NASA spacecraft spots monster black hole bursting with X-rays 'releasing a hundred times more energy than we have seen elsewhere'

"This pushes our models to their limits and challenges our existing ideas about how these X-ray flashes are being generated."

We've all woken up in a terrible mood from time to time, but a newly observed monster black hole is really having a bad day.

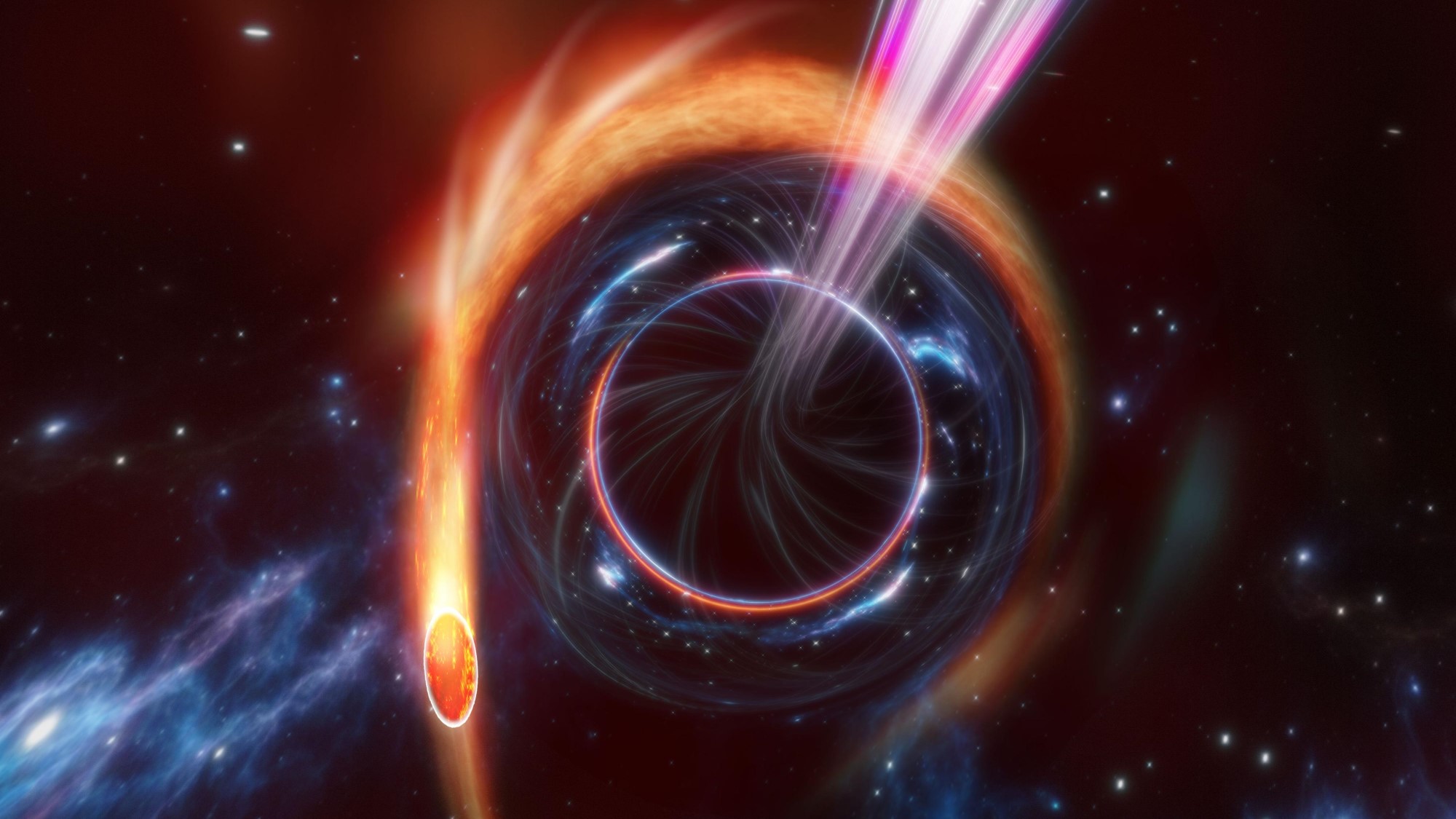

The previously inactive supermassive black hole at the heart of the galaxy SDSS1335+0728, located about 300 million light-years away from us, was seen erupting with the longest and most powerful X-ray blasts ever seen from such a cosmic titan.

This active phase marks the start of the supermassive black hole devouring matter around it and erupting with short-lived flaring events called quasiperiodic eruptions (QPEs).

The black hole, which has remained quiet for decades, is responsible for a region at the heart of its galaxy called an "active galactic nucleus," or "AGN." The team has dubbed this AGN "Ansky."

The awakening of Ansky was first detected in late 2019, alerting astronomers who followed up on its manifestation with NASA's Swift X-ray space telescope. By Feb. 2024, astronomers had begun to see the black hole powering Ansky erupting with flares at fairly regular intervals. This offered a unique opportunity: It became possible to monitor a feasting and erupting supermassive black hole in real time.

"The bursts of X-rays from Ansky are ten times longer and ten times more luminous than what we see from a typical QPE," team member Joheen Chakraborty of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) said in a statement. "Each of these eruptions is releasing a hundred times more energy than we have seen elsewhere. Ansky's eruptions also show the longest cadence ever observed, of about 4.5 days.

"This pushes our models to their limits and challenges our existing ideas about how these X-ray flashes are being generated.”

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team's QPE observations were made possible with assistance from the European Space Agency (ESA) space mission XMM-Newton, NASA's NICE and Chandra missions, and archival data from eROSITA.

The team remains puzzled about the cause of Ansky's outbursts. QPEs have previously been associated with supermassive black holes capturing stars, ripping them apart, and devouring the remains. That stellar destruction doesn't seem to be happening for Ansky.

"For QPEs, we're still at the point where we have more models than data, and we need more observations to understand what's happening," ESA Research Fellow and X-ray astronomer, Erwan Quintin, said in the statement. "We thought that QPEs were the result of small celestial objects being captured by much larger ones and spiraling down towards them.

"Ansky's eruptions seem to be telling us a different story."

"These repetitive bursts are also likely associated with gravitational waves that ESA's future mission LISA (Laser Interferometer Space Antenna) might be able to catch," Quintin added, referring to the joint ESA/NASA space-based gravitational wave detector set to launch in 2037. "It's crucial to have these X-ray observations that will complement the gravitational wave data and help us solve the puzzling behaviour of massive black holes."

The team's research was published on Friday (March 11) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.