Black holes may obey the laws of physics after all, new theory suggests

"The singularity is the most mysterious and problematic part of a black hole. It's where our concepts of space and time literally no longer make sense."

A team of scientists has developed a recipe for black holes that eliminates one of the most troubling aspects of physics: the central singularity, the point at which all our theories, laws and models shatter.

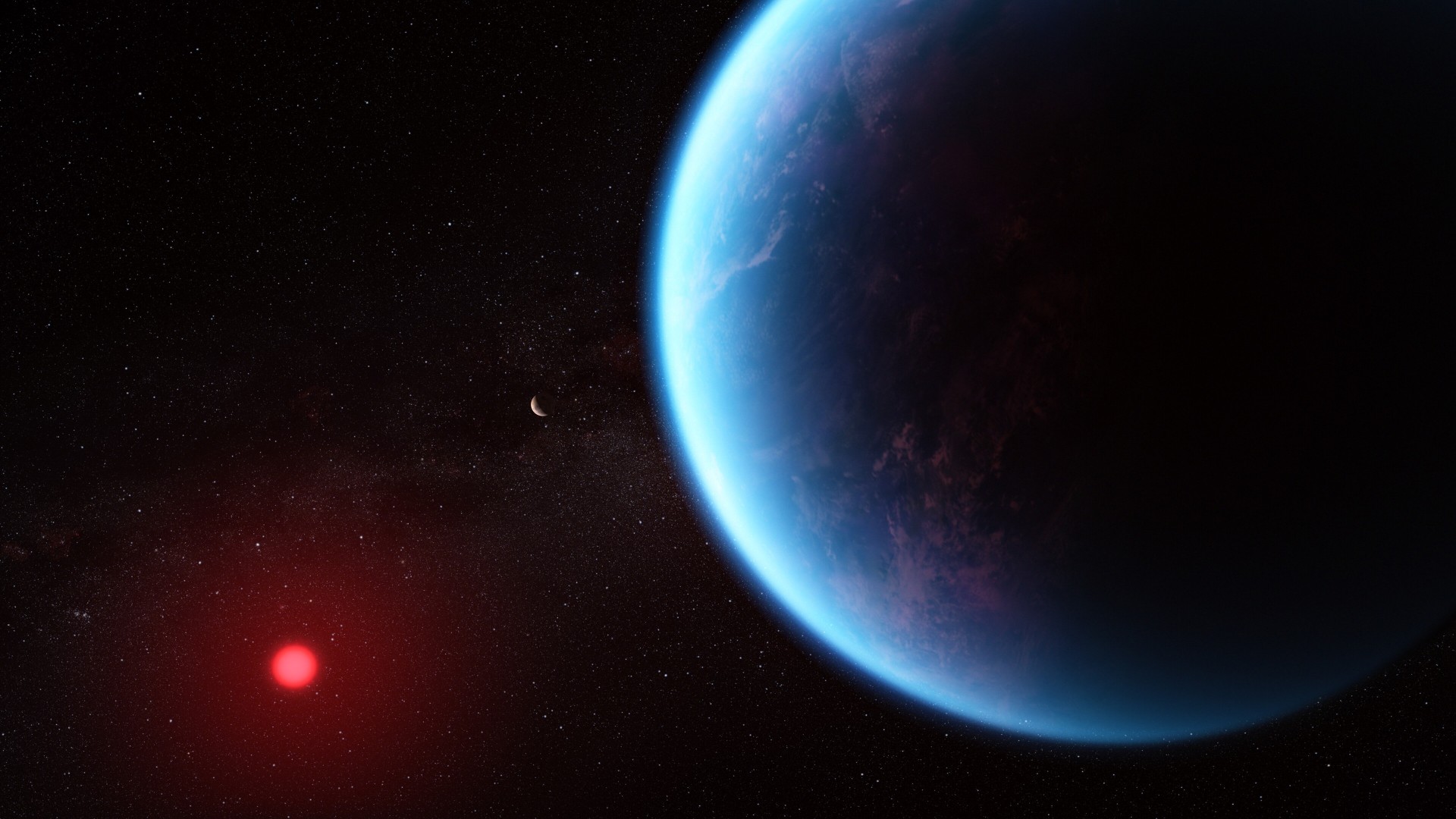

If you were going to design an object to preserve mystery while being utterly troubling, you couldn't do much better than a black hole.

First, the outer boundary of these cosmic titans is a one-way light-trapping surface called an event horizon, the point at which a black hole's gravity is so powerful that not even light can escape. This means no information can escape from within a black hole, so we can never directly observe or measure what lies at its heart.

