Large alien planets may be born in chaos, NASA's retired exoplanet-hunter finds

"There really is something very different about how these giant planets form versus how small planets like Earth form."

Scientists have used data from NASA's retired planet-hunting space telescope 'Kepler' to discover that small and large worlds have very different upbringings. The team found that larger planets on non-circular orbits are more likely to have grown in more turbulent home systems.

To reach this conclusion, the team studied the orbits of thousands of extrasolar planets, or "exoplanets." The team, consisting of researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), measured the orbits of exoplanets ranging in mass from that of Jupiter to that of Mars.

Smaller planets, it was revealed, tended to have nearly circular orbits, while larger giant planets have flattened, or elliptical, orbits. This would have been an important finding in isolation, but because scientists can tell a lot about a planet from its orbit, the discovery also reveals information about how planets of different sizes form.

"What we found is that right around the size of Neptune, planets go from being almost always on circular orbits to very often having elliptical orbits," team leader and UCLA researcher Gregory Gilbert said in a statement.

Eccentric large planets have chaotic upbringings

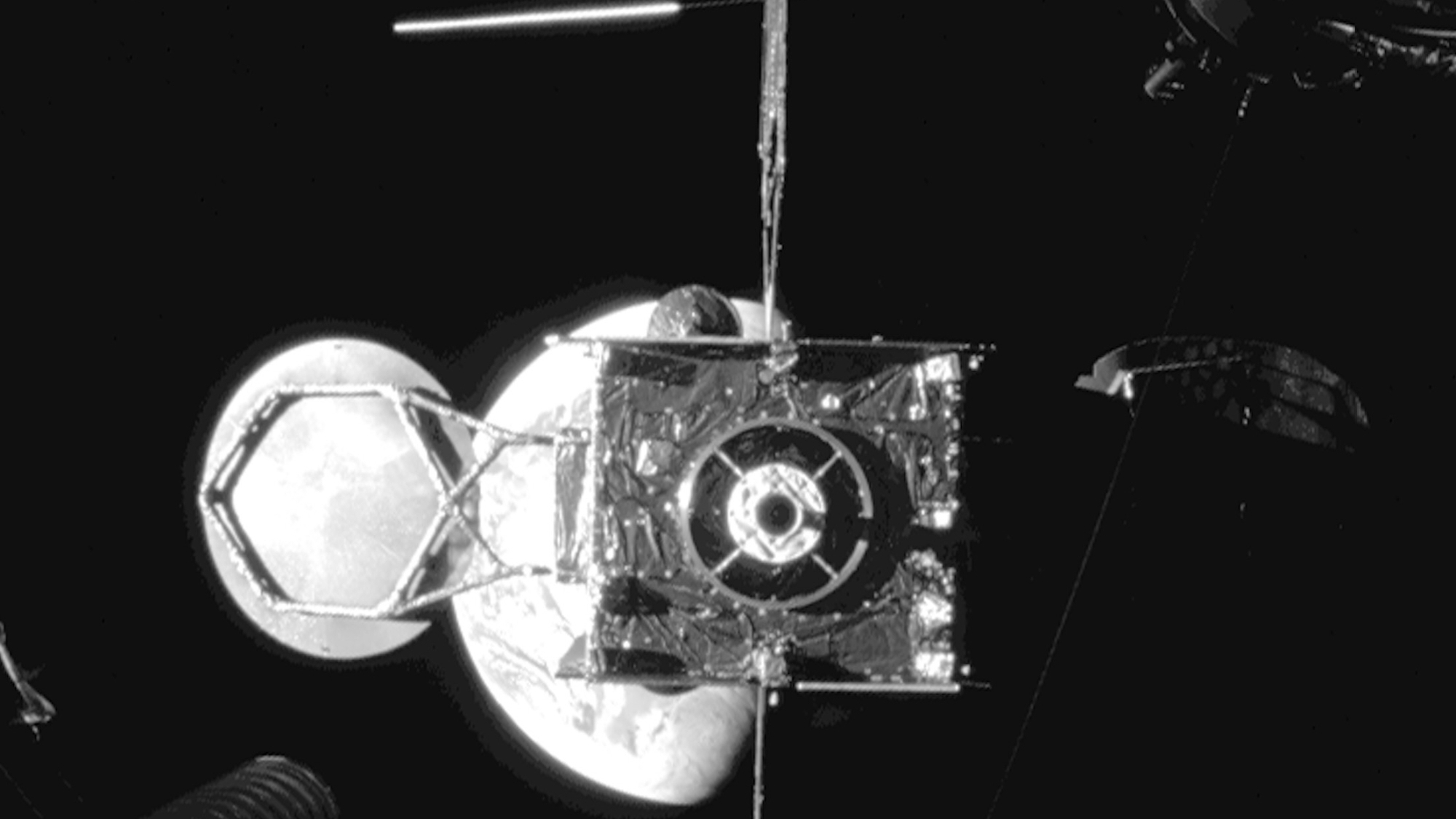

During its operating lifetime between 2009 and 2018, Kepler observed around 150,000 stars, looking for the tiny dips in light caused when a planet crosses, or "transits," the face of its star, as seen from our perspective in the cosmos.

