Cosmic 'tornadoes' rage around the heart of the Milky Way and its supermassive black hole

"Unlike any objects we know, these filaments really surprised us. Since then, we have been pondering what they are."

Astronomers have discovered "space tornadoes" raging through the heart of the Milky Way in the vicinity of our galaxy's central supermassive black hole, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). The discovery provided the team with a more complete view of the cycle of creation and destruction at the heart of our galaxy.

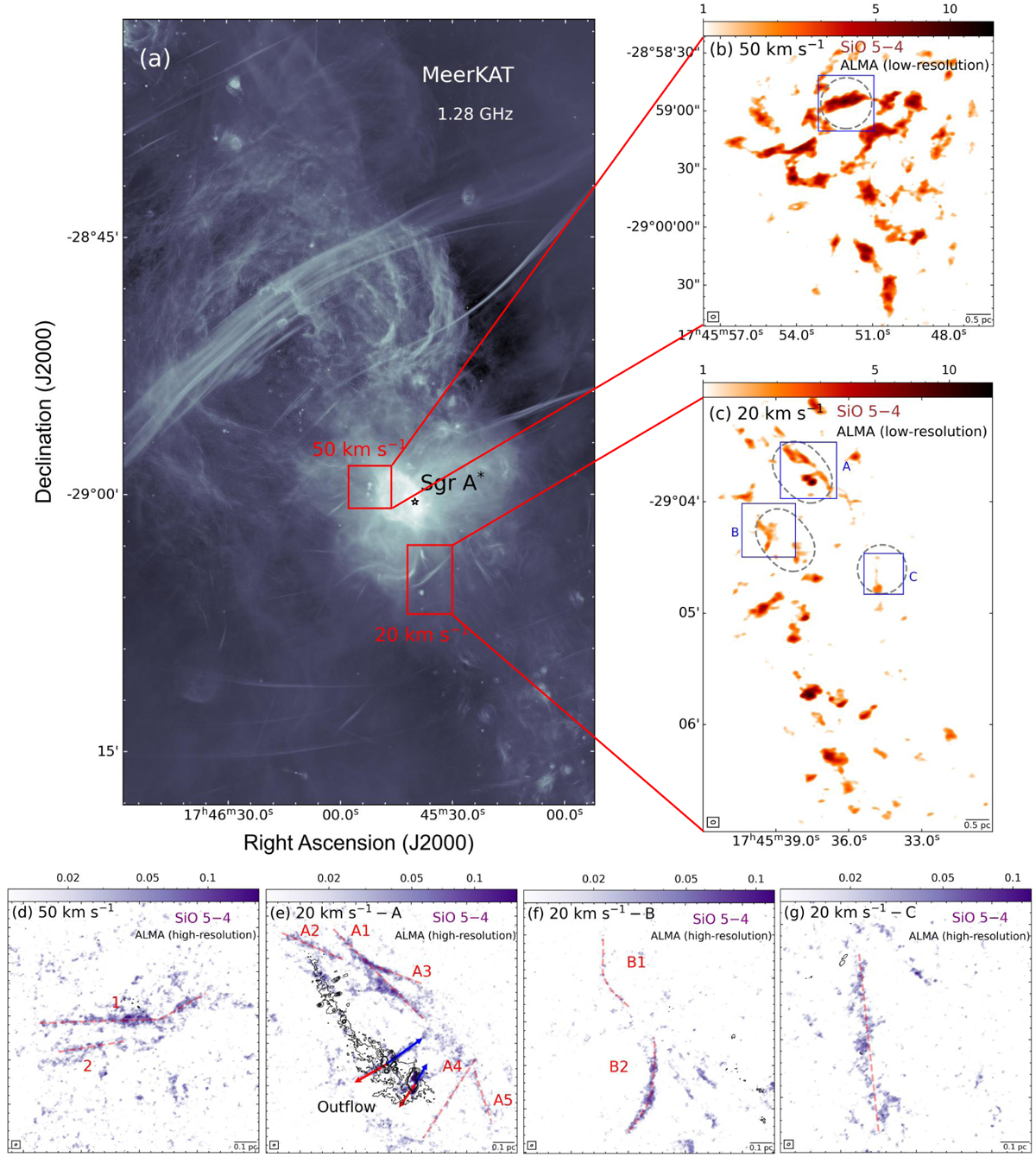

The researchers made the discovery using a network of radio telescopes in Chile called the Atacama Large Millimeter/ submillimeter Array (ALMA), which sharpened our view of motion within Milky Way region called the central molecular zone (CMZ) by a factor of 100.

