Mars meteorite found in drawer reveals history of water on Red Planet

"We think the water came from the melting of nearby sub-surface ice called permafrost, and that the permafrost melting was caused by magmatic activity that still occurs periodically on Mars to the present day."

A meteorite from Mars has a history of interacting with water, probably as a result of volcanic activity melting ice on the Red Planet over 700 million years ago.

The findings help reveal the story of an 800-gram (1.8 pound) meteorite that has remained a mystery for nearly 100 years, having been found in a desk drawer at Purdue University in Indiana, USA, in 1931.

An international team of scientists led by Purdue’s Marissa Tremblay has the answers. By dating the water-altered minerals in the Lafayette meteorite, they zeroed in on a date of 742 million years ago. However, according to Mars climate science, the Red Planet’s liquid water mostly vanished over 3 billion years ago. So where did the water come from 742 million years ago?

The meteorite was named Lafayette, after the city in which Purdue University is based. How it came to be in that drawer was unknown, but what was known was that it had originally come from Mars and had once interacted with liquid water there. The question was, how long ago was its wet experience?

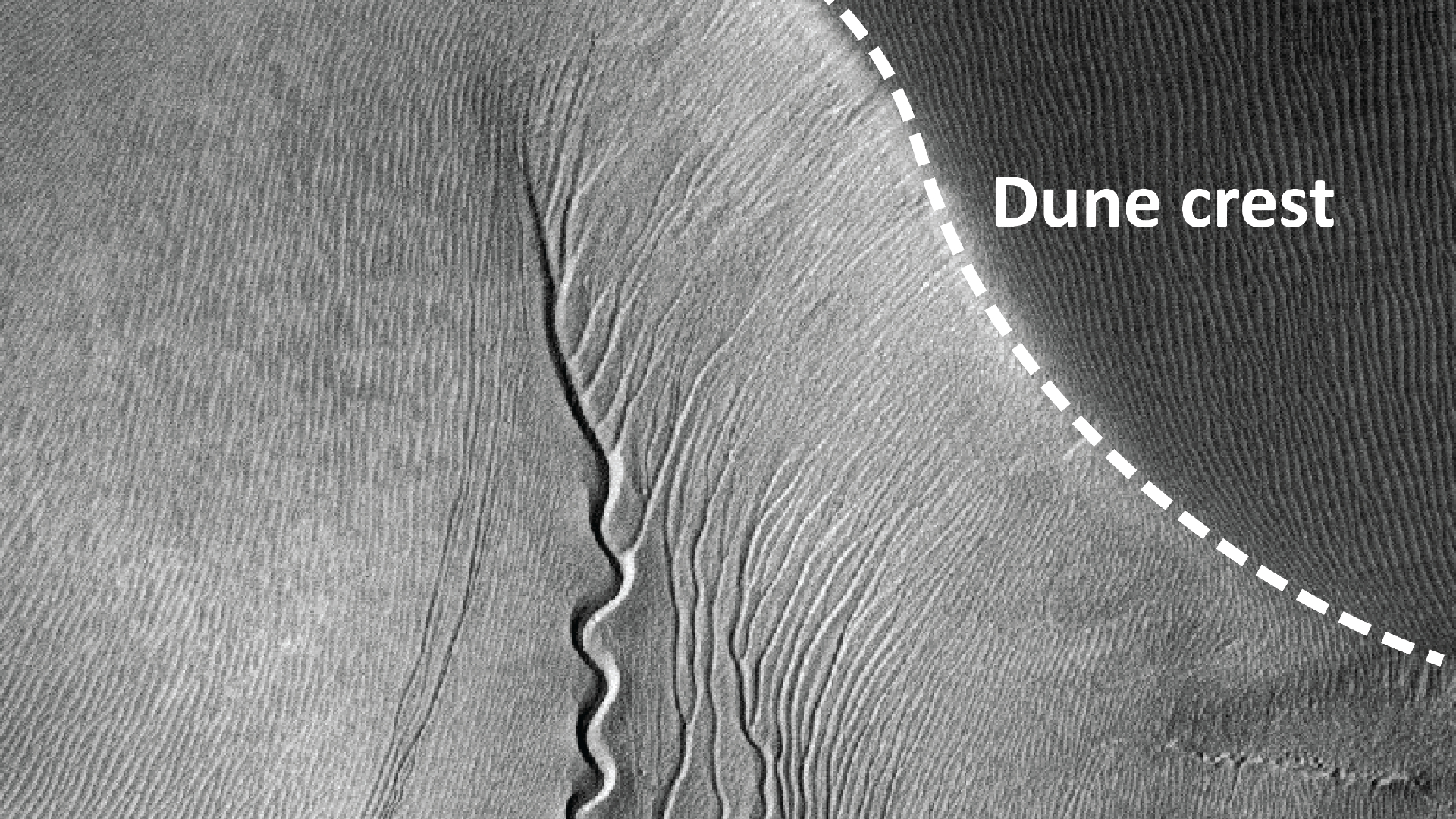

"We do not think there was abundant liquid water on the surface of Mars at this time," said Tremblay in a statement. "Instead, we think the water came from the melting of nearby sub-surface ice called permafrost, and that the permafrost melting was caused by magmatic activity that still occurs periodically on Mars to the present day."