Using this technique, and by gathering the light curves from these stars, Kepler uncovered thousands of exoplanets. The UCLA team turned to 1,600 of these light curves to extract information about the orbits of certain planets. This process required a great deal of care, the development of a custom visualization tool kit, and the manual inspection of each light curve by UCLA undergraduate Paige Entrica.

"If stars behaved like boring light bulbs, this project would have been 10 times easier," said team member Erik Petigura, a UCLA physics and astronomy professor. "But the fact is that each star and its collection of planets has its own individual quirks, and it was only after we got eyes on each one of these light curves that we trusted our results."

This meticulous analysis revealed the split between planets with circular orbits and those with more eccentric orbits.

There appeared to be an abundance of small planets over large planets and a tendency for giant planets to form around stars enriched in elements heavier than hydrogen and helium, such as oxygen, carbon and iron, which astronomers collectively call "metals."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Small planets are common; large planets are rare. Large planets need metal-rich stars in order to form; small planets do not," Gilbert explained. "Small planets have low eccentricities, and large planets have large eccentricities."

Seeing a correlation between the eccentricity of planetary orbits and the abundance of metals indicated to the team that there are two pathways of planet formation, one followed by large planets and one followed by small planets.

"To see a transition in the eccentricities of the orbits at this same point tells us there really is something very different about how these giant planets form versus how small planets like Earth form," Gilbert said. "That’s really the major discovery to come out of this paper."

