NASA finds key molecules for life in OSIRIS-REx asteroid samples. Here's what that means

"For me, the question is: Why didn't life form on Bennu?"

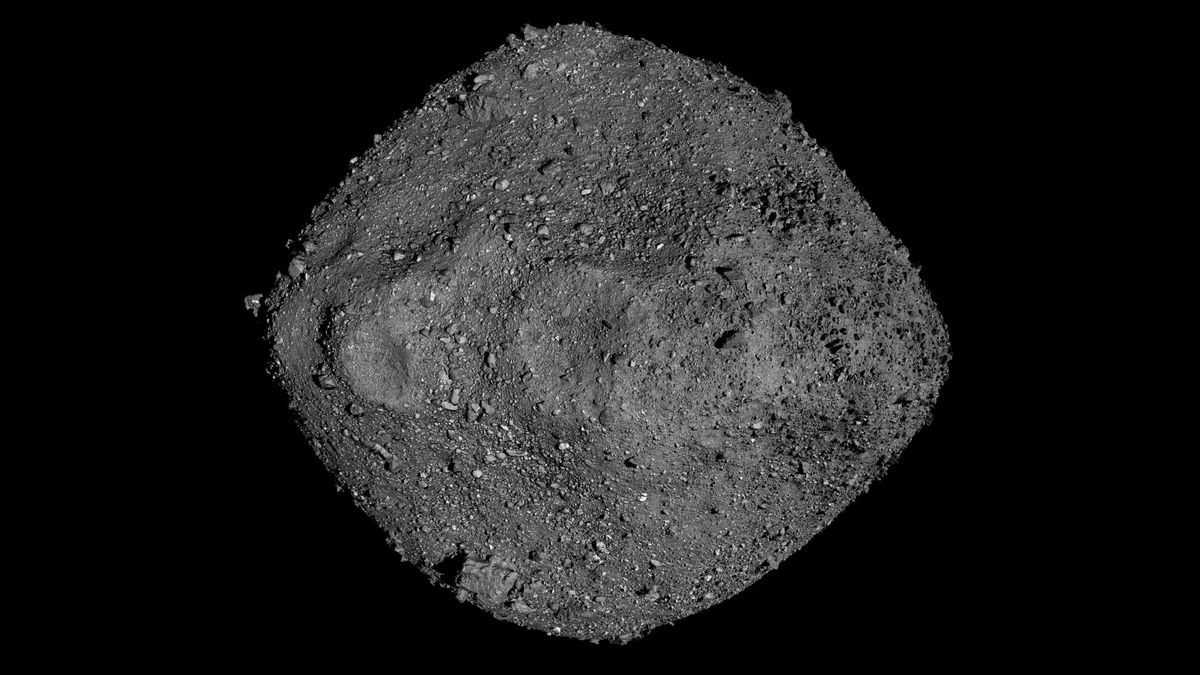

There are 20 amino acids that create the proteins required for life on our planet — and scientists have now found exactly 14 of them on an asteroid millions of miles away. The asteroid in question, named Bennu, was the focus of a very dreamy NASA mission called OSIRIS-REx that launched in 2016.

The first goal of OSIRIS-REx was to blast a spacecraft toward the grayish, lumpy object and get it really close to the surface so the probe could pluck up some space rock samples with a robotic arm. The second goal was to seal those samples within the craft for the long journey back to Earth in order to safely bring them down through our planet's atmosphere. In other words, OSIRIS-REx was meant to deliver untouched asteroid chunks home to be analyzed in a lab. This brilliant plan worked. The samples landed in the Utah desert in 2023, and scientists have been wringing those priceless pieces of Bennu for data ever since.

So far, they've managed to reveal things like the fact that asteroid Bennu — a space rock representative of the early solar system — appears to hold compounds containing water and carbon. However, that was more or less expected (or at least actively hoped for as corroborative evidence of scientists' Bennu theories). The team's latest discoveries, which NASA unveiled on Wednesday (Jan. 29), come as a bit of a surprise, and pose many exciting questions. The most notable parts are probably that researchers found those aforementioned 14 amino acids, a high concentration of ammonia, and the five nucleobases life on Earth uses to transmit genetic instructions within DNA and RNA.

"For me, the question is: Why didn't life form on Bennu?"

Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters, Washington

"Their findings do not show evidence of life itself, but they do suggest that the conditions necessary for the emergence of life were likely widespread across the early solar system," Nicky Fox, associate administrator, Science Mission Directorate, NASA Headquarters, Washington, told reporters during a Jan. 29 press conference. "This, of course, increases the odds that life could have formed on other planets."

