Book excerpt: 'The Smallest Lights in the Universe'

Science, even science about the heavens, is done by people, astronomer Sara Seager reminds us throughout her new memoir, "The Smallest Lights in the Universe" (Crown, 2020).

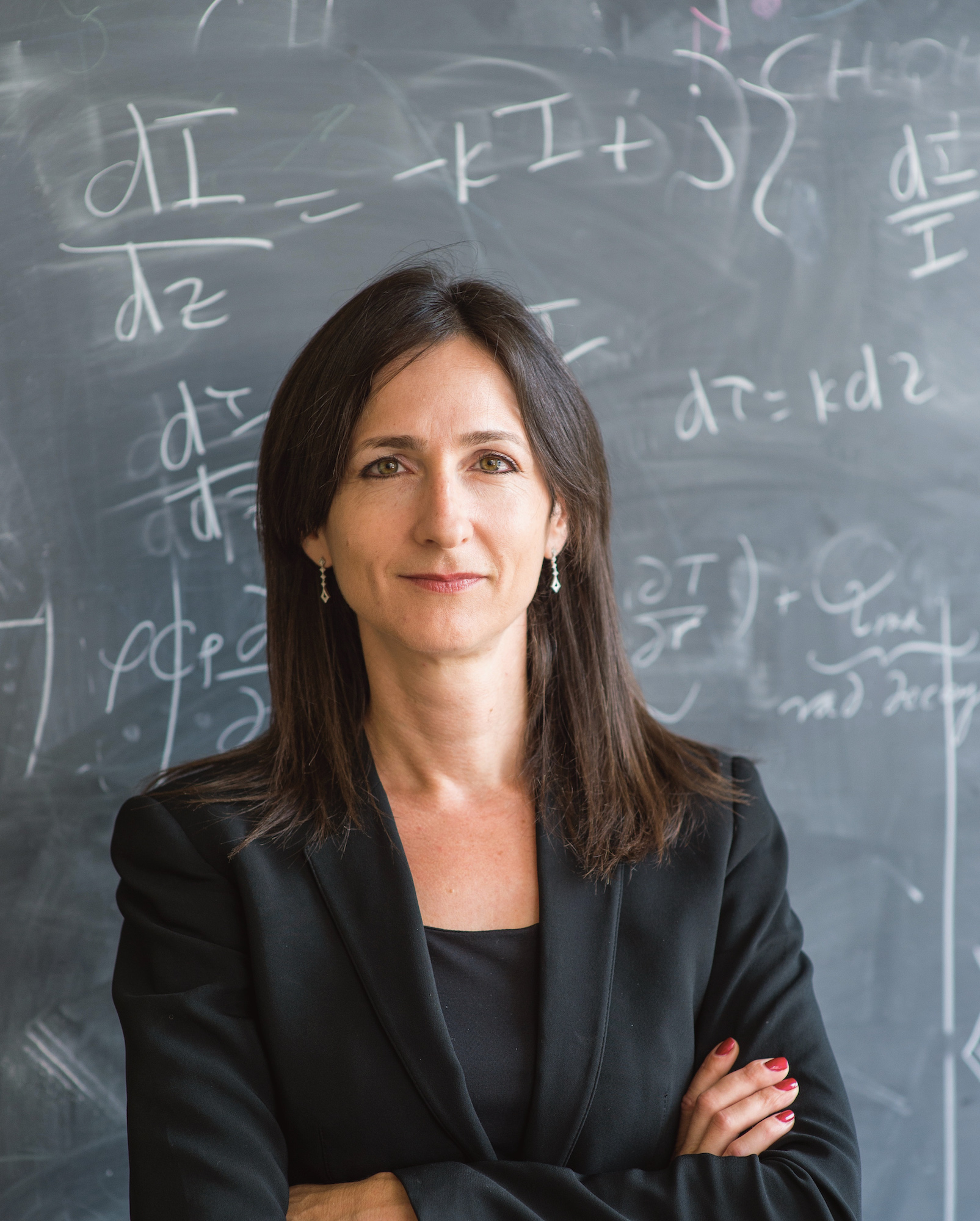

For Seager, a renowned astronomer and planetary scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, doing science means searching for another Earth around a distant star. But being human means enduring a difficult childhood, exploring northern Canada, raising two sons, losing her husband to cancer, then falling in love anew. Her grace joining the personal and the scientific begins with the book itself, as you'll read in the prologue below.