"Our research contributes to the fascinating Galactic Center landscape by uncovering these slim filaments as an important part of material circulation," team member Xing Lu of the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory said in a statement.. "We can envision these as space tornados: they are violent streams of gas, they dissipate shortly and they distribute materials into the environment efficiently."

The CMZ has long been understood to house churning clouds of dust and molecules that are constantly undergoing a cycle of creation and destruction. However, the mechanism that drives this process has been shrouded in mystery.

"When we checked the ALMA images showing the outflows, we noticed these long and narrow filaments spatially offset from any star-forming regions," study team leader Kai Yang, of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, said in the same statement. "Unlike any objects we know, these filaments really surprised us. Since then, we have been pondering what they are."

Related: Facts about Sagittarius A*, the Milky Way's supermassive black hole

Mystery filaments wrap around the heart of our galaxy

The researchers used ALMA to track molecules, using them as "tracers" for various processes happening in the CMZ's molecular clouds. In particular, silicon monoxide proved useful in tracking energetic rippling shockwaves.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

This revealed details of the new type of long and narrow filamentary structures seen in the spectral lines of silicon monoxide and eight other molecules in the CMZ. These details were seen at a fine scale down to a resolution of around 0.033 light-years (0.01 parsecs). That's impressive, considering that Earth is around 27,800 light-years from the CMZ.

The fine structures stand out from other denser gas filaments of matter in the CMZ, as they don't appear to have velocities consistent with outflows of matter and they don't seem to be associated with dust emissions in the CMZ.

Furthermore, the newly discovered structures don't appear to be in hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning that the inward force of gravity acting upon them is not balanced by the outward pressure of the filaments' own gas and dust.

Related: Milky Way galaxy: Everything you need to know about our cosmic neighborhood

Astronomers don't currently know for sure how these thin filaments of dust and gas arise, but ALMA found hints that led them to strongly suspect that this process involves material being "shocked" — impacted by shockwaves.

These clues included the change in the energy levels of molecules of silicon monoxide due to rotation, known as "rotational transition," leading to an emission called SiO 5-4. Another clue was the abundance of organic molecules in this region seen by ALMA.

The team theorizes that shocks initially create these thin filaments in the process, releasing silicon monoxide and organic molecules like methanol, methyl cyanide, and cyanoacetylene into the interstellar medium. The filaments then dissipate, which renews the shock-released material in the CMZ.

The molecules then freeze, forming dust grains and thus establishing a balance between depletion and replenishment.

"ALMA’s high angular resolution and extraordinary sensitivity were essential to detect these molecular line emissions associated with the slim filaments and to confirm that there is no association between these structures and dust emissions," said team member Yichen Zhang of Shanghai Jiao Tong University. "Our discovery marks a significant advancement by detecting these filaments on a much finer 0.01-parsec scale to mark the working surface of these shocks."

If these fine filaments are abundant throughout the CMZ, as they are in the sample region ALMA found them in, this means there is a balance in the cycle of destruction and creation of molecules at the heart of the Milky Way.

“Silicon monoxide is currently the only molecule that exclusively traces shocks, and the SiO 5-4 rotational transition is only detectable in shocked regions with relatively high densities and temperatures,” Yang said. "This makes it a particularly valuable tool for tracing shock-induced processes in the dense regions of the CMZ."

The team hopes that future ALMA observations can cover more than just the SiO 5-4 transition of silicon monoxide in observations spanning a broader region of the CMZ.

Linking these observations up with simulations could confirm the origin of the slim filaments, thus better defining the cyclic processes within the extraordinary core region of the Milky Way.

The team's research was published in February in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.