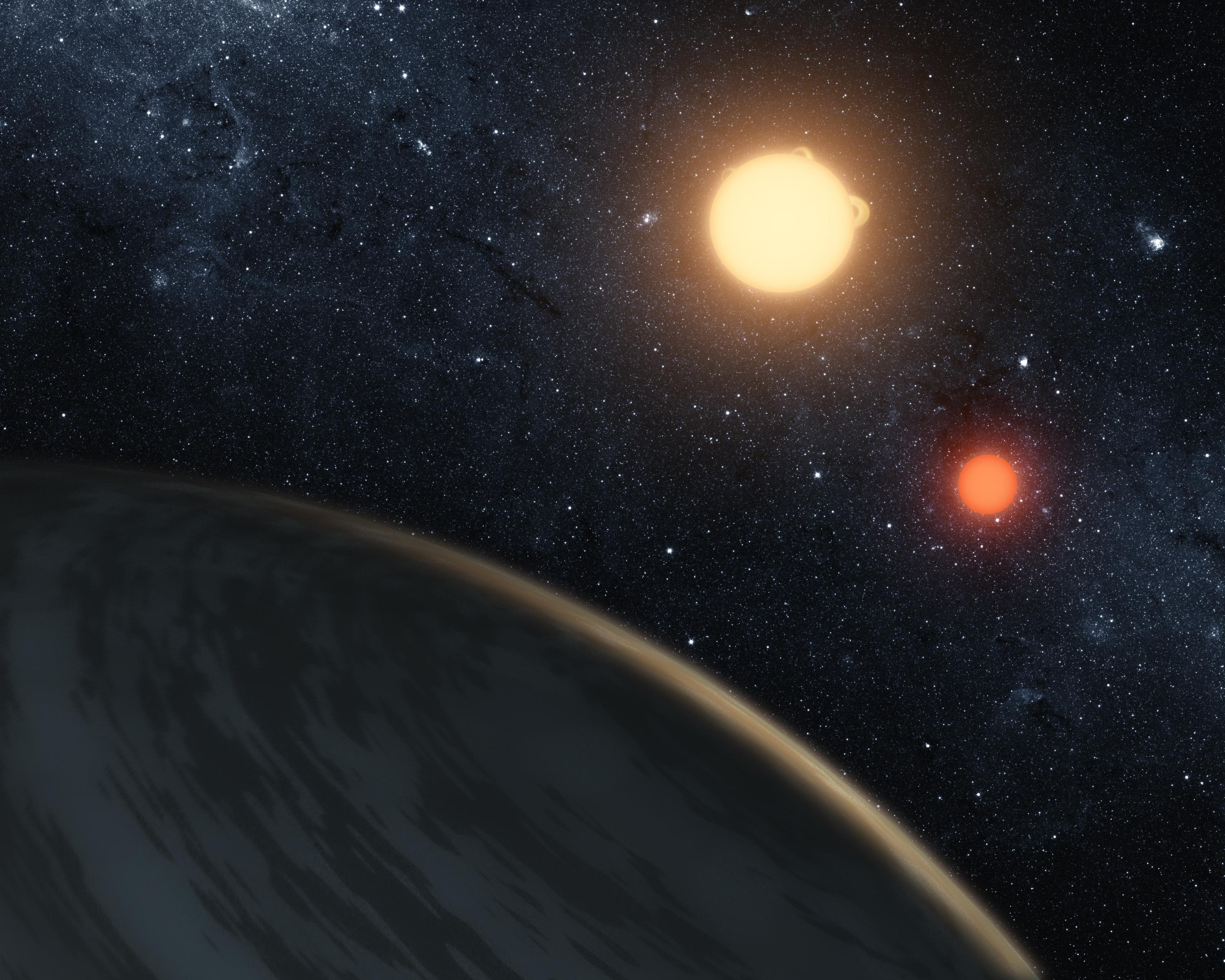

'Tatooine-like' planet spotted from Earth points to future discoveries

Astronomers want to spot more such worlds with double sunrises.

A ground-based telescope's detection of a known Tatooine-like planet could herald new discoveries of similar planets, researchers say.

