Surprised Russian school kids discover Arctic island has vanished after comparing satellite images

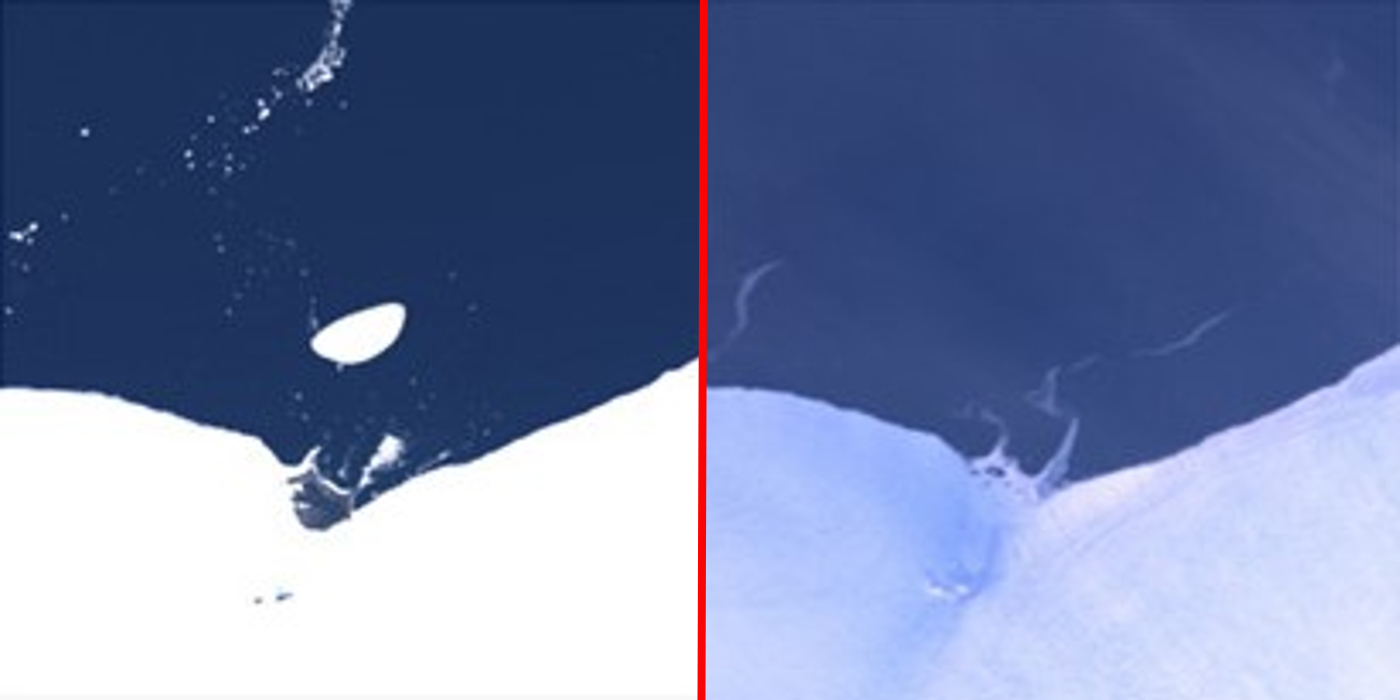

A student-led project comparing satellite images of the Arctic has discovered that a small Russian island has recently vanished after "completely melting" away.

A group of school kids and college students discovered that a Russian island in the Arctic has recently vanished after comparing satellite images of the area for an educational project.

Mesyatsev Island was a slab of ice and grit located just off the coast of the larger Eva-Liv Island in Franz Josef Land — a Russian archipelago of more than 190 islands in the Arctic Ocean. The smaller island, which was essentially just an iceberg, used to be an icy cape attached to its larger neighbor, but it likely broke away at some point before 1985, according to a 2019 study published in Geosciences.

In 2010, Mesyatsev Island had a surface area of around 11.8 million square feet (1.1 million square meters) — or the size of around 20 American Football fields. However, when the group of youngsters assessed new satellite photos of the island taken on Aug. 12 this year, they found that the island had an area of just 323,000 square feet (30,000 square m), which was more than 99.7% less than 14 years ago. By Sept. 3, newer images revealed that the island had completely vanished, according to a statement by the Russian Geographical Society that was translated into English. The students were comparing the satellite photos as part of the RISKSAT project run by the Moscow Aviation Institute.

The likely cause of the island's disappearance is rising temperatures caused by human-caused climate change, Alexey Kucheiko, a researcher at the Moscow Aviation Institute who coordinated the RISKSAT project, said in the statement. "The island has completely melted," he said.

Related: US Space Force satellite data shines light on mystery of Arctic warming

Mesyatsev Island had been melting ever since it broke away from Eva-Liv Island, but the rate at which it disappeared ramped up over the last decade. By 2015, the island measured around 5.7 million square feet (530,000 square meters) — less than half its total in 2010. And by 2022, it had become so small that researchers stopped monitoring it because they thought it would imminently disappear.

It was a surprise, therefore, that what was left of the island was still initially visible in the satellite images first observed by the students in August this year.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Researchers had initially abandoned tracking Mesyatsev Island because of a sharp increase in its rate of melting, which was triggered by a darkening of the island's icy surface in 2021. This darkening was likely the result of a layer of dust that had either blown onto the island or been released from the melting ice. This caused the ice to start absorbing more solar radiation, according to the Russian Geographical Society.

Researchers are unsure why the island has persisted longer than expected. However, experts previously theorized that the island's dusty layer could be removed by waves or rainwater, which could explain why it stopped melting so quickly.

Back when Mesyatsev Island was still attached to Eva-Liv Island, it was an important nesting site for walruses. However, the animals had to find a new place to meet up during the breeding season once the ice mass broke away, Yevgeny Yermolov, head of the historical and cultural heritage preservation department of the Russian Arctic National Park, told the state-run news site TASS.

Experts believe that the former Mesyatsev cape was left behind by a glacier that covered most of Eva-Live Island in the past, potentially when the larger island was still attached to another landmass, Yermolov added.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized. When not at work he can be found watching sci-fi films, playing old Pokemon games or running (probably slower than he'd like).

-

Unclear Engineer Editors: This article has the subheading reading:Reply

"The cryovolcanic "centaur" comet 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann has erupted four times in less than 48 hours, becoming unusually bright in the process. It is the most powerful outburst from the city-size oddball in more than three years."

That has absolutely nothing to do with the headline nor the text of the article.