(Read an interview with Sara Seager about the book.)

Related: Best space and sci-fi books for 2020

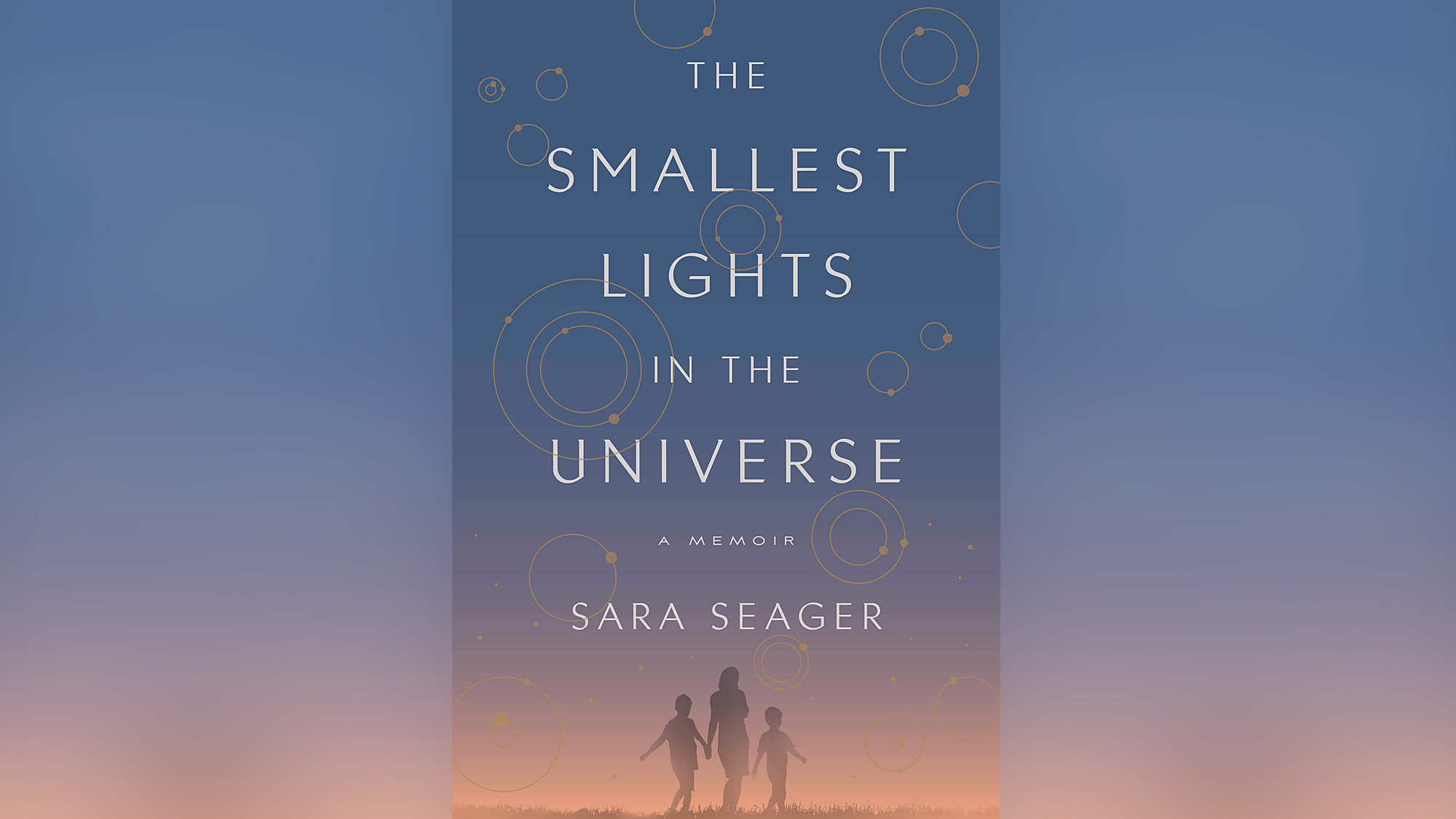

The Smallest Lights in the Universe: A Memoir

Crown, 2020 | $25.20 on Amazon

In this luminous memoir, an MIT astrophysicist must reinvent herself in the wake of tragedy and discovers the power of connection on this planet, even as she searches our galaxy for another Earth.

