Dark energy is even stranger than we thought, new 3D map of the universe suggests. 'What a time to be alive!' (video)

"The universe never ceases to amaze and surprise us."

New results from the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument (DESI) suggest that the unknown force accelerating the expansion of the universe isn't what we believed it to be. This hints that our best theory of the universe's evolution, the standard model of cosmology, could be wrong.

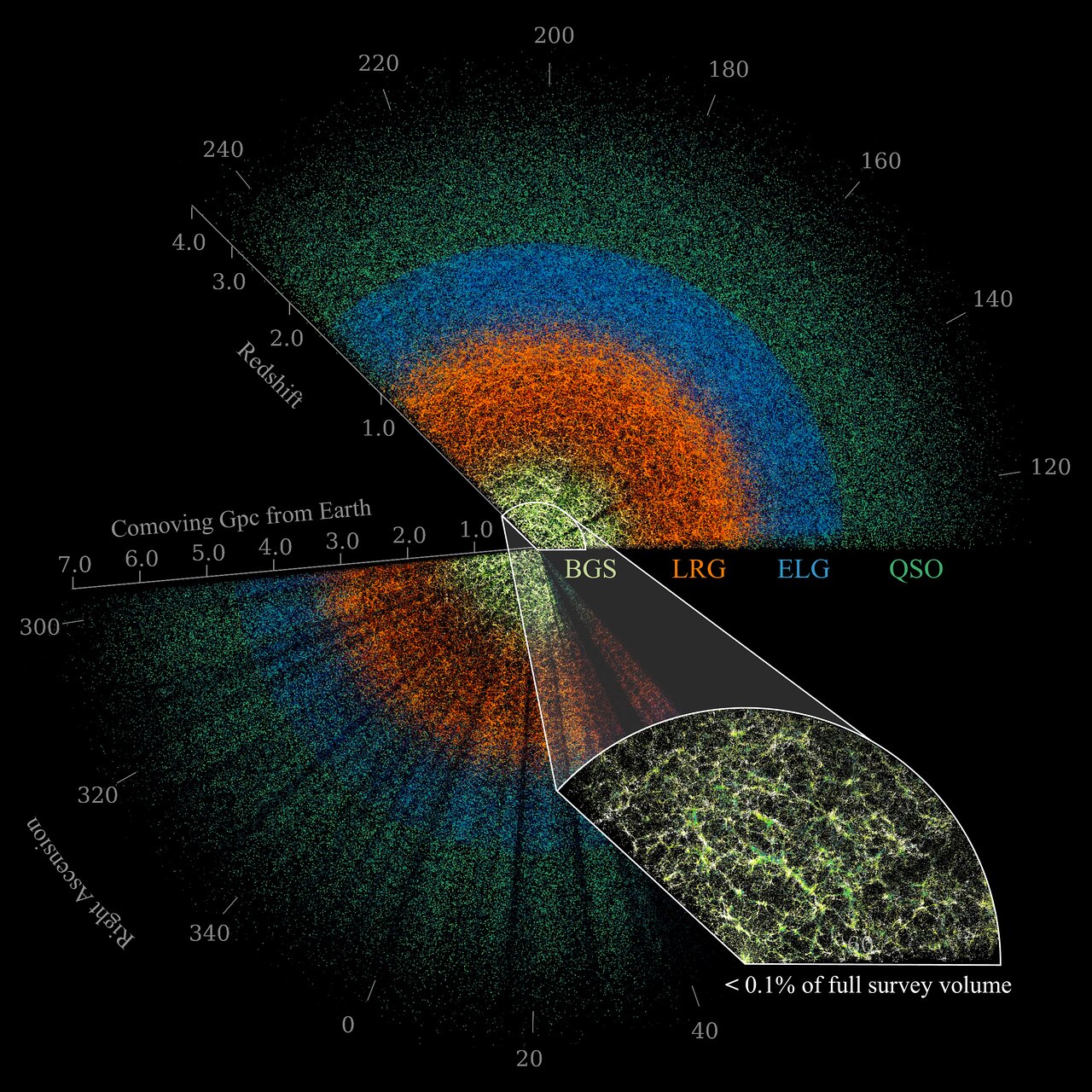

The newly released DESI data comes from its first three years of observations collected as the instrument, mounted on the Nicholas U. Mayall 4-meter Telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory, continues to build the largest 3D map of the universe ever created. By the time DESI completes its five-year mission next year, the instrument will have measured the light from an estimated 50 million galaxies and black hole-powered quasars, in addition to the starlight of over 10 million stars.

It is the capability of DESI to capture light from 5,000 galaxies simultaneously that makes it the ideal instrument to conduct a survey large enough to investigate the properties of dark energy. This new analysis focuses on data from the first three years of DESI observations, encompassing nearly 15 million of the best-measured galaxies and quasars.