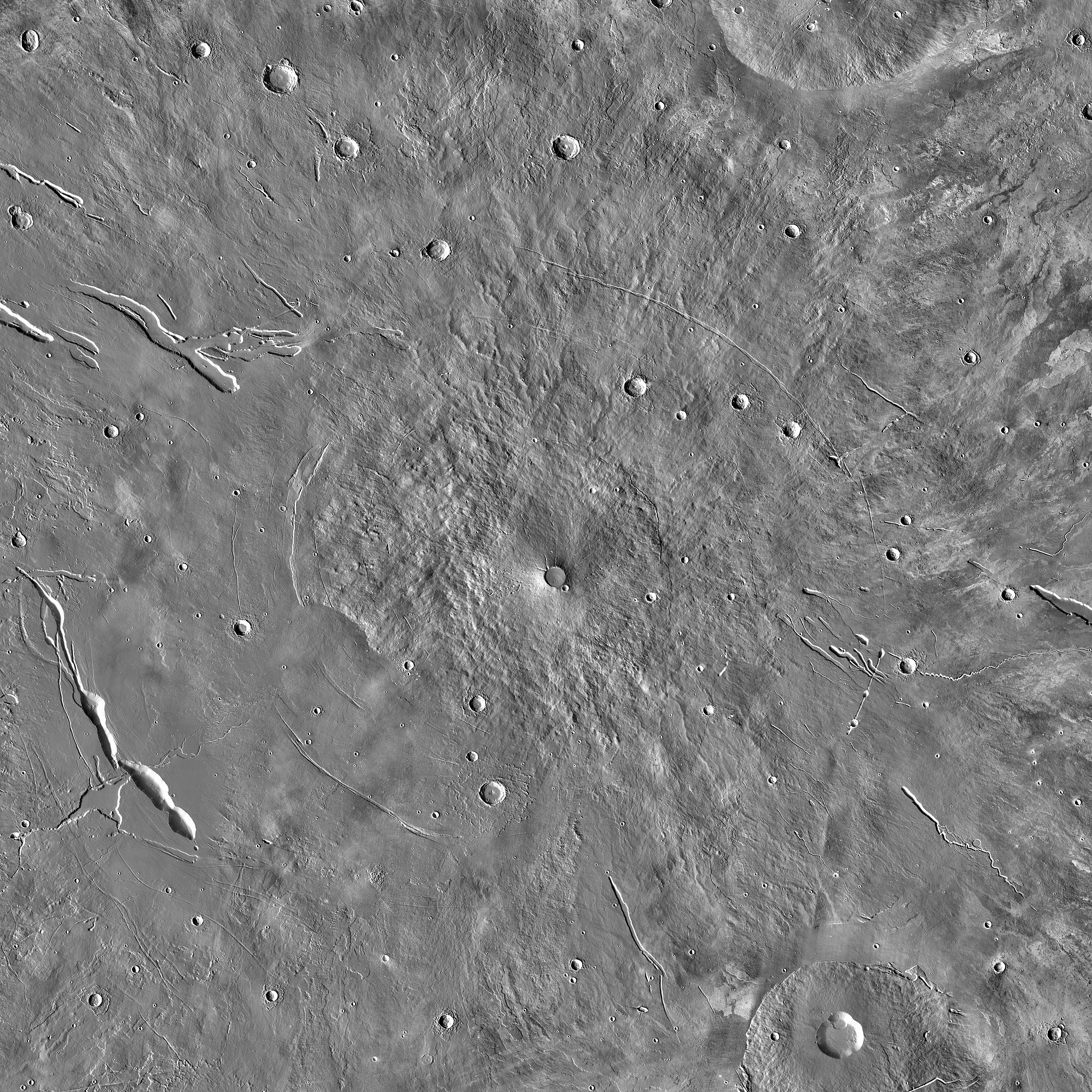

The Lafayette meteorite is a type of Martian meteorite known as a nakhlite. Made from igneous, i.e. volcanic, rocks, they possibly originate from a crater on the basaltic lava planes near the extinct Elysium Mons volcano. Therefore, chronicling the nakhlite’s history on Mars is a key aim of planetary scientists.

Once the Lafayette meteorite (and possibly the other nakhlites too) had been blasted off Mars by an impact and sent spinning into space, it was exposed to the cosmic rays that irradiated the meteorite, forming isotopes that have been dated to 11 million years ago, coinciding with the age of the crater near Elysium Mons.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But when did the Lafayette meteorite arrive on Earth, and how did it end up in that drawer?

In an earlier paper from 2022, researchers including Tremblay conducted some detective work to figure it out. They identified contamination from the mycotoxin deoxynivalenol, better known as vomitoxin, which is a disease that affects crops.

"We used organic contaminants from Earth found on Lafayette – specifically, crop diseases – that were particularly prevalent in certain years to narrow down when it might have fallen, and whether the meteorite fall may have been witnessed by someone," said Tremblay.

Tremblay and her colleagues concluded that Lafayette must have fallen in a field of crops somewhere in semi-rural Indiana in about 1919, where it was found by a Purdue University student who possibly saw it fall. They brought it back to the university, where it ended up in that drawer to be discovered 12 years later. The rest, as they say, is history.

The findings were published Nov. 6 in the journal Geochemical Perspective Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.