Prologue

Not every planet has a star. Some aren't part of a solar system. They are alone. We call them rogue planets.

Because rogue planets aren't the subjects of stars, they aren't anchored in space. They don't orbit. Rogue planets wander, drifting in the current of an endless ocean. They have neither the light nor the heat that stars provide. We know of one rogue planet, PSO J318.5-22 — right now, it's up there, it's out there — lurching across the galaxy like a rudderless ship, wrapped in perpetual darkness. Its surface is swept by constant storms. It likely rains on PSO J318.5-22, but it wouldn't rain water there. Its black skies would more likely unleash bands of molten iron.

It can be hard to picture, a planet where it rains liquid metal in the dark, but rogue planets aren't science fiction. We haven't imagined them or dreamed them. Astrophysicists like me have found them. They are real places on our celestial maps. There might be thousands of billions of more conventional exoplanets — planets that orbit stars other than the sun — in the Milky Way alone, circling our galaxy's hundreds of billions of stars. But amidst that nearly infinite, perfect in the emptiness between countless pushes and pulls, there are also the lost ones: rogue planets. PSO J318.5-22 is as real as Earth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There were days when I woke up and couldn't see much difference between there and here.

***

One morning it was only the distant laughter of my boys that persuaded me to push back the covers. Max was eight years old. Alex was six. They were looking out the window, their faces lit with kid joy. It was a blue-sky weekend in January, and a thin white blanket of snow had fallen overnight. Finally, a bright spot. We could go sledding, one of our family's favorite pastimes. After a quick breakfast, Max and Alex began putting on their snowsuits. With their plastic sleds stuffed into the car, we made the short drive to the top of Nashawtuc Hill.

The hill is a popular gathering spot in Concord, Massachusetts. It's steep and fast enough to thrill even grownups. It can get busy, but not that morning. There wasn't really enough snow to sled, and tall grass and weeds poked out of what snow was there. I tried to pretend for the sake of the boys that sledding would still be fun. I didn't believe it myself. I'd spent my entire life searching for lights in the dark; now I could see only the blackness that surrounded them. But we had gone to the trouble of getting to the top of the hill. The boys might as well try to get to the bottom.

There were two other women standing at the top, mothers talking and laughing with each other while their kids played. They were beautiful, their faces put together enough to make me resentful. I looked at them coldly. I thought: Who gets up on a Sunday morning and thinks to do their makeup like that? They looked like a picture from a brochure for happiness.

Max was big enough to get all the way down the hill. Even if he hit the weeds, he had enough mass and speed to pass over and through them. Physics weren't so much on Alex's side. He kept getting stuck. He tried going down a few times but eventually gave up. Seeing his brother hurtle to the bottom was too much for him to take. Alex sat there, pouting, right in the middle of the hill. He wasn't crying. He just spread himself across the hill and refused to move. If he wasn't going to have any fun, nobody was.

One of the women called over and asked if I could shift him. He was in the way, and she was afraid he was going to get hurt. I understood why he needed to be moved. I was also spent, my best plans undone. I wasn't in the mood to take orders from someone like her, from someone so pretty. I wasn't in the mood to take orders from anybody. I glared at her and shook my head.

She asked again.

"No," I said. "He has a problem."

She smiled and maybe even laughed a little. "Oh, okay," she said. "I mean, it's just that — "

I ignored her.

"It's just that the hill — "

"HE HAS A PROBLEM. MY HUSBAND DIED."

When you're in the ugly throes of grief, most people are repulsed by you. Nobody knows what to say or how to behave in your presence. Everybody's scared of what you represent, and in a way, I suppose, you learn to want them to be. The distance that people keep is a sign of respect: Your grief warrants a wide berth. You come to crave the ability to influence the movements of others, your sorrow a superpower, your sadness your most extraordinary trait. You come to crave the space.

I thought the woman on the hill would be shocked. I thought she would recoil. Instead, she did the strangest thing. She smiled, and then her eyes brightened. She became an oven, radiating warmth.

"Mine, too," she said.

I was stunned. I think I asked her how long she had been a widow. "Five years," she said. It had been only six months for me. She's forgotten what it's like, I thought. How dare she laugh at me.

