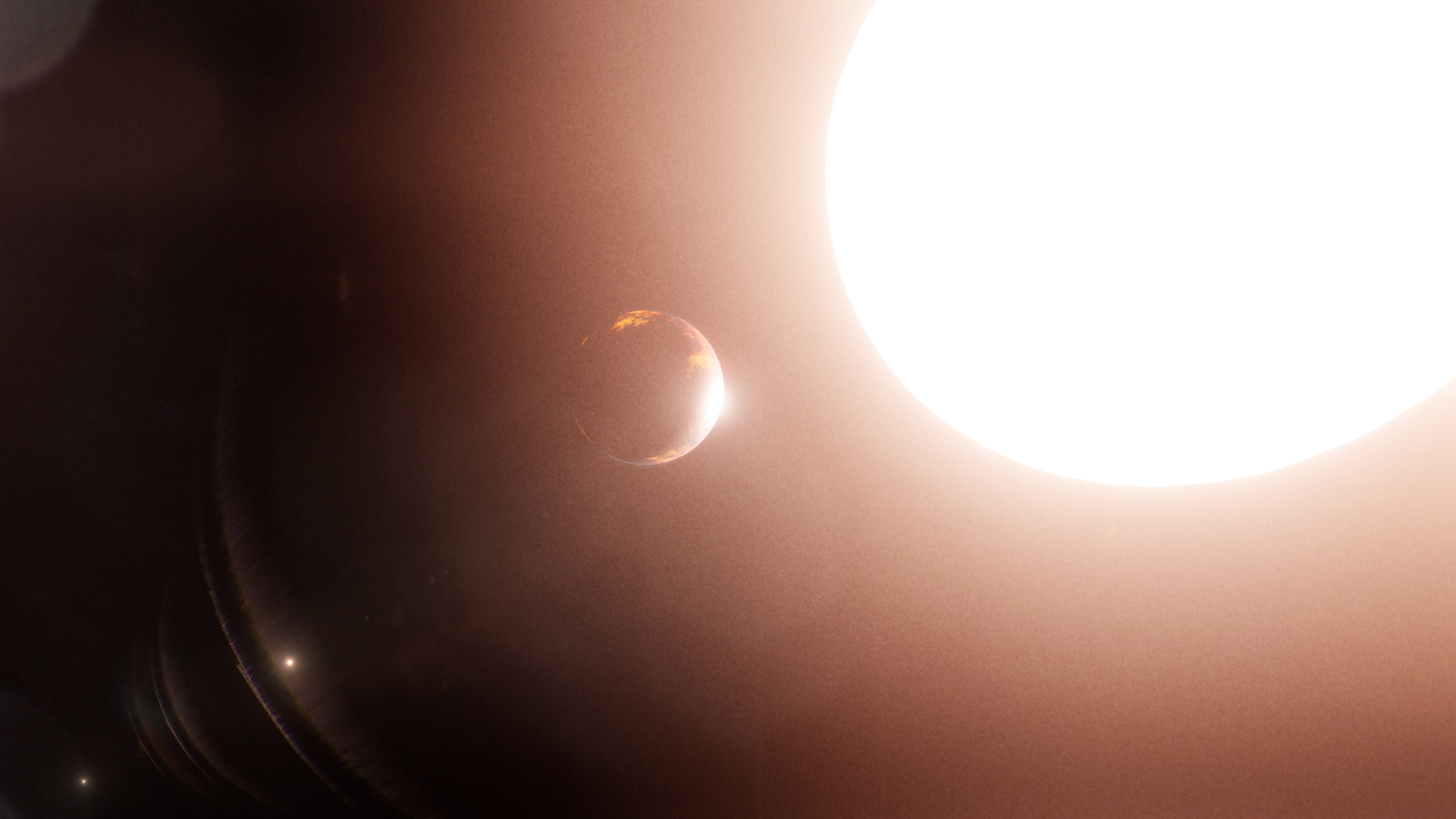

Astronomers have discovered a quartet of teenage exoplanets, according to data from NASA's TESS mission.

The planets in question lie a bit over 130 light-years away from Earth. They orbit a pair of little orange dwarf stars, each smaller than the sun, named TOI 2076 and TOI 1808. (TOI is short for TESS Object of Interest.) Even though the two stars are not close — they're a whole 30 light-years apart, actually — they're moving in the same direction, and are both around the same age, suggesting that they formed in the same place.

"The planets in both systems are in a transitional, or teenage, phase of their life cycle," Christina Hedges, an astronomer at the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute and NASA's Ames Research Center in California, said in a statement. "They're not newborns, but they're also not settled down. Learning more about planets in this teen stage will ultimately help us understand older planets in other systems."

Related: NASA's TESS exoplanet-hunting mission in pictures

Since 2018, NASA's TESS ( the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) telescope has been in Earth orbit keeping an eye on 75% of the visible sky. It watches for subtle dips in light from stars, which can be telltale signs of planets passing in front of their stars. TESS finished its initially-planned survey in July 2020, but its mission has been extended into at least 2022. Since its launch, the telescope has allowed astronomers to pinpoint more than 2,000 exoplanet candidates.

In the midst of those discoveries lie the planets orbiting TOI 2076. In studying this object, a physics student at Loughborough University in England named Alex Hughes noticed a blip in the data. And when astronomers took a closer look, they found three planets with sizes somewhere between that of Earth and Neptune.

TOI 1807, on the other hand, only has one planet, which is around twice Earth's size. This planet orbits its sun at a curiously close distance and astronomers think that a year there could last as little as 13 Earth hours. Planets don't typically form that close to their stars, and the question of how TOI 1807’s planet got there has piqued astronomers' curiosity.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Both stars are around 200 million years old, less than one-twentieth the current age of our own solar system. Their planets have "grown up" from lumps of gas and dust and primordial rock and are now preparing to enter their billions-year long adulthood. That also means these planets are an exciting opportunity to observe planets as they come of age, and there's a lot that astronomers don't know. For instance, we don't know how their atmospheres might form, or how TOI 1807 might have gotten there.

So the astronomers behind the discovery plan to look more closely. Their next goal: determining the planets' masses.

"If you want to see how planets evolve, your best bet is to find many planets of different ages and then ask how they're different," Trevor David, a research fellow at the Flatiron Institute's Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York, said in a statement. "The TESS discovery of the TOI 2076 and TOI 1807 systems advances our understanding of the teenage exoplanet stage."

This work was described in a study published July 12 in the Astronomical Journal.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Rahul Rao is a graduate of New York University's SHERP and a freelance science writer, regularly covering physics, space, and infrastructure. His work has appeared in Gizmodo, Popular Science, Inverse, IEEE Spectrum, and Continuum. He enjoys riding trains for fun, and he has seen every surviving episode of Doctor Who. He holds a masters degree in science writing from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program (SHERP) and earned a bachelors degree from Vanderbilt University, where he studied English and physics.