Euclid space telescope's 1st results reveal 'a goldmine of data' in search for dark matter and dark energy (images, video)

"Really, Euclid is not only a dark universe detective, it's also a time machine. We will look back 10 billion years in cosmic history."

The day that astronomers have been waiting for is here. On Wednesday (March 19), the European Space Agency (ESA) spacecraft Euclid released its first data to the public and to the scientific community.

This data includes three stunning previews of the deep-field space images that Euclid will produce. Within these deep fields are hundreds of thousands of galaxies of different shapes and sizes, revealing a tantalizing hint at the large-scale structure of the cosmos within the so-called "cosmic web." The data includes the classification survey of 380,000 galaxies, 500 new gravitational lens candidates, and a wealth of other cosmic bodies like galaxy clusters and active galactic nuclei.

Euclid must observe such a wide population of galaxies if scientists are to use its data to crack the mysteries of the "dark universe," the collective name for dark matter and dark energy. Euclid's potential to make a difference in this quest has led ESA scientists to dub the spacecraft their "dark universe detective." But this first data release shows that Euclid is capable of delivering so much more.

"I think the two biggest questions that we ask ourselves as humanity is, are we alone in the universe, and how does the universe work?" Carole Mundell, ESA director of science, said at a press conference held on Monday (March 17). "What are the fundamental laws of physics?"

Mundell added that as our understanding of the universe has developed over many years, we have come to understand that the "ordinary matter" that composes stars, planets, moons, asteroids, our bodies, and everything we see around us composes only 5% of the universe's total matter and energy.

"The other 95% is dark and is unknown," she continued.

These dark elements of the cosmos have come to be known as dark energy, a mysterious force that causes the expansion of the universe to accelerate and accounts for around 70% of the universe's matter and energy budget and dark matter (the outstanding 25% of the universe's matter/energy budget) strange "stuff" that outweighs ordinary matter by 5 to 1 in the cosmos, but remains invisible because it doesn't interact with light.

"The whole purpose of Euclid is really to put those two together to understand the nature of dark matter and dark energy and how they're coupled in the universe," Mundell said. "Really, Euclid is not only a dark universe detective, it's also a time machine. We will look back 10 billion years in cosmic history."

Euclid visited 26 million galaxies in one week

For this first data release, Euclid, which launched in July 2023 and began observations proper in Feb. 2024, spent just one week scanning three patches of the sky over which it will make its deepest observations in the future.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Performing just one scan of each of these regions thus far, Euclid was able to observe 26 million galaxies, the furthest and thus earliest of which is around 10.5 billion light-years away. The observations also contain a small sample of quasars, the bright hearts of active galaxies powered by feeding supermassive black holes, which, because of their incredible luminosity, can be seen even further away.

While Euclid will pass over these patches many more times before its primary mission draws to a close in 2030, the first glimpse of these areas, about as wide in the sky as 300 full moons, provides an awe-inspiring preview of the sheer scale of the cosmic atlas that Euclid will build. By mission completion, this atlas will cover around one-third of the entire night sky over Earth.

The three deep fleids observed by Euclid are Euclid Deep Field North, Euclid Deep Field Fornax, and Euclid Deep Field South.

Below is the image Euclid captured of Euclid Deep Field North containing over 10 million galaxies, the Cat’s Eye Nebula (center-left), a stellar remnant around 3,000 light-years away, and a large group of galaxies dominated by the large galaxy NGC 6505 right of center). Euclid will make a total of 32 sweeps of this region of the sky before 2030.

The next image represents Euclid's first look at the region dubbed Euclid Deep Field Fornax, in which it has already seen 4.5 million galaxies. Over the next six years, Euclid will make 52 observations of this region of space.

Euclid Deep Field Fornax contains the smaller Chandra Deep Field South region which has been studied by NASA's Chandra and ESA's XMM-Newton X-ray observatories, in addition to the Hubble Space Telescope and major ground-based telescopes.

![On a black background lies an almost square shape with notches cut out of its corners, oriented with its upper and lower edges sloping slightly from top left to bottom right. Contained within the shape are 4.5 million galaxies, and stars of various size, brightness and colour. Some of the brighter stars have diffraction spikes.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/CtcsAdt8CRd8Vtd5kcYfzf.jpg)

Less well-studied is Euclid Deep Field South (below), which has not been assessed by any other deep sky survey thus far. That means this region, also Euclid's largest deep field, has a vast potential for new, exciting discoveries.

The space telescope has already spotted more than 11 million galaxies in this field. Additionally, in this field, Euclid observed hints at a large-scale structure of the universe called the cosmic web, consisting of threads of gas and dark matter stretching between clusters of galaxies.

"It's impressive how one observation of the deep field areas has already given us a wealth of data that can be used for a variety of purposes in astronomy: from galaxy shapes to strong lenses, clusters, and star formation, among others," ESA Euclid project scientist Valeria Pettorino said. "We will observe each deep field between 30 and 52 times over Euclid's six-year mission, each time improving the resolution of how we see those areas and the number of objects we manage to observe.