Observers spotted Kepler-16b — an exoplanet that orbits two stars, similar to a world portrayed in the original series of "Star Wars" — using a relatively modest 75-inch (193-centimeter) telescope. The telescope is situated at Observatoire de Haute-Provence, roughly 60 miles (100 kilometers) north of Marseilles, France. The University of Birmingham-led research team said that the detection shows the value of using a ground-based telescope "at greater efficiency and lower cost than by using spacecraft."

The planet was originally found in space using the transit method, during which the planet passed in front of one of its stars in front of the now-retired NASA Kepler space telescope. The France-based telescope confirmed the world through the radial velocity method, which looks at the gravitational tugs a planet induces on its parent star or stars.

Related: The strangest alien planets (gallery)

The team says the discovery heralds a new series of work they plan to perform concerning so-called "circumbinary planets," meaning planets that orbit two stars.

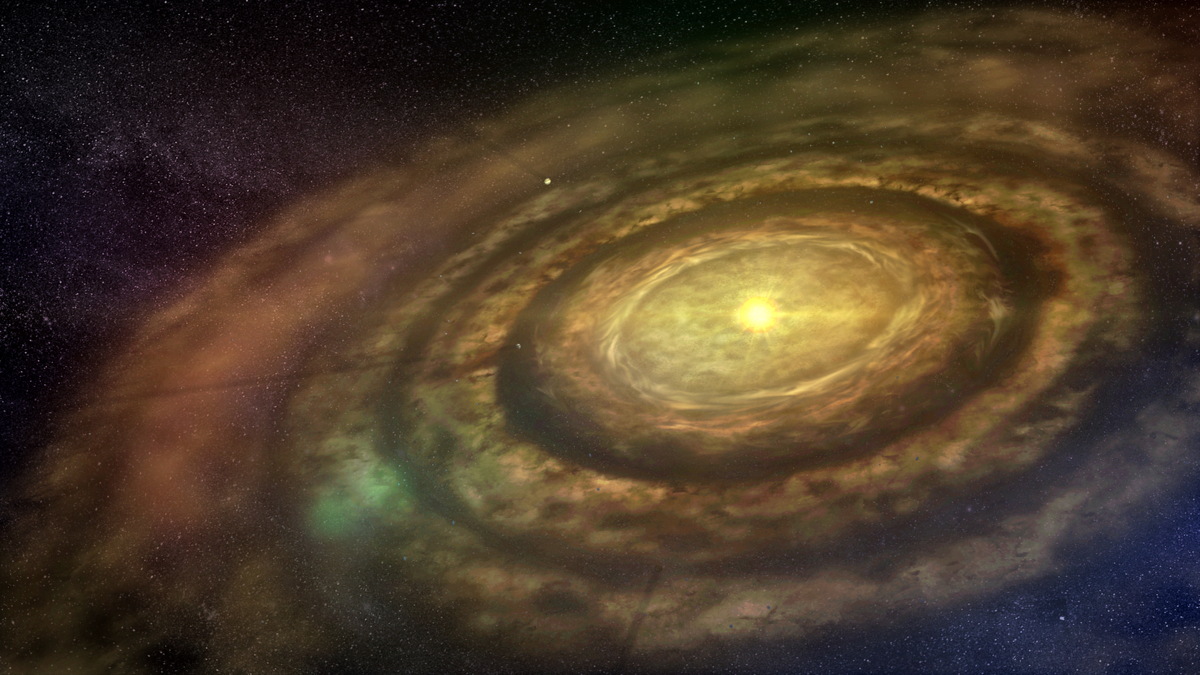

The scientists hope their telescope will next find previously unknown planets of this type, helping astronomers learn how planetary formation occurs in a solar system with two stars. Traditionally, planets are believed to form in a protoplanetary disk of gas and dust surrounding a young star, but it's not clear if circumbinary systems could support this environment.

"Using this standard explanation, it is difficult to understand how circumbinary planets can exist," lead author Amaury Triaud, a Birmingham exoplanet researcher, said in the statement. "That's because the presence of two stars interferes with the protoplanetary disk, and this prevents dust from agglomerating into planets, a process called accretion."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Triaud suggested the planet might have instead formed far away from the two stars and then migrated inward. But more study could reveal alternate scenarios forming double-starred planets, which in turn may shape scientists' theories about how planets form more generally.

A study based on the research was published Tuesday (Feb. 22) in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.