Forbidden broth

There were several other reveals about the Bennu samples during this press conference, and it's notable that pretty much all of them suggest the asteroid had the right ingredients for life as we know it. This seems to provoke a big question for scientists: Why didn't life form on Bennu?

"This is a future area of study for astrobiologists from around the world to ponder," said Jason Dworkin, OSIRIS-REx's project scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. "Looking at Bennu as an example of a place that had all the stuff, but didn't make life — why was Earth special?"

For instance, scientists identified evidence of a salty brine, or "broth," with traces of 11 minerals rich in sodium carbonate, phosphate, sulfate, chloride and fluoride.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We see this huge range of salts," said Sara Russell, a cosmic mineralogist at the Natural History Museum in London. "We believe we're finding the story where, together, the water, the organic material, and all of these bioessential elements could have been delivered on asteroids like Bennu in the early solar system, to the Earth and to other planets as well, to enable them to be seeded with all the ingredients they needed to kickstart life."

The team also specifically found ammonia — a lot of ammonia — in the Bennu samples. They found about 230 parts per million of it, which Danny Glavin, senior scientist for sample return at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland, puts into perspective as about 100 times more than natural levels of ammonia in the soils on Earth.

"Ammonia is, of course, essential for many biological processes," Glavin said. "It was likely a key chemical building block through the formation of amino acids and nucleobases and, again, the genetic components of DNA and RNA."

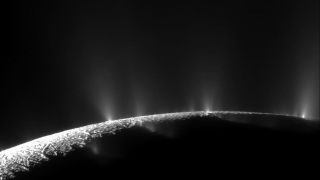

The OSIRIS-REx team says this suggests Bennu — or at least the parent asteroid from which Bennu is believed to have broken off — must have once existed in the colder, outer regions of space because ammonia is a volatile substance. For ammonia to exist in salt form, the environment must be cold. As such, scientists have also previously found evidence for ammonia in salt form on the dwarf planet Ceres, which sits in the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, and within the plumes of Saturn's famously icy moon Enceladus. Over the years, Enceladus has gained much-deserved attention in the quest to find life beyond Earth.

Perhaps Fox summed it up best: "The OSIRIS REx team discovered that Bennu contains many precursor building blocks of life, along with the evidence that it comes from an ancient wet world and contains materials that point to Bennu having traveled from the coldest regions of the solar system that are likely beyond Saturn's orbit."

A hypothesis, thwarted

In a separate train of thought — and my personal favorite Bennu discovery so far — the OSIRIS-REx sample analysis also communicated something peculiar about the "chirality" of molecules found in the Bennu samples. A chemistry term, chirality basically refers to the orientation of a molecule. A molecule is considered "chiral" if it can't be superimposed on a mirror image of itself no matter what you try to do. This means that there must be two versions of that molecule, a left-handed version and a right-handed version. (Think about your own left and right hands. If your palms are facing upward, they follow this principle, too).

"All life on Earth is based on the left-handed form," Glavin said. "And this is a big mystery, actually … we don't know how this happened."

As Glavin explains, scientists have been studying meteorites for decades, checking space molecule handedness to compare that with our Earth molecule handedness — and they consistently seem to find that meteorites, especially with similar compositions to Bennu, exhibit predominantly left-handed molecules. But meteorites don't get the princess treatment that Bennu samples did. They're, more or less, contaminated by all the stuff they pass through before hitting our planet.

"The hypothesis had been that the early solar system was biased towards the left-handed version, very early on, prior to the origin of life," Glavin said. "So we were looking forward to studying these better samples, hopefully confirming that hypothesis."

But Bennu bucked the trend. The team found equal parts left-handedness and right-handedness in their OSIRIS-REx samples, referred to as a "racemic" mixture.

"I have to admit, I was a little disillusioned or disappointed," Glavin said. "I felt like this had invalidated 20 years of research in our lab and my career. But I mean, here's the thing: This is exactly why we explore. This is why we do these missions, right? If we knew everything in advance, we wouldn't need to do an OSIRIS REx to bring these samples back."

What's new and what's not

There are a few things worth noting when it comes to the novelty of OSIRIS-REx. First of all, this is not the first time scientists have brought space samples back to Earth for analysis — looking at you, Apollo moon rocks — and it's also not the first time asteroid samples in particular have landed on Earth with human intervention. In fact, it's not even the first time we've found these tantalizing building blocks of life on an asteroid at all.

OSIRIS-REx, however, does have its own reasons to boast.

