How can Jupiter have no surface? A dive into a planet so big, it could swallow 1,000 Earths

Why does Jupiter look like it has a surface – even though it doesn’t have one? – Sejal, age 7, Bangalore, India

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Benjamin Roulston is Assistant Professor of Physics, Clarkson University

The planet Jupiter has no solid ground – no surface, like the grass or dirt you tread here on Earth. There’s nothing to walk on, and no place to land a spaceship.

But how can that be? If Jupiter doesn’t have a surface, what does it have? How can it hold together?

Even as a professor of physics who studies all kinds of unusual phenomena, I realize the concept of a world without a surface is difficult to fathom. Yet much about Jupiter remains a mystery, even as NASA’s robotic probe Juno begins its ninth year orbiting this strange planet.

First, some facts

Jupiter, the fifth planet from the Sun, is between Mars and Saturn. It’s the largest planet in the solar system, big enough for more than 1,000 Earths to fit inside, with room to spare.

Related: Jupiter: A guide to the largest planet in the solar system

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

While the four inner planets of the solar system – Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars – are all made of solid, rocky material, Jupiter is a gas giant with a composition similar to the Sun; it’s a roiling, stormy, wildly turbulent ball of gas. Some places on Jupiter have winds of more than 400 mph (about 640 kilometers per hour), about three times faster than a Category 5 hurricane on Earth.

Searching for solid ground

Start from the top of Earth’s atmosphere, go down about 60 miles (roughly 100 kilometers), and the air pressure continuously increases. Ultimately you hit Earth’s surface, either land or water.

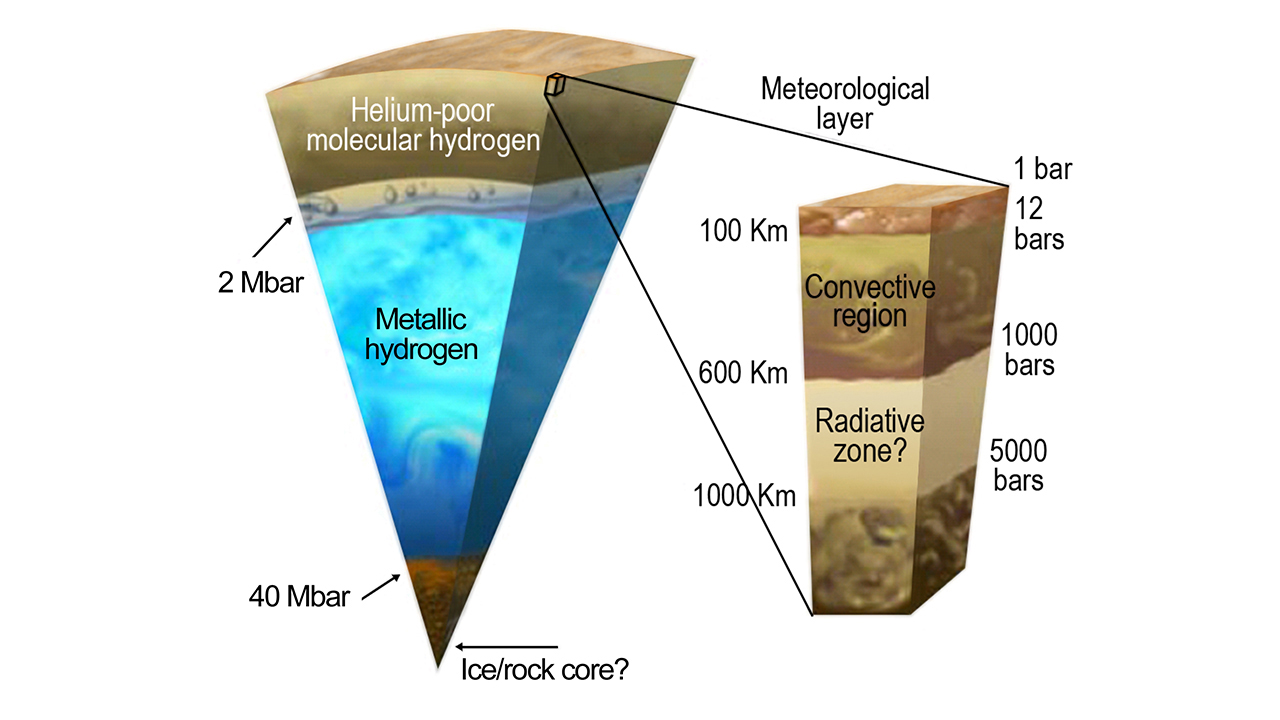

Compare that with Jupiter: Start near the top of its mostly hydrogen and helium atmosphere, and like on Earth, the pressure increases the deeper you go. But on Jupiter, the pressure is immense.