"Just think of the discoveries that await us."

Euclid's observations take shape

Because dark matter's mass dominates galaxies, it plays a vital role in galactic evolution and, ultimately, the shapes these galaxies take. That means in order to probe the mysteries of dark matter, Euclid precisely must precisely observe the shape or "morphology" of billions of galaxies.

Because galaxies come together in a web of dark matter, forming large galaxy clusters, Euclid can also learn more about this mysterious stuff by measuring the distribution of the millions of galaxies visible in each of its deep fields.

Likewise, this distribution is also important to understand how dark energy has expanded the fabric of space, thus pushing these galaxies apart.

"The full potential of Euclid to learn more about dark matter and dark energy from the large-scale structure of the cosmic web will be reached only when it has completed its entire survey," Euclid Consortium scientist Clotilde Laigle said. "Yet the volume of this first data release already offers us a unique first glance at the large-scale organization of galaxies, which we can use to learn more about galaxy formation over time."

The observations of these galaxies in this first release alone constituted 35 terabytes of data collected over one week.

"To give you a feeling that 35 terabytes of data are the equivalent of 200 days of video streaming at the highest quality," Pettorino said on Monday. "If you watch TV on your HDR, 4k with 60 frames per second for 200 days, then you would be that would be the equivalent of 35 terabytes."

The ESA project scientist added that next year, Euclid will release its first year of observations. This will be 2 petabytes of data, equal to streaming 31 years of 4K TV, Pettorino continued, advising against engaging in such a binge watch.

The stunning zoomed-in image of the Euclid Deep Field South below shows various galaxy clusters and the light between these galaxies, so-called "intracluster light." The image represents a 70-times zoom-in on the original mosaic, demonstrating why so much data is gobbled up in these Euclid images.

Euclid consortium member Mike Walmsley of the University of Toronto explained that no human could possibly hope to analyze all of this data, so scientists have turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to perform and initially filter this data, picking out galaxies for further investigation.

The galaxies the AI selects are then passed along to citizen scientists for them to identify aspects of these galaxies, such as their shape and brightness and characteristics like spiral arms, central bars, and tidal tails, the latter of which indicate merging galaxies.

"We're at a pivotal moment in terms of how we tackle large-scale surveys in astronomy. AI is a fundamental and necessary part of our process in order to fully exploit Euclid's vast dataset," Walmsley added. "We're building the tools as well as providing the measurements. In this way, we can deliver cutting-edge science in a matter of weeks, compared with the years-long process of analyzing big surveys like these in the past."

The Euclid consortium will need all the help it can get, the galaxies featured in the data released thus far represent just 0.4% of the total number of galaxies of similar resolution expected to be imaged over Euclid's lifetime.

"We're looking at galaxies from inside to out, from how their internal structures govern their evolution to how the external environment shapes their transformation over time," added Laigle. "Euclid is a goldmine of data, and its impact will be far-reaching, from galaxy evolution to the bigger-picture cosmology goals of the mission."