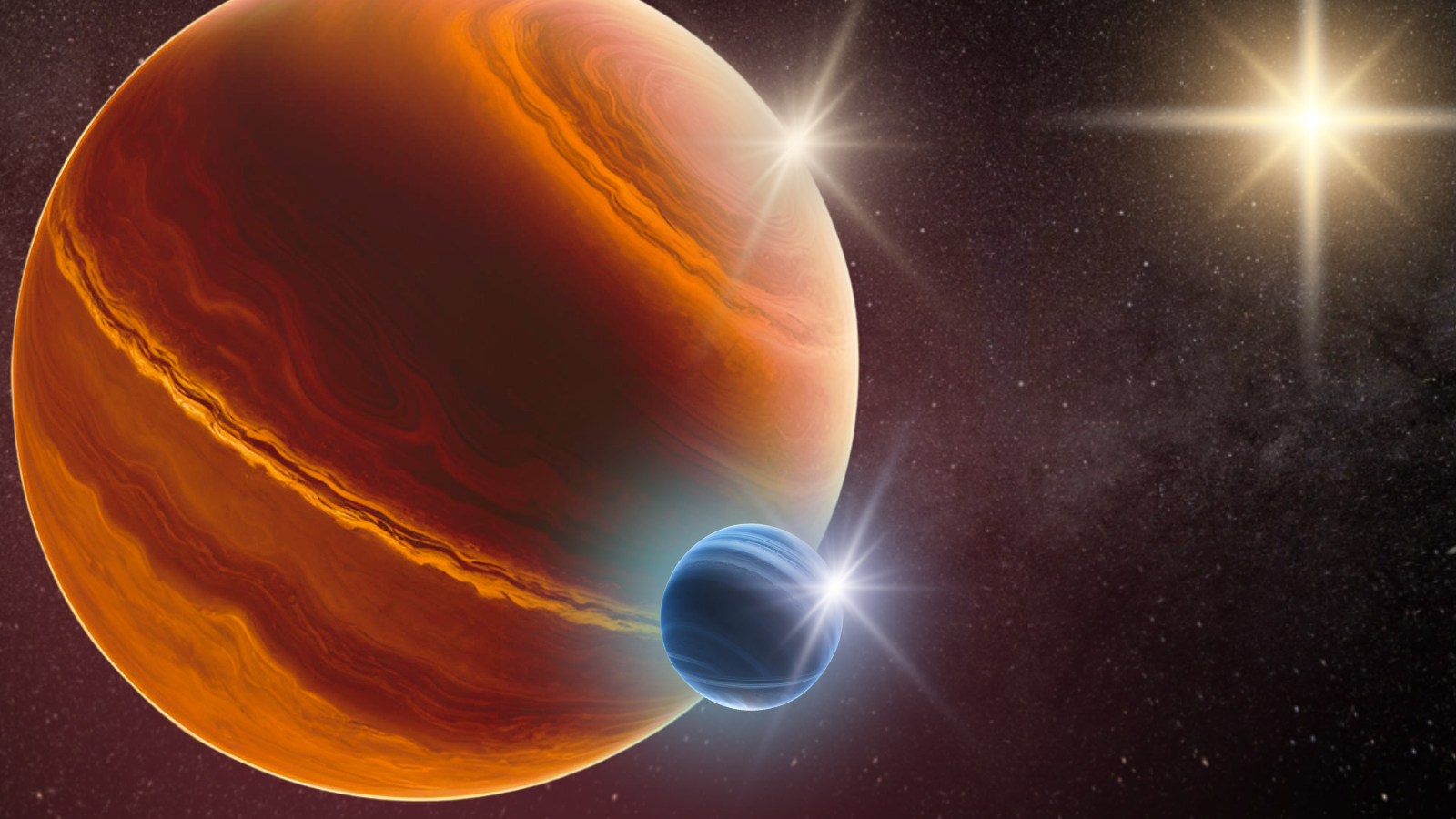

Currently, scientists theorize that planets are born in doughnut-shaped clouds of gas and dust called "protoplanetary disks." These protoplanetary disks surround infant stars, and give rise to worlds as larger and larger fragments within the disks meet and fuse.

This process could form a terrestrial planet around the size and mass of Earth — but if a large planetary core around 10 times the mass of our planet is formed, it can accumulate gas, creating a gas giant like Jupiter or Saturn.

Larger planets beyond the size of Neptune are thought to be fairly rare because it takes a rapid "runaway mass accretion" to accumulate a massive amount of gas. This happens more frequently around stars that are enriched with metals.

It is likely, the scientists suggest, that large planets on eccentric orbits may experience more chaotic formation processes as they gravitationally interact with their sibling planets to find themselves on non-circular orbits. These planets "stir up" their planetary systems, causing more turbulence. This results in collisions and mergers between planets larger than Earth, creating more large planets.

"It's remarkable what we've been able to learn about the orbits of planets around other stars using the Kepler Space Telescope," Petigura said. "The telescope was named after Johannes Kepler, who, four centuries ago, was the first scientist to appreciate that the planets in our solar system move on slightly elliptical rather than circular orbits. His discovery was an important moment in human history because it showed that the sun, rather than the Earth, was at the center of the solar system.

"I'm sure Kepler, the man, would be delighted to learn that a telescope named in his honor measured the subtle shapes of orbits of Earth-size planets around other stars."

The team's research was published on March 13 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.