Taurid meteor shower 2025: When, where and how to see it

Viewing conditions for the Taurids are good for the Southern Taurids but may wash out the Northern Taurids this year.

The Taurid meteor shower, consisting of the Southern Taurids and Northern Taurids, is a highlight for stargazers each fall.

This year, the Southern Taurids will be active between Sept. 10 and Nov. 20, peaking around Oct. 10. Whereas the Northern Taurids will be active between Oct. 20 and Dec. 10, peaking around Nov. 12, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. The Taurids are generally more noticeable around late October to early November when they overlap.

These showers, known for their slow-moving, long-lasting meteors, are linked to comet Encke, which has a nucleus approximately 2.98 miles (4.8 km) in diameter.

"The Taurids are rich in fireballs, so if you see a Taurid it can be very brilliant and it'll knock your eyes out, but their rates absolutely suck," NASA meteor expert Bill Cooke told Space.com. "It's simply the fact that when a Taurid appears it's usually big and bright." Typically, the Taurids produce only a handful of visible meteors per hour.

As the Taurids occur in late October they are sometimes referred to as "Halloween fireballs".

Taurid meteors tend to be larger than other meteors and can survive for longer periods as they pass through Earth's atmosphere. According to NASA, Orionids for example, typically burn up at altitudes around 58 miles (93 km) whereas Taurids typically make it as far as 42 miles (66 km). They also travel relatively slowly, traversing the sky at about 17 miles (27 kilometers) per second or 65,000 miles (104,000 km) per hour. The Perseids, on the other hand, zip through the sky at 37 miles (59 km) per second.

Where can you see the Taurid meteor shower?

Right ascension: 4 hours

Declination: 15 degrees

Visible between: Latitudes 90 degrees and minus 65 degrees

The Taurids are visible practically anywhere on Earth, except for the South Pole. Meteor showers are named after the constellation from which the meteors appear to emanate, known as the radiant. From Earth's perspective, the Taurid meteor shower appears to come approximately from the direction of the Taurus constellation.

To find Taurus, look for the constellation Orion and then peer to the northeast to find the red star Aldebaran, the star in the bull's eye.

Don't look directly at Taurus to find meteors; the shooting stars will be visible all over the night sky. Make sure to move your gaze around the nearby constellations. Meteors closer to the radiant have shorter trails and are more difficult to spot. If you look only at Taurus, you might miss the shooting stars with the most spectacular trails.

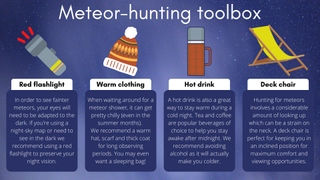

To see the Taurids meteor shower at its best, go to the darkest possible location, lean back and relax. You don't need any equipment like telescopes or binoculars as the secret is to take in as much sky as possible and allow about 30 minutes for your eyes to adjust to the dark.

If you want more advice on how to photograph the Taurids, check out our how to photograph meteors and meteor showers guide and if you need imaging gear, consider our best cameras for astrophotography and best lenses for astrophotography.

When is the best time to view the Taurid meteor shower?

The best time to view the Taurid meteor shower — both the northern and southern streams — is around midnight when the shower's radiant, the Taurus constellation, is high in the sky.

the Southern Taurids will be active between Sept. 10 and Nov. 20, peaking around Oct. 10. Whereas the Northern Taurids will be active between Oct. 20 and Dec. 10, peaking around Nov. 12, according to the Royal Museums Greenwich. The Taurids are generally more noticeable around late October to early November when they overlap.

The best time to view the Taurids will be around midnight on Nov. 5, 2025, when the waxing gibbous moon has either set or is lower in the sky, according to EarthSky.

To calculate sunrise and moonrise times in your location check out this custom sunrise-sunset calculator.

What causes the Taurid meteor shower?

The Taurid meteor shower is caused by the debris — ice and dust — from comet 2P/Encke as it passes through our solar system.

The debris stream from Encke is so large and spread out that it takes Earth a rather long time to pass through the entirety of the debris which is why we experience two separate segments of the shower — the Northern Taurids and the Southern Taurids, according to Royal Museums Greenwich (RMG).

Comet Encke was discovered by French astronomer Pierre F. A. Mechain on Jan. 17, 1786, according to NASA Science. Usually, comets are named after their discoverers or the observatory or telescope involved in the discovery. However, Comet Encke was named after German astronomer Johann Franz Encke who was responsible for calculating the comet's orbit.

Encke has the shortest orbital period of any known comet within our solar system, taking just 3.3 years to orbit the sun.

Each time comet Encke returns to the inner solar system, its nucleus sheds ice and rock into space into a vast debris stream. When Earth passes through the debris the "comet crumbs" heat up as they enter Earth's atmosphere and burn up in bright bursts of light, streaking a vivid path across the sky.

Comet Encke and the Taurid meteor shower are thought to be the remnants of a far larger comet that broke apart over the last 20,000 to 30,000 years, according to RMG.

Additional information

Learn more about the French astronomer Pierre F. A. Mechain with this biography from the University of St. Andrews. Discover more about Taurid fireball activity since 1962 with this comprehensive review of the Taurids. Explore the Taurus constellation and find out how to spot it with the unaided eye with skywatching website In-The-Sky.org.

Bibliography

NASA. 2P/Encke. NASA. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/asteroids-comets-and-meteors/comets/2p-encke/in-depth/

NASA. Taurid Meteor — watch the skies. NASA. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://blogs.nasa.gov/Watch_the_Skies/tag/taurid-meteor/

Taurid meteor shower 2022: When and where to see it in the UK. Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://www.rmg.co.uk/stories/topics/taurid-meteor-shower-2022-when-where-see-it-uk

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master's in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K. Daisy is passionate about all things space, with a penchant for solar activity and space weather. She has a strong interest in astrotourism and loves nothing more than a good northern lights chase!