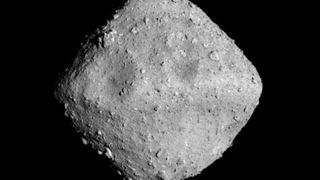

For instance, the first-ever space-rock-sample-return mission was performed by Japan's aerospace agency, JAXA, which delivered about 5 grams (0.2 ounces) of material from the asteroid Ryugu to Earth. OSIRIS-REx managed to bring back about 121 grams (4.3 ounces) . Five grams of asteroid bits were enough to yield some exciting results, though, which foreshadows what 121 grams of asteroid bits could lead to. That's especially considering how NASA aims to deep freeze some of those grams so future scientists, perhaps not yet born, can reap the benefits of OSIRIS-REx as well one day, with inevitably better technology and better context.

"The aim was to retrieve 60 grams of material — we got more than double that," Dworkin said. "And this sample exists for further and deeper studies."

Concerning the chemistry being discussed here, it's also true that the organics found on Bennu have been found on other meteorites before. Some of life's 20 amino acids have even been found in JAXA's samples of Ryugu. In fact, on the topic of Ryugu samples, scientists also found ammonia there (albeit not quite the heaping amounts they're seeing in Bennu samples) as well as trace minerals (though different types).

First off, in comparison to meteorites, which enter Earth's atmosphere while enduring a fiery reentry process before plummeting to the ground, the OSIRIS-REx samples are pristine due to the lengths NASA went to to utilize a spacecraft in their delivery. And, when it comes to Ryugu, I suppose it's always great to have double evidence for asteroid organics to begin with.

"The bottom line is we have a higher confidence that the organic material we're seeing in these samples are extraterrestrial and not contamination," Glavin said. "We can trust these results."

At the end of the day, the pristine quality of the Bennu samples — and the Ryugu samples, for that matter — may be why scientists were able to find these exciting space rock molecules at all.

"We've never seen minerals like this in meteorites before, and only recently have our colleagues working on samples from Ryugu, brought back by the Japanese Hayabusa2 mission, documented a different sodium carbonate mineral and magnesium sodium phosphate," Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, said. "But even though we've never seen these in meteorites, they're actually reasonably well known from Earth where sodium rich lakes like Searle lake in California and the Mojave, through evaporation, form sodium-rich brine, salt-rich layers."

As those layers evaporate, he said, they become increasingly concentrated in things like sodium and chlorine and fluorine. But, then, why wouldn't they be seen in the meteorites?

Well, seeing as how these minerals form from the evaporation of water, as with those lakes McCoy mentioned, any general contact with water would make them disappear. Earth's atmosphere has water content galore — and it is that same atmosphere that meteorites travel through when they fall from space. OSIRIS-REx's asteroid samples don't have this issue, as they remained sealed within their spacecraft upon returning to Earth, where they were immediately transferred to a highly controlled containment room.

That wasn't all. To further ensure accuracy, the team even examined residue that may have come from the spacecraft itself that could've altered the samples and data coming from them.

"I'd also like to mention that, and thank the Kennedy Space Center launch services, for helping us get samples of the hydrazine propellants used on the on the spacecraft to test and verify that the ammonia, produced by hydrazine propellants on the spacecraft, is chemically distinct from the ammonia we detect in the sample," Dworkin said.

So, at this point, what are we left with? Well, as is often the case in space exploration, higher data quality means clearer answers, and clearer answers tends to mean a bucket of extra questions.

"For me, the question is: Why didn't life form on Bennu?" Fox said. "What was it that caused life not to form on some of these other bodies?"

These results were published across two papers on Jan. 29, in the journals Nature and Nature Astronomy.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.

-

Broadlands There are good reasons why life didn't form. Peptide and nucleotide bonds need to form from amino acids before proteins can form. This means the input of energy with the release of water....alternations of heating snd cooling, wetting and drying for chain length extensions. All this in the presence of both infrared and UV radiation. On Earth this took place protected by ozone derived from oxygen produced by stratospheric UV photodissociation of water with the loss of light hydrogen to space. None of that could take place on an asteroid.Reply -

A J Foster Maybe we are not special. These building blocks are universal so that means life can form in other environments than ours. We can't expect duplicating results but why would we believe we were the only conscious intelligent beings?Reply -

Broadlands Reply

Ask yourself.. what are aliens made of if they are different from us and how long did it take their evolution to get it done if the environment was different?A J Foster said:Maybe we are not special. These building blocks are universal so that means life can form in other environments than ours. We can't expect duplicating results but why would we believe we were the only conscious intelligent beings? -

JPL_ACE Seems to me life needs more than what was on Benny. That is why none formed. My question is why did the parts we found exist? How did they get there?Reply