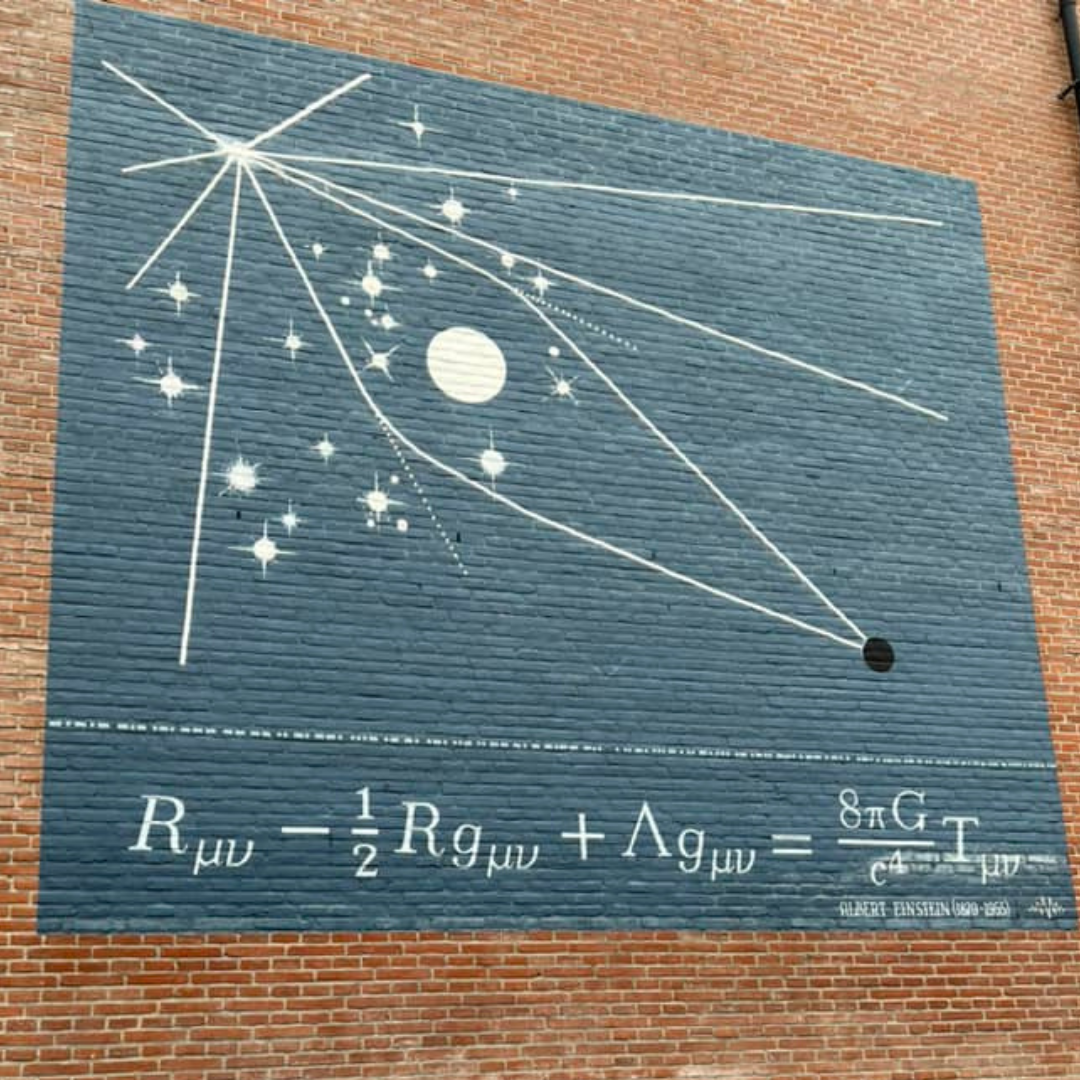

Using the mathematics of Einstein's 1915 theory of gravity, called general relativity, scientists can model the interior of a black hole. The problem is that, when they do this, general relativity tells us that all mathematical values go to infinity at the "singularity" at the heart of a black hole.

This new research suggests that "ordinary black holes" without a central singularity — the physics equivalent of having your cake and eating it — may be more than just the fever dream of hopeful physicists.

"The singularity is the most mysterious and problematic part of a black hole. It's where our concepts of space and time literally no longer make sense," study team member Robie Hennigar, a researcher at Durham University in England, told Space.com. "If black holes do not have singularities, then they are much more ordinary."