As the layers of gas above you push down more and more, it’s like being at the bottom of the ocean – but instead of water, you’re surrounded by gas. The pressure becomes so intense that the human body would implode; you would be squashed.

Go down 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers), and the hot, dense gas begins to behave strangely. Eventually, the gas turns into a form of liquid hydrogen, creating what can be thought of as the largest ocean in the solar system, albeit an ocean without water.

Go down another 20,000 miles (about 32,000 kilometers), and the hydrogen becomes more like flowing liquid metal, a material so exotic that only recently, and with great difficulty, have scientists reproduced it in the laboratory. The atoms in this liquid metallic hydrogen are squeezed so tightly that its electrons are free to roam.

Keep in mind that these layer transitions are gradual, not abrupt; the transition from normal hydrogen gas to liquid hydrogen and then to metallic hydrogen happens slowly and smoothly. At no point is there a sharp boundary, solid material or surface.

Scary to the core

Ultimately, you’d reach the core of Jupiter. This is the central region of Jupiter’s interior, and not to be confused with a surface.

Scientists are still debating the exact nature of the core’s material. The most favored model: It’s not solid, like rock, but more like a hot, dense and possibly metallic mixture of liquid and solid.

The pressure at Jupiter’s core is so immense that it would be like 100 million Earth atmospheres pressing down on you – or two Empire State buildings on top of each square inch of your body.

But pressure wouldn’t be your only problem. A spacecraft trying to reach Jupiter’s core would be melted by the extreme heat – 35,000 degrees Fahrenheit (20,000 degrees Celsius). That’s three times hotter than the surface of the Sun.

Jupiter helps Earth

Jupiter is a weird and forbidding place. But if Jupiter weren’t around, it’s possible human beings might not exist.

That’s because Jupiter acts as a shield for the inner planets of the solar system, including Earth. With its massive gravitational pull, Jupiter has altered the orbit of asteroids and comets for billions of years.

Without Jupiter’s intervention, some of that space debris could have crashed into Earth; if one had been a cataclysmic collision, it could have caused an extinction-level event. Just look at what happened to the dinosaurs.

Maybe Jupiter gave an assist to our existence, but the planet itself is extraordinarily inhospitable to life – at least, life as we know it.

The same is not the case with a Jupiter moon, Europa, perhaps our best chance to find life elsewhere in the solar system.

NASA’s Europa Clipper, a robotic probe launched in October 2024, is scheduled to do about 50 fly-bys over that moon to study its enormous underground ocean.

Could something be living in Europa’s water? Scientists won’t know for a while. Because of Jupiter’s distance from Earth, the probe won’t arrive until April 2030.

Dr. Benjamin Roulston is an Assistant Professor of Physics and the Director of the Observatory at Clarkson University in Potsdam, NY.

Since joining Clarkson University in 2023, Dr. Roulston has been dedicated to teaching and research, focusing his research on binary stars, specifically post-mass transfer binaries. His research investigates how binary stars can exchange mass and interact together, contributing to the understanding of various astrophysical processes such as common-envelope-evolution.

Dr. Roulston completed his PhD at Boston University while serving as a predoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. His doctoral research concentrated on binary stars, particularly dwarf carbon stars, utilizing models and observations from Chandra, Hubble, and various optical telescopes to study their formation and properties.

Before joining Clarkson University, he was a postdoctoral fellow at Caltech working on the Zwicky Transient Facility project. At Clarkson University, Dr. Roulston teaches a range of courses, including introductory physics (Physics 1 and 2), an introductory astronomy course, an advanced astrophysics course, and an aerospace engineering course on the space environment. His teaching philosophy emphasizes engaging students through problem-solving and hands-on experience with real data, bridging the gap between theoretical concepts and practical application.