I had an overwhelming urge to run, to return to my bed, lashed by my storms of molten iron, but Max was still having fun on the hill. It's moments like those, when you're torn in two, that you realize how alone you are. You need to find solutions to unsolvable problems. I decided that I'd take the boys home, and we'd get Alex the iPad. Then we'd come back. Alex could sit in the car and play, and Max could still sled. Hopefully the other widow would be gone by the time we got back.

She was still there when we returned. Meeting beautiful new people wasn't easy for me in the best of circumstances, and these were far from ideal. I had no idea what to do next. I tried to stand far away from her, to become even more repellant than I already felt. It didn't work. She started walking toward me. I was mortified. Could she not read the sign that was around my neck? Did she not know to leave me alone? But this time she approached me a little differently. She was measured in her movements, as though she didn't want to scare me away. She was still smiling, just not as widely.

She held a piece of paper in her hand. She'd written down her name, Melissa, and her phone number. She said that there was a group of widows our age in Concord. She spoke of them as if they were some kind of macabre troupe of acrobats, as though their name should be capitalized: the Widows of Concord. She said that five of them had just met for the first time to help each other through their new realities, their new parts as the abandoned ones. I should join them when they met again, she said. Then she smiled her warm smile and went back to her friend.

I would make six. I stood at the top of that hill and did the probability math. So many young widows in such a small town — Concord's population isn't twenty thousand — seemed highly unlikely. I had announced as much: "That's a statistical impossibility," I'd told Melissa. Then I remembered the previous summer, when I'd called Max and Alex's camp to warn the director that their father was dying. The director said that it wouldn't be a problem. "We're used to it," he said. I was taken aback at the time, but now I understood. Concord had more than its share of fatherless children, gone halfway to rogue.

I kept Melissa's number in my coat pocket. I would pull it out and look at it day after day, making sure it was real. I was terrified that I would lose it, but I was also too scared to call. I'd never met anybody quite like me; why should I now, after I'd become even more of an outlier? I didn't want to find out that the other widows weren't like me after all. Months before, I had called a number I'd seen in the local newspaper, advertising a widows' group, but the woman who picked up the phone had rejected me, saying that the group was for old widows, not young ones. She'd made me feel like a freak. In the middle of such sadness, it's hard to imagine that anyone in the world knows how you feel. And yet somehow there was a small army of women in my little town who knew exactly what I was experiencing, because they were experiencing it, too. Whenever I pulled out that that scrap of paper, I felt as though I were holding the last unstruck match in a storm.

It was nearly a week before I got the courage to call Melissa. The paper was nearly worn through by then.

The phone rang. Melissa picked up. She asked me how I was doing. Hardly anybody was brave enough to ask me that anymore, and I didn't know how to answer.

"Okay," I said. "Not okay."

Melissa said that the Widows of Concord were going to have a party soon. She asked if I wanted to come.

"Yes," I said. "Very much. When are you getting together?"

There was a little pause.

"Valentine's Day."

Reprinted from THE SMALLEST LIGHTS IN THE UNIVERSE Copyright © 2020 by Sara Seager. Published by Crown, an imprint of the Random House Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, on August 18.

You can buy "The Smallest Lights in the Universe" from Amazon or Bookshop.org.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Professor Sara Seager is an astrophysicist and a Professor of Physics, Professor of Planetary Science, and a Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology where she holds the Class of 1941 Professor Chair. She has been a pioneer in the vast and unknown world of exoplanets, planets that orbit stars other than the sun. Her ground-breaking research ranges from the detection of exoplanet atmospheres to innovative theories about life on other worlds to development of novel space mission concepts.

In space missions for planetary discovery and exploration, she was the Deputy Science Director of the MIT-led NASA Explorer-class mission TESS; she was PI of the JPL-MIT CubeSat ASTERIA; is a lead of the Starshade Rendezvous Mission (a space-based direct imaging exoplanet discovery concept under technology development) to find a true Earth analog orbiting a Sun-like star; and most recently has directed a mission concept study to find signs of life or life itself in the Venus atmosphere and is PI of a small mission to Venus targeted for launch in 2023.

Her research earned her a MacArthur “genius” grant and other accolades including: membership in the US National Academy of Sciences; the Sackler Prize in the Physical Sciences, the Magellanic Premium Medal; and has been awarded one of Canada’s highest civilian honors, appointment as an Officer of the Order of Canada. Professor Seager is the author of, “The Smallest Lights in the Universe: A Memoir”.