Related: Black holes: Everything you need to know

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Singularity-minded: Physicists want one thing

Einstein's theory of general relativity states that objects with mass curve the very fabric of space-time (the three dimensions of space united with the one dimension of time), and gravity arises from this curvature. The greater the mass, the more extreme the curvature of space-time, and the stronger the influence of gravity. All of this is calculated with the equations that underpin general relativity: Einstein's field equations.

"The way that the space-time curves is determined by the Einstein field equations, which are the cornerstone of general relativity," team member Pablo Antonio Cano Molina-Niñirola, of the Institute of Cosmos Sciences of the University of Barcelona (ICCUB) in Spain, told Space.com.

"These equations are extremely successful, as they predict a plethora of observable phenomena in the cosmos, from the motion of planets to the evolution of the universe and the existence of black holes," he added. "But they also predict the existence of singularities, and this is problematic."

Black holes — regions of space-time with extreme curvature — first arose as a concept from solutions to Einstein's field equations suggested by German physicist and astronomer Karl Schwartzchild as he served on the front line during the First World War in 1915. These solutions go to infinity at the center of that region. Physicists don't like infinities, as they indicate the breakdown or incompleteness of their models, or suggest something entirely unphysical. That means something really troubling and undesirable for physicists.

"In general relativity, the interior of a black hole is like a contracting universe, where the singularity represents the moment when space itself collapses," Molina-Niñirola said.

Molina-Niñirola added that many physicists believe that, when gravity becomes exceptionally strong and space-time is highly warped, general relativity must be replaced by a more fundamental theory. It has been presumed that this would be a theory of quantum gravity leading to a "theory of everything" that would unite the so-far incompatible theories of general relativity and quantum physics.

"The hope is that, in this complete theory, black hole singularities will be removed," Molina-Niñirola said. "Now, our recipe for regular black holes goes precisely in this direction, but instead of using a complete theory of quantum gravity, we use something called an 'effective theory.' This is a classical theory of gravity that is supposed to capture the effects of an assumed theory of quantum gravity."

This amounts to the team modifying the Einstein field equations so that gravity behaves differently when space-time is highly curved. Ultimately, this leads to the removal of black holes' central singularities.

Related: Albert Einstein: His life, theories and impact on science

Quantum gravity and other problems

This newly modified theory suggests there is no singularity at the heart of a black hole. So what does exist in this extreme, exotic realm?

"In our model, the space-time collapse stops, and the singularity is replaced by a highly warped static region that lies at the core of the black hole," Molina-Niñirola said. "This region is static because it does not contract. That means an observer could hypothetically stay there, assuming they were able to survive the huge, but finite, gravitational forces in this region."

Apart from curved space-time, what else dwells at the heart of black holes, if this theory is correct? According to Hennigar, strictly speaking, nothing.

"These black holes are pure vacuum everywhere; there need not be matter present, but one can easily include it if desired," the University of Durham researcher continued. "It might sound weird to have a black hole in the absence of matter, but the same thing can happen even in general relativity."

Even if the team's black hole concept were verified, it likely wouldn't halt the search for a valid model of quantum gravity and a theory of everything.

"In some sense, this is a problem that cannot be avoided. Stars are collapsing all the time in our universe; it is an unavoidable physical process. But this commonplace occurrence is something that pushes us past everything we know," Hennigar continued. "In the final stages of collapse, just before one would reach the singularity, both gravity and quantum effects will be important.

"So we already know that the conclusions one would draw from general relativity alone are insufficient to describe such an extreme place/moment."

Does losing the singularity mean losing the mystery? Not quite...

If correct, this research may have somewhat demystified black holes, but it opens up many questions that will still have to be answered.