"The universe never ceases to amaze and surprise us," DESI Project Scientist Arjun Dey said in a statement. "By revealing the evolving textures of the fabric of our universe as never before, DESI and the Mayall telescope are changing our very understanding of the future of our universe and nature itself."

DESI could change everything we know about dark energy

Dark energy is the placeholder name given to whatever aspect of the universe is causing the fabric of spacetime to inflate faster and faster, constantly pushing galaxies apart more rapidly.

It is thought to account for around 70% of the universe's matter and energy. The mysterious "stuff" called dark matter makes up another 25%, and ordinary matter comprising stars, planets, moons, our bodies and the cat next door accounts for just 5%. Essentially, everything we understand about the universe, including all of chemistry and biology is wrapped up in that 5%!

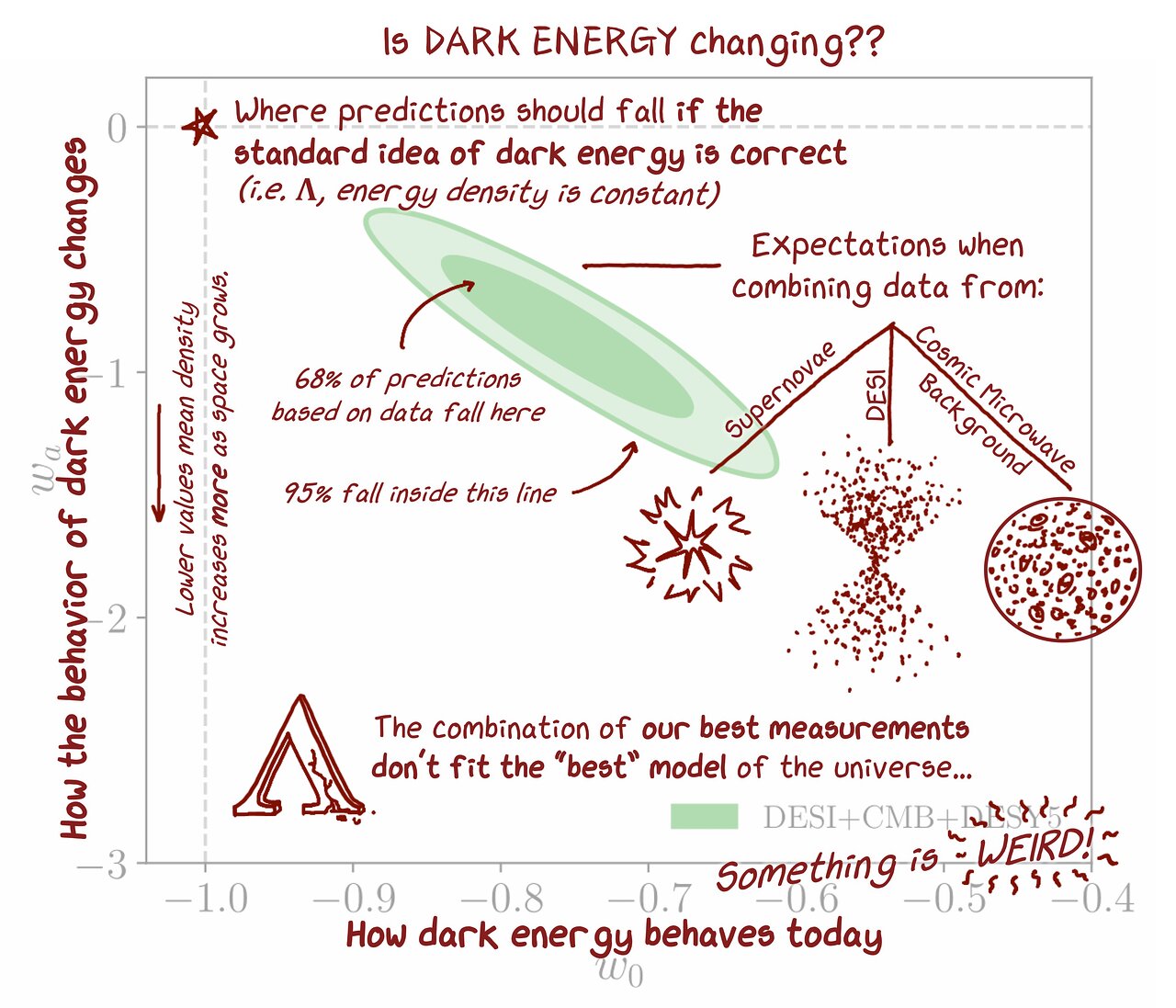

The current "best guess" at the identity of dark energy is the cosmological constant, the vacuum energy of energy space, which is baked into the pie we call the standard model of cosmology or the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LCDM) model. However, this model is built on the presumption that dark energy, represented by the Greek letter lambda (Λ), is constant over time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Vacuum energy describes the density of particles popping in and out of existence. While "something" appearing from "nothing" sounds crazy, you can think of it as the universe having an overdraft facility. Pairs of virtual particles are allow to "borrow" some energy from the cosmos to come into existence as long as they pay it back by meeting and annihilating each other.