Uncovering gravitational lenses

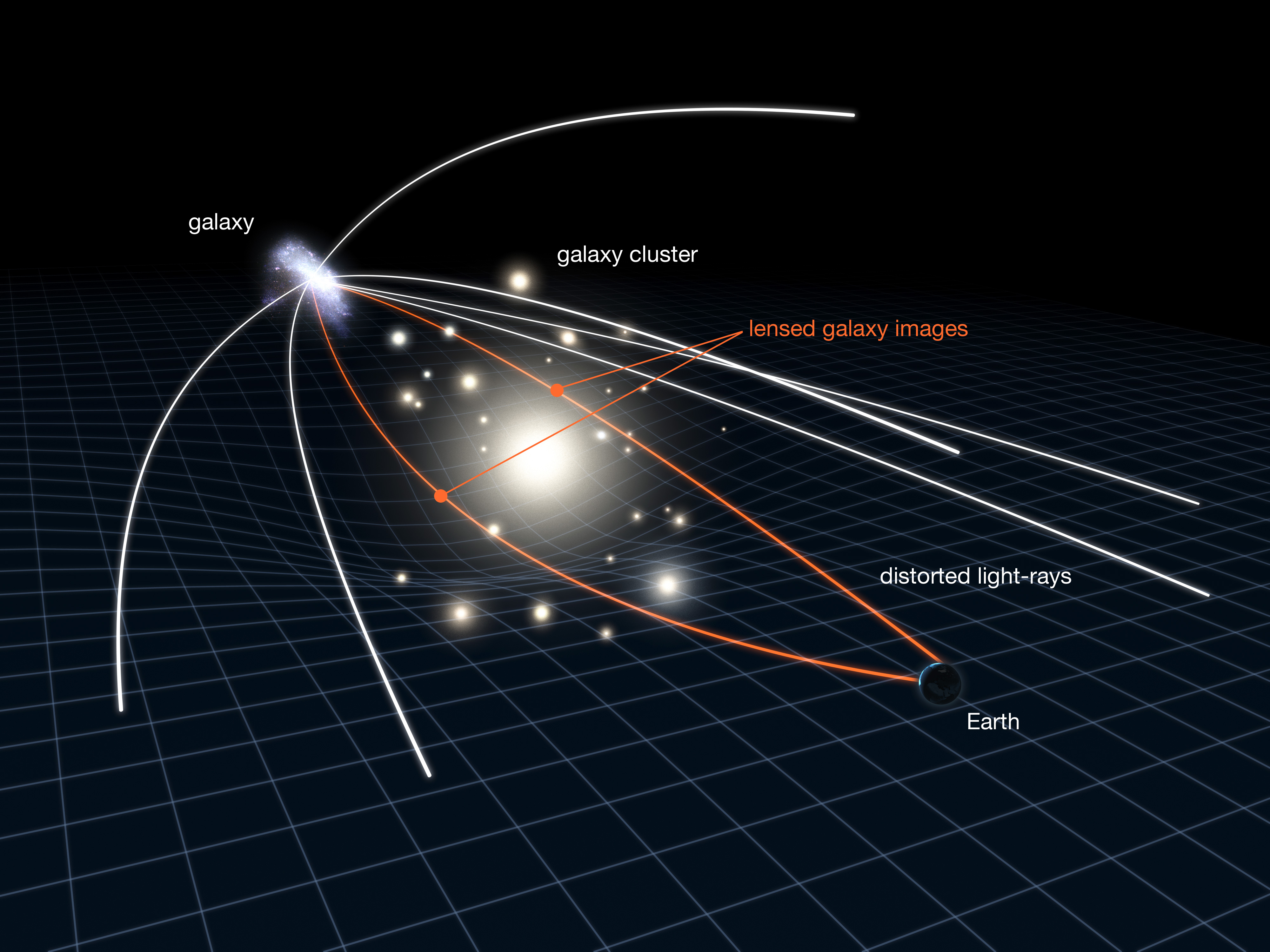

One of the most exciting aspects of this first Euclid data release is the revelation of extraordinary events in spacetime called "gravitational lenses." These distortions of distant objects occur when light from a background object passes a massive object, like a galaxy or galaxy cluster, that comes between it and Earth.

Because objects with mass cause the very fabric of space and time to warp (that's general relativity, folks) when light passes these intervening objects it is also curved. the closer to the body of mass, the gravitational lens, light passes, the more extreme its curvature.

That means that light from the same background object can reach Earth (or Euclid) at different times. This can either amplify these background objects— hence, the term "lensing"— or it can cause the same background object to appear distorted, stretched like taffy, or in multiple places in the same image, forming patterns like arcs or circles called "Einstein rings."

Euclid had already spotted a stunning Einstein ring, which was revealed to the public back in Feb. this year, but following the analysis of this new week's worth of data, AI and citizen scientists uncovered a further 500 examples of galaxy gravitational lenses amplifying light from a distant background galaxy. Lenses like this are rare because both the background galaxy and the lensing galaxy have to be perfectly aligned from Earth for this effect to work.

Almost all of these new Euclid gravitational lens arrangements were previously unknown.

"Until now, the vast majority of lenses have been found by ground-based telescopes. that is because lenses are so rare you need vast chunks of the sky to find them, and we simply haven't had a space telescope with the area and the resolution and the sensitivity to do that," Walmsley said. "Euclid is the first space telescope which can find a large number of lenses from space."

![A collage of fourteen by eight squares containing examples of gravitational lenses. Each example typically comprises a bright centre with smears of stars in an arc or multiple arcs around it as a result of light travelling towards Euclid from distant galaxies being bent and distorted by normal and dark matter in the foreground. In some rare cases the smearing is in a complete ring, creating a so-called Einstein Ring.]](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/ijpmpcm7BZET5RtWfHvTNJ.jpg)

By its release next year alone, Euclid is expected to have found 7,000 gravitational lens candidates. By the time its mission concludes in 2030, the Euclid consortium expects the dark universe detective spacecraft to have uncovered somewhere in the region of 100,000 galaxy-galaxy-strong lenses. That is around 100 times more strong gravitational lenses than is currently known.

Euclid will also be on the hunt for weakly lensed background galaxies with more subtle distortions. These distortions are too subtle to be seen in individual galaxies but can be detected when considering large samples of background sources. Weak lensing is key to investigating the warping of spacetime due to the distribution of invisible dark matter in lensing galaxies.

"This is a tiny taste of what's to come, but tiny is not the right word," Mundell concluded. "Scientists have a lot of work ahead of them in the next six years, but it's going to be phenomenally exciting and very, very interesting, groundbreaking work."

The three deep field preview from Euclid can now be explored in ESASky. Euclid Deep Field South is here, Euclid Deep Field Fornax: here and Euclid Deep Field North: here.

The 36 scientific papers that emerged from this first data drop from Euclid are available here.

And you fancy joining the 9976 citizen scientists of the GalaxyZoo, who helped classify the galaxies in Euclid's first deep field images, check out the Zooiverse website of the project here.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.