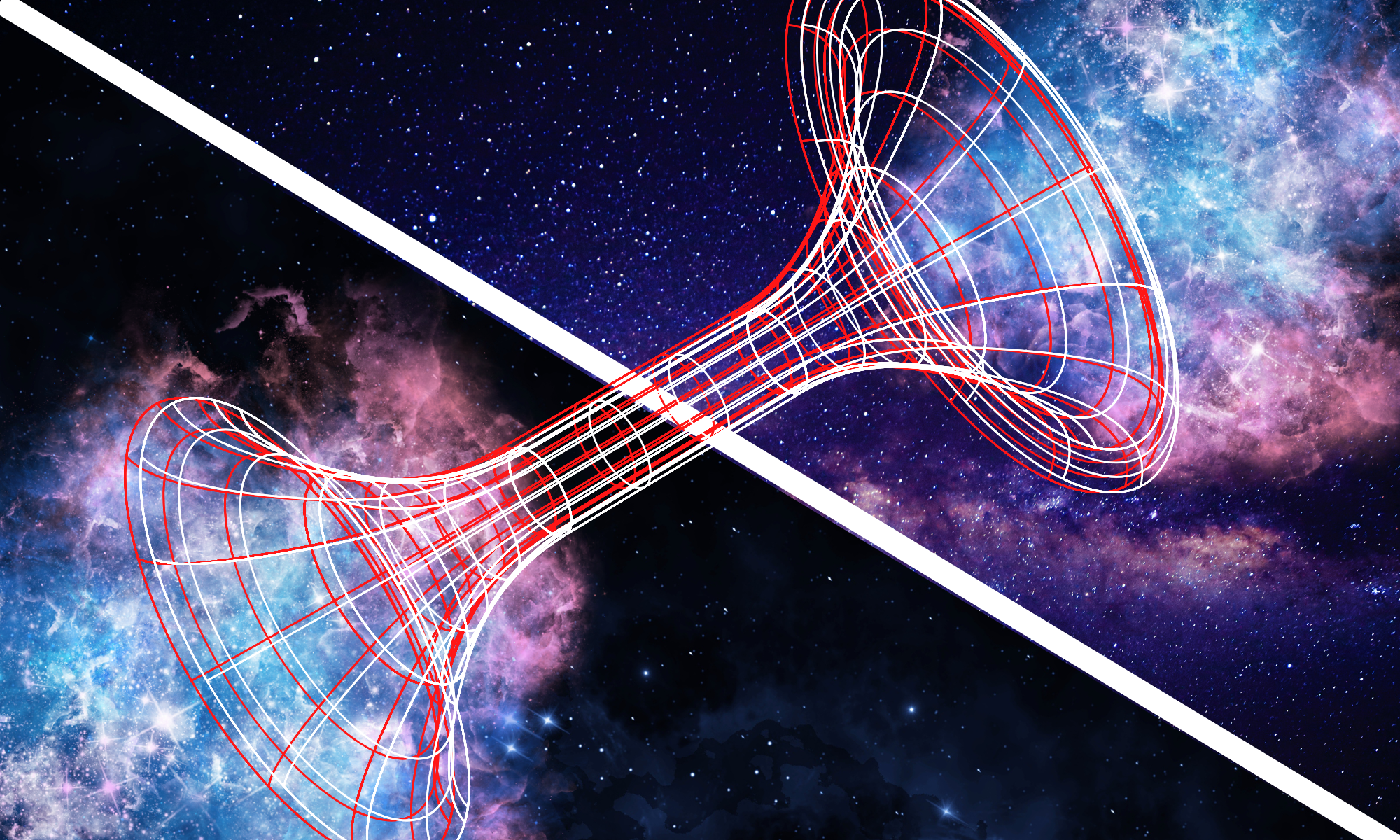

"Our work provides answers to some mysteries, but it opens others," Molina-Niñirola said. "For instance, according to our model — and other proposals in scientific literature — the matter that falls inside a regular black hole would ultimately exit the black hole through a white hole located in a different universe or in a disconnected region of the same universe.

"This looks very exotic, but it is the only possibility if singularities do not exist: all that goes into a black hole must eventually come out of it."

The researcher added that this process entails problems of its own, which must also be investigated to assess the robustness of the team's idea.

The big question is whether scientists could ever find evidence for this theory from actual observations of black holes; after all, we know we can't simply peer into their interiors.

"It’s difficult to say, since the effects that lead to singularity resolution might only become observable in regimes of extremely strong gravity, probably far stronger than what we can hope to observe," Molina-Niñirola said. "However, there are some experiments that can offer us some possibilities."

Molina-Niñirola explained that the observation of ripples in space-time called gravitational waves allows astronomers to observe much stronger gravitational fields than ever before. This gives scientists a unique chance at trying to spot effects beyond general relativity, including those that may lead to singularity resolution.

Additionally, if the team's theory is correct, there should be a tell-tale imprint in the very early universe, during the era of cosmic inflation right after the Big Bang.

"In this regard, the detection of a primordial, gravitational wave background — which has not been detected yet — could provide hints on possible modifications of gravity," Molina-Niñirola said. "Finally, a consequence of the absence of singularities is that the end-product of black hole evaporation via Hawking radiation would be a microscopic black hole.

"These microscopic black holes provide a possible dark matter candidate. Thus, if dark matter turned out to be composed of tiny black holes, this would be an indirect proof in favor of the absence of singularities."

The team's research was published in the journal Physics Letters B in February 2025.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.