you'll be looking not at a "full" moon, but a waning gibbous moon. Though a full moon theoretically lasts just a moment, that moment is imperceptible to ordinary observation. And so, for a day or so before and after the moment of full moon, most will speak of the nearly full moon as being "full." During these times, the shaded strip on the moon is so narrow, and changing in apparent width so slowly, that it is hard for the naked eye to tell whether the darkened section present or on which side it is located. [Full Moon Calendar: When to See the Next Full Moon]

Then, there is the issue of the moon's brightness. Some think that they will see an exceptionally dazzling full moon come Tuesday night. Back in 2013, a friend of mine told me that she was expecting year's version of the supermoon"to look "radically brighter ..., like with those three-way lightbulbs, I thought it was going to be like turning the moonlight up a notch."

Some websites, including Spaceweather.com, speak of the supermoon as appearing "30 percent brighter than other full moons."

But that comes out to a minuscule increase of less than three-tenths of a magnitude; the moonlight on Tuesday night will not be exceptionally bright.

Effect on the tides

About the only effect of Tuesday's supermoon that we'll be able to notice directly is its influence on the tides. The near coincidence of Tuesday's full moon with perigee will result in a dramatically large range of high and low ocean tides. Any coastal storm at sea around this time will almost certainly aggravate coastal flooding problems. Such an extreme tide is known as a perigean "spring" tide, the word spring deriving from the German "springen," meaning to "spring up." It's not a reference to the spring season.

The supermoon's influence on tides is explained by a simple physics equation. Tidal force varies as the inverse cube of an object's distance from the ocean. On Tuesday, the full moon will be 12.3 percent closer to Earth compared to the full moon of Sept. 14, which will most nearly coincide with apogee (the moon's farthest point from the Earth). Therefore, the moon will exert about 42 percent more tidal force during the spring tides of Feb. 19 than during the spring tides accompanying the September full moon.

A quick check at the tide tables bears this out. At Boston Harbor on Feb. 20, at high tide around 11:30 a.m. EST, the tide height is predicted to be 12.1 feet (3.7 meters). Compare this to the spring tides occurring on Sept. 16, which will run more than 2 feet (0.6 m) lower. Take note that there is a lag of approximately one to two days between the time of perigee or apogee and their effects on the maximum height of water levels at high tide.

For some places, the tidal differences will be less; for others, they will be greater; it depends chiefly on the topography of the seacoast.

Minas Basin, the eastern extremity of the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, is especially sensitive to the perigee-apogee influence of the moon. As Roy Bishop points out in the 2019 "Observer's Handbook" of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, "To those living near the head of the Bay of Fundy, the 10- to 20-foot (3 to 6 meter) increase in the vertical tidal range makes it obvious when the moon lies near perigee, clear skies or cloudy!"

Editor's note: If you capture an amazing photo of the February Full Moon and would like to share it with Space.com for a story or gallery, send images and comments to at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon FiOS1 News in New York's lower Hudson Valley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.