When taken in isolation, the DESI findings don't actually challenge the picture of dark energy developed in the LCDM model. It is when the DESI data is compared with other measurements of the cosmos that problems with the cosmological constant start to manifest.

DESI is hinting, and not for the first time, that dark energy isn't constant but is changing over time. Specifically, this accelerating "push" seems to be weakening.

These measurements include our observations of a "fossil" light left over from an event that happened shortly after the Big Bang called the "last scattering," when the universe had expanded and cooled enough to allow electrons to bond with protons and form the first neutral atoms.

The disappearance of free electrons suddenly allowed photons, the particles that make up light, to travel freely. In other words, it was as if a universal fog had lifted, and the cosmos became transparent. This first light is referred to as the "cosmic microwave background" or "CMB," and it can still be observed today.

Tiny variations or "wrinkles" were "frozen into" the CMB by fluctuations in the density of matter in the early universe called baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO). As the cosmos continued to expand, so too did these wrinkles. Thus, BAO wrinkles can act as a standard measuring stick of the expansion of the universe, with their size varying at different cosmic times. This variation arises as a result of how fast the universe was expanding at those times.

Thus, measuring the BAO reveals the strength of dark energy throughout the history of the cosmos, and DESI can do this more precisely than any other instrument.

Changes in dark energy itself were also hinted at when DESI data was compared with observations of type Ia supernovas, cosmic explosions that occur when white dwarf stars "overfeed" on a companion star. This stolen material piles up on the surface of the stellar remnant until a thermonuclear runaway is triggered.

Type Ia supernovae are so uniform in terms of their light output that astronomers can use them as "standard candles" for measuring cosmic distances. In fact, type Ia supernovas were integral to the discovery that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, the genesis of dark energy, back in 1998.

These distance measurements are possible because of a phenomenon called "redshift," which occurs when the wavelength of traveling light is stretched as it crosses the expanding universe. The longer the light has traveled, the more extreme the shift toward the long wavelength "red end" of the electromagnetic spectrum. That means measuring the redshift of a very well-known and consistent source of light, a standard candle, can give distance measurements.

DESI data can also be combined with observations of an effect called "gravitational lensing," the distortion of light from distant galaxies by foreground objects of great mass to show the signature of evolving dark energy.

The evolution of dark energy isn't robust enough to be considered a "discovery" just yet, but different combinations of the data with other observations are pushing this concept toward what is considered the "gold standard" in physics for such a determination.

Astronomers prepare to dive into DESI data

In addition to unveiling these latest dark energy results on Wednesday (March 19), the DESI collaboration also announced that its Data Release 1 (DR1) is now available for anyone to explore through the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC).

DR1 contains information regarding 18.7 million cosmic objects, including roughly 4 million stars, 13.1 million galaxies, and 1.6 million quasars.

Luz Ángela García Peñaloza, a former DESI team member and a cosmologist at the Universidad ECCI in Colombia, is just one scientist who is thrilled with the new DESI results and the fact that DR1 is now available to the general astronomical community. told Space.com.

"I am also really excited to find out DESI has released redshift information of about 19 million galaxies and quasars. We've increased the number of identified galaxies by an order of magnitude in less than 10 years!" García Peñaloza said. "The most fascinating result of all is that different sets of observations, a combination of BAO from DESI with CMB data from Planck, and the three main sets of luminosity distances of type Ia supernovas are making a stronger case for an evolving dark energy model, disfavoring the cosmological constant.

"This is getting more and more consistent with other independent cosmological tests that seem to be opening a window of opportunity for new ways to explore and study dark energy and the accelerated expansion of the universe."

The availability of the DR1 data means astronomers outside the DESI collaboration can now dive into this vast dataset collected between May 2021 and June 2022.

"Our results are fertile ground for our theory colleagues as they look at new and existing models, and we're excited to see what they come up with," DESI director Michael Levi, a scientist at Berkeley Lab, said. "Whatever the nature of dark energy is, it will shape the future of our universe.

"It's pretty remarkable that we can look up at the sky with our telescopes and try to answer one of the biggest questions that humanity has ever asked.”

Meanwhile, the DESI collaboration is preparing to begin additional analyses of the new dataset to extract even more findings as DESI itself continues collecting data during its fourth year of operations.

"Just amazing," García Peñaloza concluded. "What a time to be alive and to be a cosmologist!"

The DESI data is discussed in a series of papers available here.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.